The test stand is tucked into a dry corner of the desert, where the wind smells faintly of sand and hot metal. It’s early—too early for the vultures that usually ride the thermals overhead—but the air already shivers with heat. On the concrete pad, a compact, oddly beautiful machine sits wired with sensors, pipes, and thick cables. A group of engineers and Air Force officers stand behind thick blast shields, eyes fixed on monitors. Someone gives a quiet countdown. Then the world changes.

The engine doesn’t roar in the way you expect. It snarls—sharp, staccato, like a drum roll made of thunder. The sand around the pad trembles. A tight, pale-blue ring of fire curls inside the engine’s open throat, spinning faster than the human eye can track. You can feel it more than see it: a vibration in your ribs, a low hum in your teeth. In that ring of fire lives the United States’ bet on the next generation of hypersonic missiles—small, fast, and terrifyingly efficient.

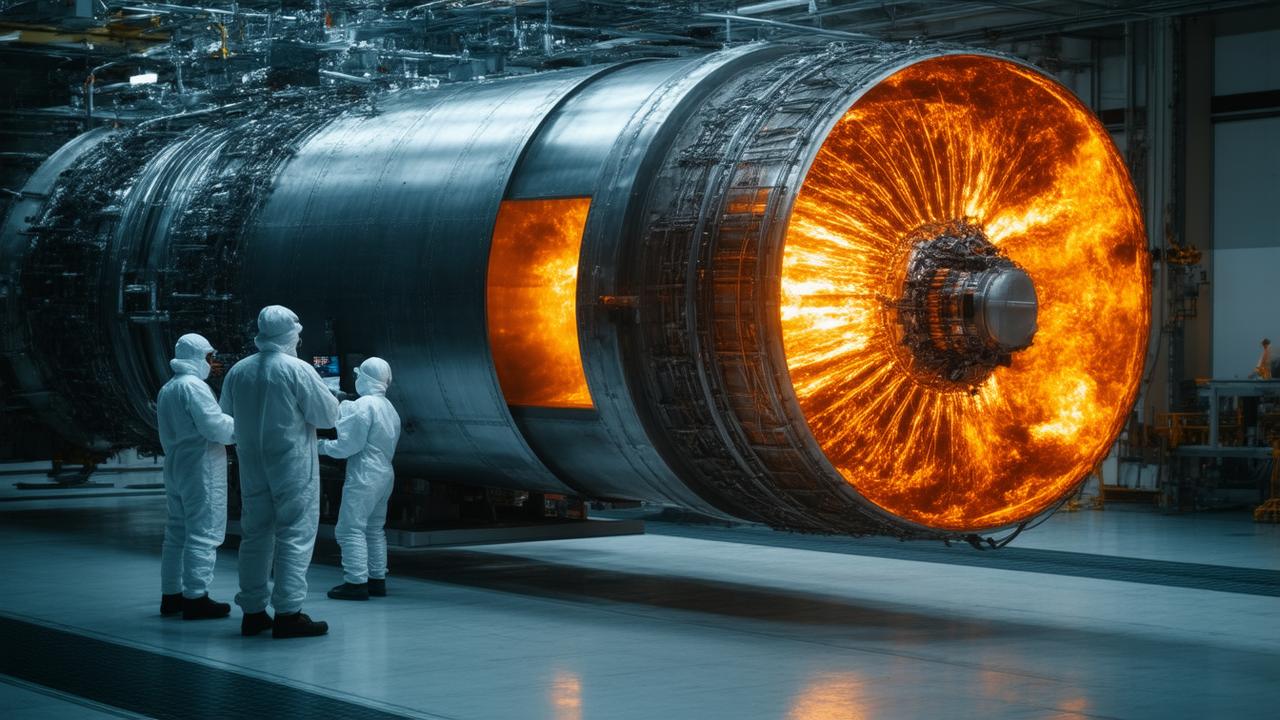

The Strange Beauty of a Spinning Explosion

For more than a century, we’ve burned fuel in engines the same basic way: mix air and fuel, ignite, push something forward. Jet engines compress air, add fuel, burn it, and throw the hot gases out the back; rockets do their own variation of the same dance. It’s violent, but it’s steady violence—a smooth burn, controlled and continuous.

Rotating detonation engines, or RDEs, are not interested in being smooth.

Inside an RDE, combustion happens as a continuous series of detonations racing in circles. Imagine a narrow ring-shaped chamber, like a hollow metal donut. Fuel and oxidizer are injected at one end of this circular channel, and then—once lit—a shockwave of flame chases itself around and around the loop, detonating fresh mixture as it goes. Instead of one big boom followed by exhaust, or one long steady burn, the engine operates on blisteringly fast, self-sustaining shockwaves.

From a distance—and through heavy protective glass—it’s mesmerizing. That dancing ring of flame is not just energy; it’s order laid over chaos. The U.S. is now pushing hard to tame this chaos, investing in RDE technology to power its next generation of hypersonic missiles. The promise is simple to state and brutally hard to deliver: more reliable, smaller, faster weapons that work in the harshest, strangest parts of the atmosphere.

The Hypersonic Problem the U.S. Is Trying to Solve

Hypersonic flight, in simple terms, is anything above Mach 5—five times the speed of sound. At those speeds, air behaves less like a soft fluid and more like a sandblaster made of gas. Temperatures spike. Surfaces glow. The thin boundary layer of air that usually hugs an aircraft’s skin becomes hysterical, shedding shocks and plasma.

The United States wants missiles that can cut through this environment reliably, again and again, under combat conditions. That means:

- Engines that can start and stay lit in ultra-thin, high-speed airflow

- Propulsion systems that don’t guzzle so much fuel they become too heavy

- Hardware that can survive thermal torture without melting or cracking

- Guidance systems that don’t get confused while riding a fireball

Traditional rocket and air‑breathing engines can do some of this, but they bump against hard limits of weight, complexity, and efficiency. Hypersonic boost-glide vehicles and scramjets—two of the United States’ main hypersonic paths—have made impressive strides, but they still wrestle with reliability and range. That’s where RDEs enter the picture.

The Pentagon, through agencies like DARPA, the Air Force Research Laboratory, and the Navy, has been quietly channeling funds into RDE research. In labs from Ohio to California, teams test small, brutal-looking metal rings that howl when they run, hoping to extract just a little more stability, a little more predictability, out of spinning detonations.

Why Rotating Detonation Engines Might Change the Game

On the surface, an RDE looks like a step backward—who decides that more explosions per second is the strategy for reliability? But at hypersonic speeds, the physics of combustion shifts in surprising ways. Detonations can be more efficient than traditional combustion.

In a normal engine, burning fuel builds pressure over time. In a detonation, a shockwave compresses the fuel-air mixture first, then it detonates—a sharp spike of pressure and temperature that can extract more useful work from the same amount of propellant. That’s the secret: more energy for less mass.

For hypersonic missiles, engineers are chasing a few key advantages:

- Higher efficiency: RDEs can theoretically get more thrust per unit of fuel than conventional combustors.

- Smaller engines: With more energy packed into a compact geometry, hypersonic vehicles can carry more payload or fly farther.

- Simpler architecture: The rotating detonation can potentially replace bulky combustion chambers and complex staging hardware.

- Better performance at extreme conditions: Detonations can remain stable even as airflow and pressures swing wildly during hypersonic flight.

Reliability, paradoxically, might come from embracing something that looks inherently unstable—but is, after enough testing, remarkably repeatable. Once the detonation wave is established inside that ring, it tends to lock in, circling hundreds of thousands of times per second in a steady, humming fury.

For the missile, that could mean fewer moving parts, fewer failure points, more predictable performance. For planners in Washington, it could mean having a weapon that doesn’t just work on a good day, under test conditions—but on the worst day, with the wind wrong and the stakes high.

Inside the Test Cell: Where Theory Meets Heat

Walk into a government propulsion lab when an RDE test is about to happen and the air is all coffee and quiet tension. There’s a sense that something genuinely new is trying to be born. The engine itself is almost disappointingly small: a short cylinder wrapped in wires, cooling lines, and sheets of thermal insulation. You’d expect something that sounds like the end of the world to be bigger.

On the screens in front of the operators, however, the engine is larger than life. Pressure sensors, temperature gauges, high-speed cameras—all stitched into multicolored graphs. You watch as fuel valves open. Chill lines turn warm. The countdown begins.

When the engine fires, the numbers spike. In microseconds, the detonation wave forms and begins its endless sprint around the ring. Researchers are hunting for specific signatures: a stable frequency of the detonation wave, clean pressure patterns, no strange oscillations that could grow into catastrophic vibrations. Every data point feeds into simulations that chew on equations too complex for intuition.

At the far end of this chain of effort is a missile—sleek, dark, silent until launch. You can imagine it riding the edge of the atmosphere, the sky outside the nose cone more violet than blue, plasma licking at its flanks. Deep inside, the RDE is spinning fire in tidy circles, eating fuel in sharp, efficient bites, pushing the missile at speeds that erase distance and compress decision time.

It’s a haunting thought: human decisions about power, conflict, and deterrence being carried at Mach 6, Mach 8, Mach 10, on the back of a ring of controlled detonations.

How RDEs Stack Up for Hypersonic Missions

To understand what the United States is buying with its investment, it helps to compare rotating detonation engines with more traditional propulsion options often discussed for hypersonic use.

| Feature | Traditional Rocket / Ramjet | Rotating Detonation Engine |

|---|---|---|

| Combustion Type | Deflagration (subsonic burn) | Detonation (supersonic shockwave) |

| Efficiency Potential | Good but limited by combustion losses | Higher theoretical specific impulse |

| Engine Size / Weight | Larger chambers, more structure | More compact for same thrust |

| Operating Complexity | Well understood, but bulky | New control challenges, fewer moving parts |

| Suitability for Hypersonic Missiles | Proven but with range/weight tradeoffs | Promising for longer range and compact designs |

A Quieter Race in a Loud World

The geopolitics around hypersonic weapons are feverishly loud—headlines about “unstoppable” missiles, new arms races, shifting balances of power. But the work that actually makes these systems real is quiet. It takes place in windowless control rooms, in the clatter of machine shops, in long nights spent debugging simulations that crash at 99% completion.

The United States’ investment in rotating detonation technology is partly reactive. Other major powers are sprinting toward hypersonic capabilities, and every country that joins the race pulls the others along. But it’s also a continuation of a particular American habit: taking a wild-sounding piece of physics and hammering it into something operational.

There’s an uneasy duality here. The same RDE concepts that might one day power hypersonic missiles could, in a more hopeful future, drive highly efficient launch systems, reusable spaceplanes, or compact power units for deep-space missions. The boundary between destructive and exploratory technologies is thin, often defined less by metal and flame than by policy and intention.

➡️ 3 Primary Health Benefits of Consuming Ginger Juice

➡️ The Tank Water Heater’s Sediment Build-Up Robs Efficiency And Mimics The Sound Of A Failing Appliance

➡️ An Effective Drain Cleaning Method Without Vinegar or Baking Soda

➡️ A rare giant bluefin tuna is officially measured and confirmed by marine biologists adhering to strict peer-reviewed protocols

➡️ After 60, quitting these nine habits can dramatically improve happiness

➡️ From February 8, pensions will rise only for retirees who submit a missing certificate, triggering anger among those without internet access

➡️ While digging a home swimming pool, a French homeowner unearthed a cache of gold bars valued at €700,000, creating a legal quandary

Inside the Pentagon, RDEs are largely discussed in the language of deterrence and survivability. If adversaries field maneuverable hypersonic weapons that can evade traditional defenses, the thinking goes, the U.S. must respond in kind—or fall behind. Reliability becomes not just a matter of engineering, but of credibility. Does a rival believe that, if pushed, your high-end systems will actually work?

From Fire Ring to Flight Line

Turning a working lab engine into a combat-ready missile propulsion system is where the romance of the technology collides with the grind of reality. RDEs must:

- Operate across a wide range of altitudes and Mach numbers

- Integrate with fuel systems that are safe, stable, and storable

- Survive rapid thermal cycling—cold storage, then sudden ignition

- Play nicely with guidance electronics that hate vibration and heat

Every piece of that puzzle demands testing: on the ground, in wind tunnels, strapped under aircraft wings, and eventually in real flights that splash into distant seas. Failures will happen. Engines will misfire. Parts will melt. Somewhere, a quiet conference room will host a tense meeting about why an expensive test round tumbled instead of gliding.

But progress has a particular sound in propulsion work: the shift from a ragged, sputtering burn to a clean, predictable tone. Engineers talk about “getting good data,” which usually means the engine behaved itself long enough for instruments to make sense of it. As that data accumulates, designs change, materials improve, control software gets smarter. The strange fire ring edge closer to operational maturity.

If and when the first operational U.S. hypersonic missile powered by an RDE is fielded, it will carry inside its skin a lineage of thousands of such tests—each one a conversation between idea and reality. Each one a small bet that spinning detonations can be not just spectacular, but dependable.

Standing in the Shockwave’s Shadow

Back at the desert test stand, the engine winds down. The ring of fire shudders, flickers, and finally goes dark. The air cools from searing to merely hot. Technicians move carefully around the hardware, heat shimmer still rising from the metal like a mirage. It looks, suddenly, very ordinary—a cylinder of steel and nickel, streaked with soot.

But the data recorded during that brief run will spend months alive on screens and servers. Somewhere in those numbers might be the first clear proof that a particular design is ready to leave the test stand and reach for the sky; or the painful evidence that it’s not.

The United States’ investment in rotating detonation engines is, at its core, an investment in mastering a specific kind of violence—transforming chaotic shockwaves into usable, predictable thrust. It’s a bet that reliability can be engineered from something as wild as a supersonic ring of fire, and that doing so will secure an edge in a race that very few people will ever directly see, but that could shape the balance of power for decades.

In a world of abstract strategies and satellite imagery, that engine on the pad is something disarmingly concrete: hot metal, loud sound, burned fuel. You can stand a safe distance away, feel the shock in your bones, and know that the future of hypersonic flight is being written not in slogans, but in the physics of how fire moves.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a rotating detonation engine in simple terms?

A rotating detonation engine is a type of engine where fuel and oxidizer burn in a ring-shaped chamber as a continuous spinning explosion, or detonation. Instead of a smooth flame, it uses a shockwave of combustion that travels around the chamber at supersonic speed, creating thrust more efficiently than traditional engines.

Why is the United States investing in this technology?

The U.S. is investing in RDEs because they may offer higher efficiency, smaller engine size, and better performance at extreme conditions compared to conventional propulsion. For hypersonic missiles, that can translate into longer range, more compact designs, and potentially more reliable operation in the harsh environment of high-speed flight.

How do RDEs improve the reliability of hypersonic missiles?

RDEs promise reliability by simplifying certain parts of the propulsion system and using a combustion process that can remain stable under extreme pressures and temperatures. Once the detonation wave is established in the chamber, it tends to be self-sustaining and predictable, which is valuable in the demanding conditions hypersonic missiles face.

Are rotating detonation engines only for weapons?

No. While current investment and urgency are strongly linked to military applications, the underlying technology could also be used in space launch systems, advanced aircraft, or potentially even high-efficiency power generation systems. The same physics that make RDEs attractive for missiles could be applied to more peaceful uses in the future.

How close are we to seeing RDE-powered hypersonic missiles in service?

Publicly available information suggests that RDEs are still in advanced research and early prototype stages. Ground tests have shown promising results, but turning these engines into fully integrated, flight-ready systems requires solving challenges in materials, controls, and system integration. They are not yet standard in operational missiles, but investment and testing are accelerating.