The first warning wasn’t a press release or a breathless news alert, but a feeling—small, electric, and strangely ancient—that something enormous was quietly rolling toward us through the calendar. It lurked behind everyday errands and weather reports, behind the hum of traffic and the blue glow of our screens: a shadow the size of a continent, moving with the slow certainty of clockwork and myth. People began to say it out loud in line at coffee shops, in hospital corridors, on late-night radio shows. The eclipse. Six full minutes of day turned to twilight. Six minutes in which millions of people would look up, hold their breath, and wait to see what the sky would do to them.

The Long Shadow

On paper, it looks simple. Astronomers—in love with angles and orbits—have drawn the path of totality like a bruise across the map. A narrow band, just a few hundred kilometers wide, slicing across cities, farmland, deserts, small towns with names no one outside the county has ever pronounced correctly. Within that path, for a window of time no longer than a pop song, the moon will slide perfectly between Earth and sun, damming the river of light that feeds our days.

But the numbers don’t quite capture what’s coming. They don’t tell you how the air will feel just before totality, or how birds will suddenly go silent as if someone has pressed pause on the world. They don’t describe the way colors will drain from the landscape, how green will flatten to charcoal, how faces will look dim and unfamiliar in the half-light. Astronomers call it “the eclipse of the century” for its rare length—up to six minutes and twelve seconds of total darkness in some places. That is an eternity, if you measure time in heartbeats.

In living rooms and news studios, a different kind of countdown has begun. Scientists argue over risks and reassurances. Public health officials issue calm, carefully worded statements. On message boards and in church basements, religious leaders warn of omens, of prophecy, of a world tipping toward judgment or renewal. Between the calculations and the prayers stands everyone else, wondering what to believe—and how worried, or hopeful, they ought to feel when the sky itself winks out.

When Daylight Breaks

On the outskirts of the city, in a pale building that smells faintly of antiseptic and coffee, Dr. Lila Mendoza pulls down a projection screen and clicks to the next slide. In front of her, a small army of nurses, school administrators, and local reporters stare back, pens poised. On the slide, an image of the sun’s blazing disk is overlaid with a black coin: the moon. Around its edge, the corona flares like white fire.

“The biggest risk,” she says, tapping the screen with the side of her hand, “is your eyes. It always has been.” Her voice is steady, practiced, shaped by weeks of interviews. “If you look directly at the sun without proper protection—even during a partial eclipse—you can burn your retinas. You won’t feel it. There are no pain receptors there. You may not know until hours later, when the damage is done.”

This is the ground most scientists agree on. There is strong consensus about the danger of staring at the sun; “ocular burns,” “eclipse blindness,” and “solar retinopathy” are phrases that have invaded nightly newscasts. Special eclipse glasses, properly certified and filtered, have become talismans, traded and hoarded like concert tickets. Schools debate whether to keep children indoors or march them out in supervised wonder.

But beyond the eyes, the conversation grows less tidy. In one camp are those who insist that, aside from vision, the eclipse poses no unique physical threat. “It’s just a shadow,” they say. Cosmic geometry, nothing more. The sun’s radiation isn’t fundamentally different on that day; it’s merely blocked for a short time. The gravitational tug is routine; the moon orbits us every 27 days regardless of our attention. To them, the eclipse is a spectacular, benign coincidence: the moon at just the right distance to cover the sun almost perfectly, a piece of celestial stagecraft we’re lucky to witness.

In the other camp, a smaller but louder chorus of researchers points to subtler possibilities. What about fragile circadian rhythms jolted by midday darkness? Could six minutes of abrupt night in the middle of a bright afternoon nudge hormonal cycles, upset sleep for days afterward, spike anxiety in those already prone to it? Could wildlife disturbances cascade into human spaces—panicked flocks in flight, disoriented insects, restless livestock? The data, they admit, are thin and patchy, drawn from eclipses that lasted far shorter than this one will.

Scientists at Odds

Behind closed doors and in very public panel discussions, the debate has become almost philosophical. At a planetary health symposium, a neuroscientist shows fMRI images of brains reacting to sudden darkness. “Look at the amygdala activation,” she urges. “This isn’t just about fear. It’s about unpredictability, about our wiring for threat detection when the environment behaves strangely.” Across the table, an epidemiologist counters that anxiety spikes whenever the news cycle is saturated with doom; the eclipse, she argues, may be less harmful than the stories we tell about it.

They talk about past eclipses: the one in 1999 that dimmed Europe, and the 2017 event that cut a luminous scar across the United States. Hospitals reported no mass wave of fainting or psychosis. ERs did not overflow with eclipse-specific emergencies beyond the occasional eye injury and traffic accident. If cosmic events were going to unravel us, they have mostly failed to do so.

Still, the “eclipse of the century” feels different. Its path crosses dense pockets of population, megacities already buzzing with stress and thin margins. Social media will make it omnipresent. Every second of darkness will be photographed, streamed, magnified, slowed down and replayed. Anticipation, some suggest, may be more potent than the shadow itself. If millions expect chaos, what kind of self-fulfilling choreography might unfold?

“The real health question,” one public health psychologist says, “is not ‘What will the eclipse do to us?’ but ‘What will we do to ourselves while we’re waiting for it?’” She describes elevated heart rates in people tracking disaster countdowns, the way chronic worry corrodes sleep and immunity. “A sky turning dark for six minutes is unlikely to break us. Weeks of fearful speculation might.”

Faith, Fear, and the Sky

Far from the sterile conference halls, in a converted warehouse lit by flickering candles, the mood is very different. Pastor Elijah Price stands at a lectern built from reclaimed wood and stares at a crowd of several hundred. Some have traveled for hours to be here. Outside, the streets are lined with cars bearing out-of-state plates, their dashboards cluttered with printed prophecies and hand-drawn maps of the eclipse path.

“We are told,” he says, voice rising and falling like a tide, “that the sun will be darkened and the moon will not give its light. We are told that signs will appear in the heavens.” His flock murmurs in agreement. For them, this eclipse is not an astronomical quirk but a whispered message from the divine, a hinge in history where something will shift decisively, for better or worse.

Religious groups—not just Christian congregations, but New Age circles, apocalyptic sects, and syncretic spiritual movements—are building elaborate narratives around the coming shadow. Some prepare with fasting and vigil, kneeling through the slow crawl of the moon as if awaiting a verdict. Others talk of portals opening, veils thinning, a rare chance for direct communion with whatever they believe sits beyond the sky. A smaller, more anxious subset warns of chaos: of civil unrest ignited by cosmic dread, of governmental collapse, of the fragile net of society snapping in those six dark minutes.

On social channels, rumors metastasize. Predictions of power grid failure, of satellites overwhelmed, of “cosmic radiation spikes” with no basis in physics. A viral voice-note claims hospitals have been told to stockpile body bags. Another says that governments planned the eclipse as an experiment on the population. The sun, in these stories, is no longer a star but a character in a soap opera of conspiracies.

And yet, under all the noise, there is something quieter: an almost shy longing. A desire for meaning in the face of a celestial event that does not need us at all. The sky, indifferent and precise, will carry on whether we tremble or celebrate. For many, the thought that such grandeur could be random and cold is unbearable. So they weave reasons into the darkness, like lanterns hung in an empty room.

Preparing for Six Minutes

Meanwhile, practical preparations unfold with a certain matter-of-fact tenderness. City councils meet to discuss crowd control and portable toilets. Police chiefs coordinate with transportation planners as if readying for a championship parade. Hospitals review staffing schedules and stock extra saline and bandages, not for metaphysical injuries but for the mundane hazards of people staring upward and stepping into curbs, of highways jammed with eclipse chasers.

In one small town near the centerline, the local librarian has become an unlikely logistics captain. Her quiet building, with its creaking floors and sun-faded posters, has been repurposed into an “eclipse hub.” She has boxes of certified solar glasses stacked beside the mystery novels. A hand-lettered sign reads: “FREE, ONE PER PERSON, PLEASE SAVE YOUR EYES.” She gives short talks on how to view the event safely, slipping in little bits of wonder between the safety warnings—how ancient astronomers used eclipses to understand the shape of our planet, how some cultures once banged pots and pans to scare away the dragon they believed was eating the sun.

Local hotels are booked solid. Farmhouses list spare rooms. A field on the edge of town, usually devoted to hay bales and quiet cows, is being transformed into an impromptu campground. Food trucks apply for permits to line the road leading to the best viewing hill. The town’s economy, usually sleepy and seasonal, thrums with possibility.

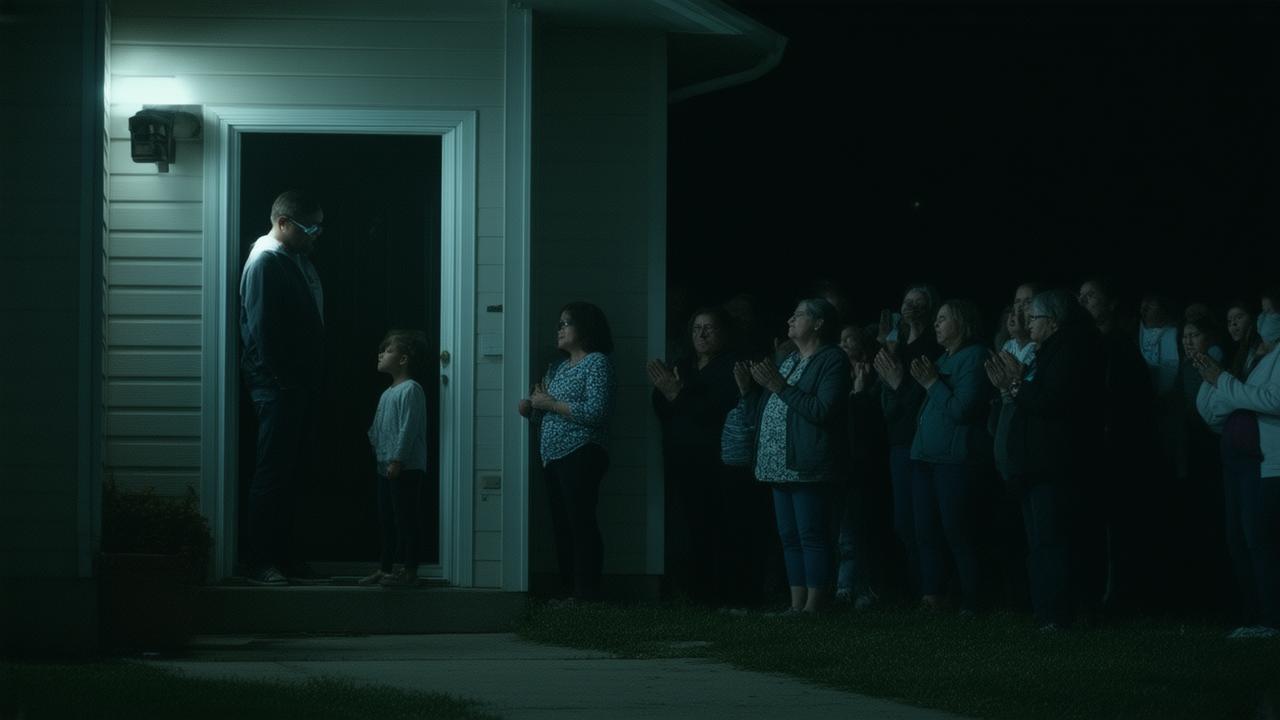

For families inside and outside the path of totality, calendars bear small circles around the date. Teachers prepare lesson plans tying together astronomy, history, and art. Parents debate whether to keep children close or let them experience the strangeness among friends at school. Somewhere, a teenager rehearses a proposal timed to the moment the corona flares to life. Somewhere else, someone quietly decides that this will be the day they finally tell the truth to someone they love. Cosmic spectacles have a way of making human secrets feel heavy and urgent.

| Aspect | Key Details |

|---|---|

| Maximum duration of totality | Approximately 6 minutes 12 seconds in select locations |

| Primary health concern | Solar eye damage from looking directly at the sun without proper protection |

| Other debated risks | Short-term anxiety, sleep disruption, traffic accidents, crowd-related stress |

| Community responses | Public viewing events, emergency planning, religious vigils, spiritual gatherings |

| Recommended protection | Certified eclipse glasses, indirect viewing methods, brief direct viewing only during full totality |

The Moment the World Holds Its Breath

On the day itself, morning will begin as any other. Coffee will steam in chipped mugs. Dogs will nose at leashes. Somewhere far from the path of totality, someone will forget entirely what date it is and go about their errands under an ordinary, unapologetic sun.

But inside that narrow band drawn on so many maps, the air will slowly begin to change. As the moon starts to bite into the sun, crescent shadows will appear under trees, the spaces between leaves acting like a thousand pinhole cameras. The light will grow weird, drained of its usual warmth, as if someone has turned down the saturation on the world. People will tilt their glasses upward in brief, cautious peeks, witnessing a star being eaten from the edge inward.

➡️ Half a glass and a toilet bowl like new: smart ways to restore old sanitary ware

➡️ Many people don’t realize it, but sweet potatoes and regular potatoes aren’t closely related at all “here’s why”

➡️ 9 things you should still be doing at 70 if you want people to one day say, “I hope I’m like that when I’m older”

➡️ A rare giant bluefin tuna is measured and confirmed by marine biologists using peer-reviewed protocols

➡️ A state pension cut is now approved with a monthly reduction of 140 pounds starting in February

➡️ A simple pantry powder rubbed on car plastics restores a deep factory sheen that even surprises seasoned mechanics

➡️ A father splits his will equally between his two daughters and son: but his wife says it’s unfair because of wealth inequality: “They’re all my kids”

Animals will notice before many of us do. Chickens may head for their roosts. Cows may stand unsure in paddocks that feel like sudden evening. Crickets might begin their night chorus. A wind, sometimes, rises—a subtle coolness as the sun’s heat is briefly throttled.

Then, the last sliver of sun will vanish. In that instant, safe viewing rules change: during full totality, and only then, the naked eye can drink it in. The sky will drop into a deep, improbable blue-black. Venus and perhaps other planets will shimmer into visibility. Around the black disk of the moon, the corona will spread in pale feathers of fire, ghostly and alive. For six minutes, give or take, the world inside the path will exist somewhere between day and night, between science and story.

Some will shout. Some will weep. Some will grow very still. The arguments, the fear campaigns, the sermons and symposiums will all be there, echoing in the background, but the sky itself will not acknowledge them. It will simply do what it does, a dance of mass and distance playing out as it has long before we named it.

And then, as quietly as it began, the light will return. A single brilliant bead of sun will flare on the edge of the moon—the “diamond ring”—and the world will flinch at the sudden glare. Glasses will go back on. Shadows will soften. Birds will resume their arguments in the trees. Traffic will inch forward again. Notification chimes will ping as phones reconnect to networks strained by millions of simultaneous shares.

After the Darkness

In the weeks that follow, scientists will tally what really happened. They will look at hospital admissions, at mental health hotline volumes, at traffic statistics. Some will publish papers showing negligible changes. Others will find small blips—a local surge in anxiety here, an uptick in minor accidents there—and interpret them through their favored lenses.

Religious groups will sift the event for signs. Some will declare that catastrophe averted is itself evidence of divine mercy. Others will adjust their timelines, pushing predictions forward into some future eclipse, some other crisis. A few will quietly step back, the urgency of their warnings fading now that the shadow has passed and the world, stubbornly, remains.

For most people, though, the eclipse will settle into memory not as a crisis but as a story told in the warm light of kitchens and the soft glare of phone screens. “Were you there?” they’ll ask. “Did you see the way the temperature dropped?” Someone will describe the way their child grabbed their hand and whispered, “Is this safe?” as the sun slid away. Someone will confess that, for those strange minutes, their own daily worries—deadlines, debts, diagnoses—fell away under the weight of a sky gone dark.

In the end, perhaps the eclipse’s greatest power is not its potential to harm or to herald chaos, but its ability to remind us that we live on a moving, spinning stone, tethered by gravity to a star that owes us nothing. It pulls us, briefly, out of our narrow routines and sets us under a larger dome, one where shadows hundreds of kilometers wide can sweep across countrysides in the time it takes to brew a pot of coffee.

We will argue about it, fear it, mythologize it. But when the next great shadow comes—and it will, eventually, long after this “eclipse of the century” has slipped into textbooks and trivia—it will do so on its own indifferent schedule. Our role, small and fleeting, is to watch, to protect our fragile eyes and fragile minds, and perhaps, for a few trembling minutes, to feel both insignificant and deeply, wildly alive.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the eclipse itself dangerous to my health?

The eclipse does not emit any special or extra radiation. The main physical danger comes from looking directly at the sun without adequate eye protection during the partial phases. Psychological stress or anxiety can rise because of intense media coverage and personal fears, but the shadow itself is not inherently harmful.

How can I safely watch the eclipse?

Use properly certified eclipse glasses that meet international safety standards, or view it indirectly with a pinhole projector or similar method. Only during the brief period of full totality—when the sun is completely covered—is it safe to look with the naked eye, and you must put protection back on as soon as the first bright sliver reappears.

Will animals and nature be affected?

Yes, but usually in temporary and harmless ways. Birds may roost, insects may begin their nocturnal sounds, and some animals behave as if evening has arrived. These changes typically last only as long as the light is altered, and normal patterns resume soon after.

Could the eclipse cause power outages or damage technology?

Modern infrastructure is designed to handle natural variations in sunlight. Solar power output will dip along the path of the shadow, but grid operators can plan for this in advance. The eclipse does not normally damage satellites, communications, or electrical systems.

Why do some religious or spiritual groups call it a sign or omen?

Throughout history, eclipses have been interpreted as meaningful messages from the divine or the universe. Their rarity, visual drama, and ability to alter the sky make them powerful symbols in many traditions. While science explains their mechanics, personal and cultural interpretations give them additional layers of meaning for many people.