The memory arrives before you even know you’ve invited it. You’re rinsing dishes, or standing in line for coffee, or sitting in traffic at a red light, and suddenly you’re not there anymore. You’re back in a high school hallway that still smells like floor polish and cheap perfume. You’re on a beach in late summer, skin salty, light pooling on the water like melted metal. Or you’re replaying that argument from three years ago, the words you wish you’d said echoing more clearly now than anything that actually came out of your mouth that night.

It feels almost physical, this slipping into the past. Your chest tightens, your shoulders shift, your breath changes tempo. It’s as if your nervous system doesn’t know that this moment is finished, boxed, archived. Part of you is convinced it might still be happening somewhere, and if you think about it hard enough, maybe you can edit it, rearrange it, redeem it.

If you catch yourself often replaying old scenes—good, bad, or impossibly bittersweet—you’re not alone. Psychology has a lot to say about why we do this, but the story is more tender than you might expect. It’s not just overthinking. It’s not just nostalgia. It’s your mind trying to complete emotional business that, for whatever reason, still feels unfinished.

The Hidden Work Your Mind Does in the Background

Imagine your brain as a small cabin with a single light on inside at night. From the outside, nothing looks like it’s happening. But inside, someone is quietly sorting, stacking, labeling boxes. That’s what memory replay is, in a way: silent, interior work. It may feel pointless, even obsessive, but often it has a purpose—especially emotional.

Psychologists sometimes talk about rumination: going over the same scene again and again, especially painful ones. But they also talk about meaning-making and emotional processing, those slow internal processes that help us understand what happened, who we are now because of it, and how we want to live going forward.

Think about the last time you replayed a moment intensely. Maybe it was the time someone broke your trust, or the day you moved out of a place that held a hundred small, quiet joys. When that memory rises uninvited, your body remembers with you: your jaw takes on the old tension, your stomach folds into the previous dread, or you feel that spread of warmth in your chest as if the sun from that day is still on you.

Psychologically, this isn’t random. The memory is a kind of emotional file your mind hasn’t fully closed yet. It reopens it, not to torture you (even if it feels like that sometimes), but to ask one insistent question: What does this still mean to you?

Replaying the Past as Emotional Sense-Making

The human brain is a pattern-hungry storyteller. It is always trying to connect dots between “this happened” and “this is who I am now.” When a past moment refuses to leave you alone, it often means your mind is still building a bridge between experience and identity.

Maybe you keep revisiting an old failure because some part of you is trying to decide: Was that a moment I wasn’t enough, or a moment I was brave for even trying? Or you replay an ended relationship because, beneath all the scenes and dialogues, you’re searching for a narrative that doesn’t end with, It was all my fault or It was all theirs, but something more nuanced, more human.

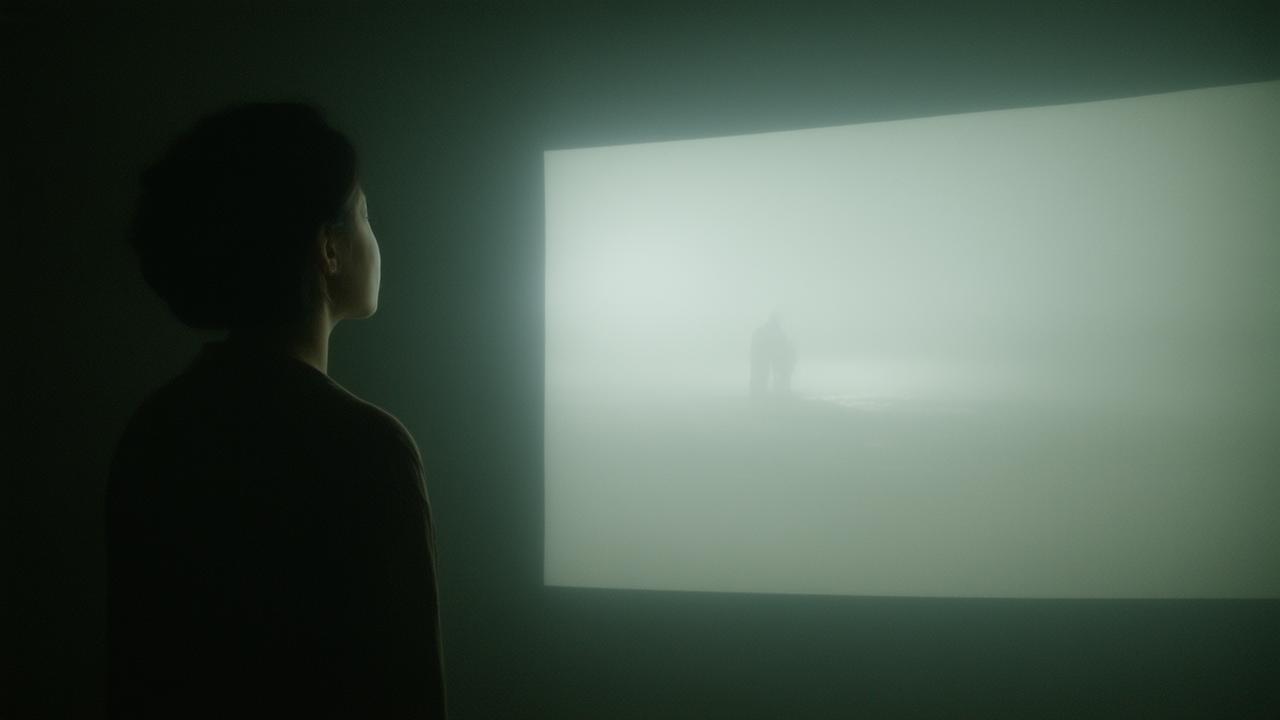

From an emotional perspective, those returns to the past can be a workshop. You’re not just watching the same film; you’re editing it. You’re moving the camera, zooming in on expressions you missed, adding inner commentary you didn’t have the language for at the time. Each replay is a new attempt to see the moment from a different vantage point: more compassionate, more informed, sometimes more honest.

Why Some Memories Won’t Stop Knocking

Of course, not all memories get equal airtime. Some drift away quietly. Others cling like burrs to your clothing, snagging your attention whenever life slows down enough for them to catch up. There are reasons certain moments become “sticky.”

Emotionally intense experiences, especially those that involve shame, loss, joy, or danger, are tagged by your nervous system as “important.” Your brain doesn’t always know exactly why they’re important yet, only that they are. So it keeps bringing them back for review, like a teacher returning an essay again and again, saying, “Look at this part. There’s more here.”

Consider how these different emotional purposes can show up:

| Type of Memory Replay | What It Often Feels Like | Possible Emotional Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Reliving a painful argument | Tense, restless, mentally drafting better comebacks | Trying to regain a sense of power or fairness; protecting self-esteem |

| Replaying a time you were rejected | Embarrassment, tight throat, sudden self-criticism | Searching for an explanation; guarding against future hurt |

| Revisiting a perfect day | Warmth, longing, subtle ache | Savoring meaning; reminding yourself what matters most |

| Imagining different outcomes | “What if” loops, mental rewrites of the past | Learning, rehearsing new responses, rebuilding a sense of agency |

| Replaying losses and goodbyes | Tears close to the surface, soft sorrow | Grieving at your own pace; staying connected to what you loved |

Notice how often the emotional purpose is not cruelty, but protection. Your mind is trying, in its clumsy way, to help you feel safer, clearer, more prepared, even when the method leaves you feeling exhausted.

Nostalgia: When Memory Is a Place You Visit for Warmth

Not every replay is heavy. Some are gentle returns to what once felt whole. A certain song, a particular angle of afternoon light, the smell of rain on hot pavement—suddenly you’re back on a road trip with friends, or in your grandmother’s kitchen with steam rising from a pot on the stove.

Psychologically, this is nostalgia, and research suggests it can actually stabilize mood, especially when we feel lonely or unsettled. These rewinds can serve as emotional campfires: small, bright pockets of warmth in which we remember that we have known joy, belonging, and tenderness, even if the present feels shaky.

Nostalgic replay says, Look, you have chapters behind you that were worth living. That means you’re capable of more of them. It is not an attempt to drag you backward, but to reassure you that the story of your life has included love and meaning, and likely will again.

When Replaying Becomes a Trap Instead of a Tool

There is a line, though, where replay shifts from emotional processing into emotional quicksand. You know you’ve crossed it when you no longer feel like you’re learning anything from the memory, or seeing it from new angles—you’re just stuck inside it, circling the same sense of shame, anger, or helplessness.

This kind of mental time travel can look like lying awake at 2 a.m., heart racing as if that awkward conversation from eight months ago is happening again right now. It can look like reliving a breakup so relentlessly that every new person who enters your life gets filtered through that same grainy footage, as if they’re just an echo instead of someone new.

Psychology distinguishes between processing and rumination. Processing is fluid: the story slowly changes, softens, widens. Rumination is rigid: same scenes, same judgments, same stuck feeling. In rumination, the emotional purpose has been hijacked. What began as an attempt to understand or protect you now keeps you rehearsing pain without moving through it.

Listening for What the Memory Is Asking From You

One gentle shift is to stop asking, “Why can’t I stop thinking about this?” and instead ask, “What is this memory still trying to do for me?” That small reframe turns the past from an enemy into a messenger.

Sometimes the message is about boundaries: you replay a situation because part of you knows, Next time, I need to say no sooner. Sometimes it’s about grief: the replay is a protest against finality, your heart saying, I’m not ready to accept that this is over. Sometimes it’s about identity: you’re asking, Who was I in that moment, and who do I want to be now?

If you can name the emotional purpose, you can respond to it more directly. If the memory is about safety, you might take practical steps to protect yourself in the present. If it’s about loss, you might create a small ritual—writing a letter, visiting a meaningful place, or even just lighting a candle—to acknowledge that grief is allowed to exist.

➡️ This small adjustment helps reduce the feeling of bodily overload

➡️ What it means psychologically when you avoid talking about yourself, even when asked

➡️ I noticed my stress dropped once my cleaning goals became realistic

➡️ This is how to show interest without forcing enthusiasm

➡️ The one breathing mistake most people make daily without realizing it affects their stress levels

➡️ Why doing one task at a time is healthier than multitasking

➡️ I realized my cleaning system was built for a life I don’t live

Turning Replays Into Gentle Teachers

It can help to imagine yourself stepping slightly to the side of the memory, rather than into it. Instead of becoming your younger self again—body braced, heart racing—you become an observer sitting quietly in the back row, watching the scene unfold with kinder eyes.

You might ask:

- What was I needing that I didn’t have words for back then?

- What did I handle better than I give myself credit for?

- What do I know now that I didn’t know then?

These questions nudge the replay toward growth instead of self-punishment. They let the memory become a teacher: not a strict, unforgiving critic, but a wise elder saying, This was hard, and it mattered, and you are allowed to learn from it without hating yourself for not knowing better sooner.

When you look closely, many replays are love letters in disguise—messages from the parts of you that are still tender, still scared, still longing. The mind brings those moments back into the light, asking: Can you see me now, with more kindness than before?

Letting the Past Visit Without Letting It Move In

The goal is not to banish memory from your life. That would mean exiling huge portions of who you are. Instead, there is a quieter, more humane aim: to allow the past to visit without letting it take over your entire house.

When a replay arrives, you might experiment with a small mental ritual. You notice: Oh, we’re back here again. You name what the memory is about: This is the day everything changed or This is the time I felt most alive. You feel the emotional tide rise—and instead of fighting it or drowning in it, you let it wash over you for a moment.

Then, gently, you bring your attention to something anchor-like in the present: the sensation of your feet on the floor, the sound of birds outside, the weight of the mug in your hand. You don’t slam the door on the memory. You just let it know: I see you, I’m learning from you, and I’m also allowed to live here, now.

Because that is the quiet irony of psychological time travel: we revisit old moments not because we truly want to stay there forever, but because some part of us is still trying to figure out how to move forward more whole, more awake, and more at peace.

FAQs

Is it normal to constantly replay past moments?

Yes. Replaying is a common human experience. It often reflects your mind trying to process strong emotions, make sense of past events, or protect you from repeating painful experiences. It becomes a concern mainly when it feels compulsive and interferes with your daily life.

How do I know if I’m processing or just ruminating?

If revisiting a memory occasionally brings new insight, softer feelings, or a broader perspective, you’re likely processing. If it feels like the same loop—same judgments, same distress, no new understanding—you’re probably ruminating.

Can positive memories be a form of avoidance?

Sometimes. Nostalgia can be comforting and healthy, but if you spend most of your time mentally living in “the good old days” because the present feels unbearable, it may be a sign you’re using memory to avoid current challenges or emotions.

Why do embarrassing memories from years ago still hurt?

Moments that threaten our sense of worth or belonging get strongly encoded. When they resurface, your body can react as if the social threat is still active. That sting is often your nervous system trying to guard you against similar pain, even long after the moment has passed.

What can I do when replaying the past makes me anxious?

You can gently name what’s happening (“I’m replaying that moment again”), notice what the memory might be trying to protect or teach you, and then ground yourself in the present through your senses. If the anxiety is intense or persistent, it can help to talk with a therapist who can guide you through more structured ways of processing.