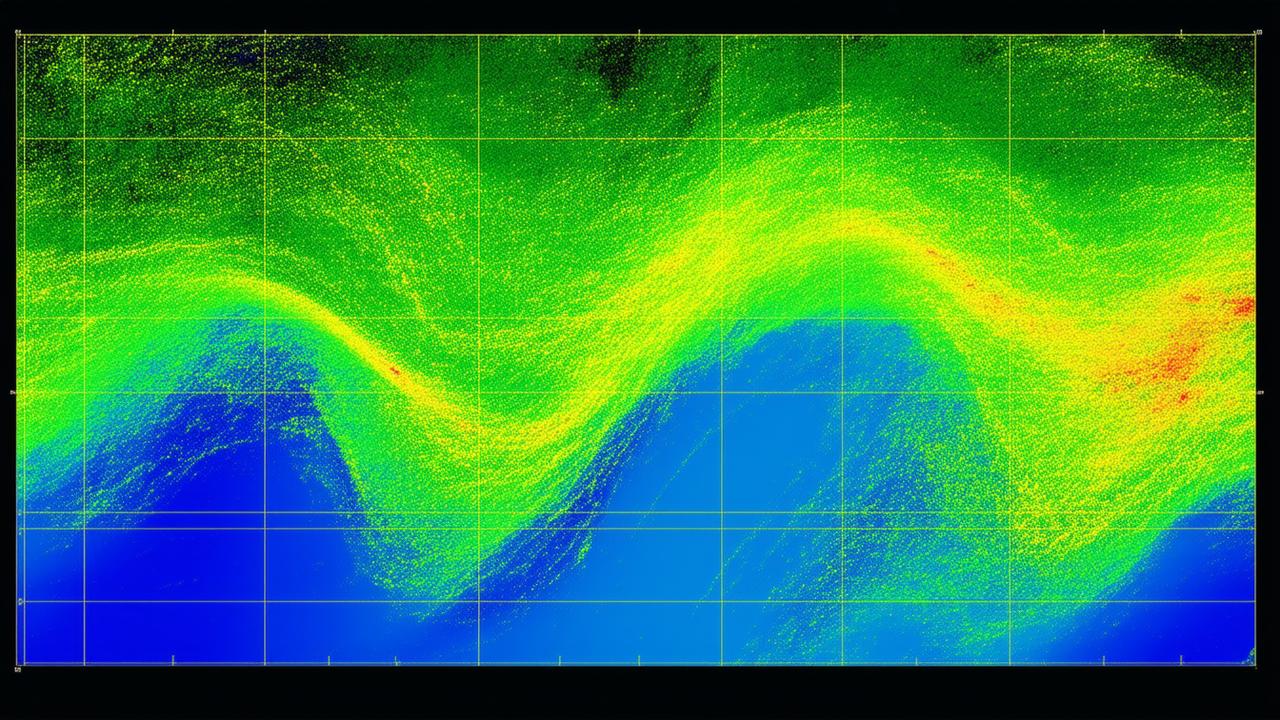

The first hint that something was off came as a color on a computer screen—a smear of deep, impossible red over the top of the world. It was just after dawn in early February, and the Arctic, that place we like to imagine as eternally white and numb with cold, was glowing hot on the monitor in a dim forecasting room. A meteorologist leaned in, squinting. The numbers beside that red band looked wrong, as if the software had skipped a line, or the sensor had glitched. It hadn’t. The Arctic was warming—again—but this time, it was doing something that left even the people who stare at these maps all day a little shaken.

The February That Didn’t Feel Like Winter

Outside the cities, far from the screens and servers, the change didn’t show up as a red blob. It arrived as the wrong sort of air on the skin. In northern Norway, it felt like a sly thaw sneaking in weeks early, water trickling in ditches that should still have been locked in ice. On the coasts of Alaska, hunters read it in the slush-soft sea ice—broken, unreliable, pocked with dangerous leads. In small Inuit communities, elders tilted their heads to the sky, listening to winds that no longer kept the old patterns, and said quietly, “This is not how February is supposed to sound.”

By the time those stories filtered back to the scientists, they were already seeing it in the numbers: Arctic air temperatures surging far above normal, sea ice thinning and retreating when it should have been thickening and spreading, storm tracks curving in unfamiliar arcs. A few of the world’s leading meteorologists began writing internal notes that, weeks later, would leak out onto social media and spark a wave of outrage, confusion, and fear:

“We may be watching the Arctic enter a state our climate models never really captured.”

“This Shouldn’t Be Happening Yet”

The world’s climate models—the massive, sophisticated computer systems that simulate the planet’s future—are built on physics and decades of data. They have gotten many things right: that the world would warm as we burned fossil fuels, that heatwaves would grow fiercer, that the Arctic would lose ice and snow. But they also rest on assumptions, averages, and smooth curves of change that unfold over time. They are not designed for surprises that come like a sharp knock at the door.

In early February, that knock was loud.

A sharp pulse of warm, moist air surged northward, slipping over a sea that has been losing its lid of ice year after year. Air masses that once stalled further south now raced toward the pole over waters that stayed strangely exposed and dark, hungry to soak in sunlight and give it back as heat. Temperatures in some parts of the Arctic spiked 15, 20, even 30°C above what used to be considered normal for the season.

“This shouldn’t be happening yet,” one forecaster wrote in a private Slack channel, watching the anomaly maps deepen. “Not at this scale, not with this persistence.”

A Table of Trouble: What the Numbers Are Whispering

It’s easy to dismiss this as one wild winter. Weather is chaotic; flukes happen. But line up the numbers from recent years, even in a simple table, and a pattern starts to emerge—a slow, insistent trend that suggests the Arctic is moving ahead of schedule while our models lag behind.

| Indicator | Early 2000s (Typical) | Last 5 Years (Observed) | Climate Models (2050 Projections) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter Arctic temperature anomaly | +0.5 to +1.0°C | +3 to +5°C in many regions | +4 to +6°C |

| February sea ice extent (relative to 1981–2010) | Slightly below average | Consistently near record lows | Projected low but not record-breaking every year |

| Days of above-freezing temperatures near the pole in mid-winter | Essentially zero | Occasional, short-lived events | Expected to become more frequent by mid-century |

| Thickness of multi-year sea ice | Much thicker, widely distributed | Significantly thinned, patchy | Modeled to decline more gradually |

When researchers place current observations next to those model projections, one uneasy question keeps surfacing: Have we underestimated how fast the Arctic can change?

Inside the Forecast Rooms: When Maps Feel Like Warnings

In meteorology offices from Copenhagen to Seattle, February’s data rolled across screens with a familiar hum: satellite feeds, reanalysis datasets, numerical model outputs updating around the clock. These places are usually calm. Forecasters are trained to be skeptical, to double-check, to shrug at the latest headline-grabbing “record” because weather records fall all the time.

This time, they didn’t shrug.

A veteran forecaster in Europe watched the projected path of a powerful storm curling toward the Arctic, drawing up huge volumes of Atlantic heat behind it. He had seen similar tracks before, but not in February with this intensity, over ice this fragile. “It’s like the guardrails have moved,” he later told a colleague. “We’re in the same road, but the curves don’t behave like they used to.”

Another team, specializing in seasonal outlooks, ran their models again and again, tweaking initial conditions, trying to make sense of the stubborn warmth in the high north. Each rerun told a similar story: the Arctic was not simply fluctuating around a familiar mean; it was edging into a different state, where thin ice, warm seas, and altered winds fed each other in feedback loops the models only partially captured.

Outrage spread not because one weird winter suddenly “proved” climate models useless, but because the signs pointed to something more subtle and unsettling: that the models might be conservative where it hurts the most. The edge of the map—the Arctic, that white cap at the top of our globe—may be shifting faster than the tools we use to predict it.

Uncharted Territory: What “Model Failure” Really Means

When people hear that climate models might be “dangerously wrong,” it’s tempting to imagine everything is broken—that scientists have no idea what’s happening. Inside the research community, the fear is almost the opposite: that the broad direction is right, but the pace, the extremes, and the tipping points have been underestimated.

Meteorologists are not claiming the laws of physics have changed. Instead, they’re noticing that some ingredients in the Arctic system—like how quickly ice disappears once it thins, or how fast warm ocean currents chew at its underside, or how stubbornly warm, moist air can now invade polar latitudes—might not be fully represented in the models at the resolutions we run today.

Picture a map drawn at low detail. You can see the coastline, the big bays, the shape of the land. But the small inlets, hidden reefs, and narrow channels are blurred. You can still navigate, but when the weather turns wild, those missing details can be the difference between a safe passage and a shipwreck. Our climate models may be like that: good enough to guide us, but missing the sharp edges where extremes are born.

In the Arctic, those extremes matter. A mid-winter thaw that once would have been unthinkable can warp the snowpack, destabilize sea ice used as a highway by Indigenous hunters, confuse animals that time migrations by the length of the cold season. A series of such events can reorganize the ecosystem, species by species, until the Arctic we thought we knew becomes something else, faster than projected.

Ripples From the Top of the World

The outrage that flared in early February wasn’t only about the Arctic itself. It was about what a rapidly changing pole means farther south, where most of us live our lives under increasingly restless skies.

A warming Arctic can disturb the jet stream—a high-altitude river of air that steers storms and divides cold from warm. When that river wobbles, buckles, or slows, weather patterns can lock in place for unnervingly long stretches. Think of stubborn winter cold snaps that won’t let go, or stalled heat domes that turn a week of discomfort into a deadly month.

Some scientists argue fiercely over just how strong this connection is; others caution against drawing straight lines from every odd storm to the Arctic’s fever. But as unseasonal warmth spreads over the pole again and again, those arguments are taking on a new urgency. If the Arctic is racing ahead of schedule, then the jet stream, storm tracks, and rainfall patterns we rely on for everything from farming to infrastructure design may be more vulnerable than our planning assumes.

In a riverside town thousands of kilometers from the nearest glacier, a farmer doesn’t need to know the exact temperature anomaly at 80°N. She only needs to know whether the models telling her what next season might look like are erring on the side of safety—or false comfort.

What We Do When the Map Looks Wrong

Back in that early morning forecasting room, the meteorologist who first noticed the red smear over the Arctic didn’t walk away. He pulled colleagues in, started comparisons, filed reports, joined late-night calls with researchers in other time zones. That’s what scientists do when the map and reality start to diverge: they test, argue, adjust.

➡️ What psychology reveals about people who feel emotionally drained after small social interactions

➡️ I stopped timing my cleaning sessions and my house became easier to maintain

➡️ I made this simple recipe and didn’t change a thing

➡️ If your flowers fade quickly, temperature stress is often the reason

➡️ Why your body feels heavier on some days even when nothing is wrong

➡️ A small daily habit that helps your body feel more balanced

➡️ Climate panic or scientific fact Februarys predicted Arctic collapse and extreme anomalies split experts and fuel public distrust

Already, the climate community is pushing for models that resolve the Arctic in finer detail, that better simulate sea ice dynamics, that draw sharper coastlines around the uncharted places. Observing systems—satellites, drifting buoys, on-ice sensors—are being upgraded and expanded, because you cannot model what you do not see clearly.

But the deeper choice is not only technical. It’s about how we respond to the possibility that the crisis is running hotter and faster than our best estimates. The outrage of meteorologists and climate scientists is not the outrage of helplessness; it’s the frustration of knowing that lagging models can be seized upon as an excuse to delay action, when in reality they may be underselling the danger.

If the Arctic is indeed entering uncharted territory, then “waiting for better data” becomes a risky form of denial. It nudges us toward a world where adaptation plans undershoot the threat and mitigation efforts stall while the ice, quite literally, melts from under our feet.

And yet there is one thing these turbulent February signals make painfully, usefully clear: uncertainty cuts both ways. If models can be wrong, they can be wrong in the direction of underestimating both damage and the benefits of fast, decisive cuts in fossil fuel use. Every fraction of a degree avoided slows the changes bearing down on the Arctic, and with them, some of the sharpest edges of risk for the rest of us.

Listening to the North

When scientists say the Arctic is entering uncharted territory, it can sound abstract, like a line from a press release. But listen closer.

It’s in the muted crunch of thinning ice under a hunter’s boots, where once the surface rang solid and sure. It’s in the muffled February rain on snow in a coastal village where elders remember crisp stars and biting dry cold. It’s in the uneasy murmurs in forecast offices as red anomalies bloom again across the top of the world, earlier, stronger, stranger than expected.

The maps and the stories are aligning, and together they tell us something simple and hard: we are pushing the Arctic into a climate no human culture has ever known. The models, our carefully drawn guides to the future, may be trailing behind the pace of that push.

We still get to choose how far we go into that unknown. But the signals from early February—the red smears, the wrong-feeling air, the outraged messages between meteorologists—are asking us, urgently, to stop pretending that the old charts are enough.

The top of the world is speaking in the sharp language of records shattered and patterns broken. The question now is whether we’re willing to listen—and act—before “uncharted territory” becomes simply, irreversibly, the new normal.

FAQ

Are climate models completely unreliable if the Arctic is changing faster than expected?

No. Climate models have correctly predicted many broad trends, including overall global warming and Arctic sea ice decline. The concern is that in certain regions and extremes—like rapid winter warming in the Arctic—they may be too conservative, underestimating the speed and severity of change. They are still vital tools, but they need constant refinement and should be used with awareness that reality can sometimes outpace projections.

Does this mean scientists were wrong about climate change?

Not about the fact of climate change or its primary cause. Scientists have long warned that burning fossil fuels would warm the planet and strongly affect the Arctic. What may be “wrong” in some cases are the timelines and the intensity of certain impacts, which appear to be arriving sooner or in more extreme forms than many models suggested.

Is one weird February enough to claim the Arctic is in uncharted territory?

One month alone is not proof of a new climate state. However, this February fits into a longer pattern: repeated record-breaking warmth, shrinking and thinning sea ice, and unusual weather events in the high north. Taken together, these point toward a rapidly shifting Arctic that is pushing beyond the ranges represented in many older simulations.

How could a rapidly warming Arctic affect weather where I live?

A warming Arctic can influence the jet stream and storm tracks, potentially leading to more persistent weather patterns—such as long-lasting cold spells, heatwaves, or heavy rain events. The exact effects vary by region and are an active area of research, but what happens at the pole does not stay at the pole; it can ripple through the entire climate system.

What can be done if our models are underestimating the risk?

Several steps are crucial: improving observations in the Arctic, refining climate and weather models to better represent polar processes, planning infrastructure and adaptation measures with a safety margin for worse-than-expected outcomes, and most importantly, rapidly cutting greenhouse gas emissions. Acting sooner reduces the chance that reality will outrun even our best forecasts.