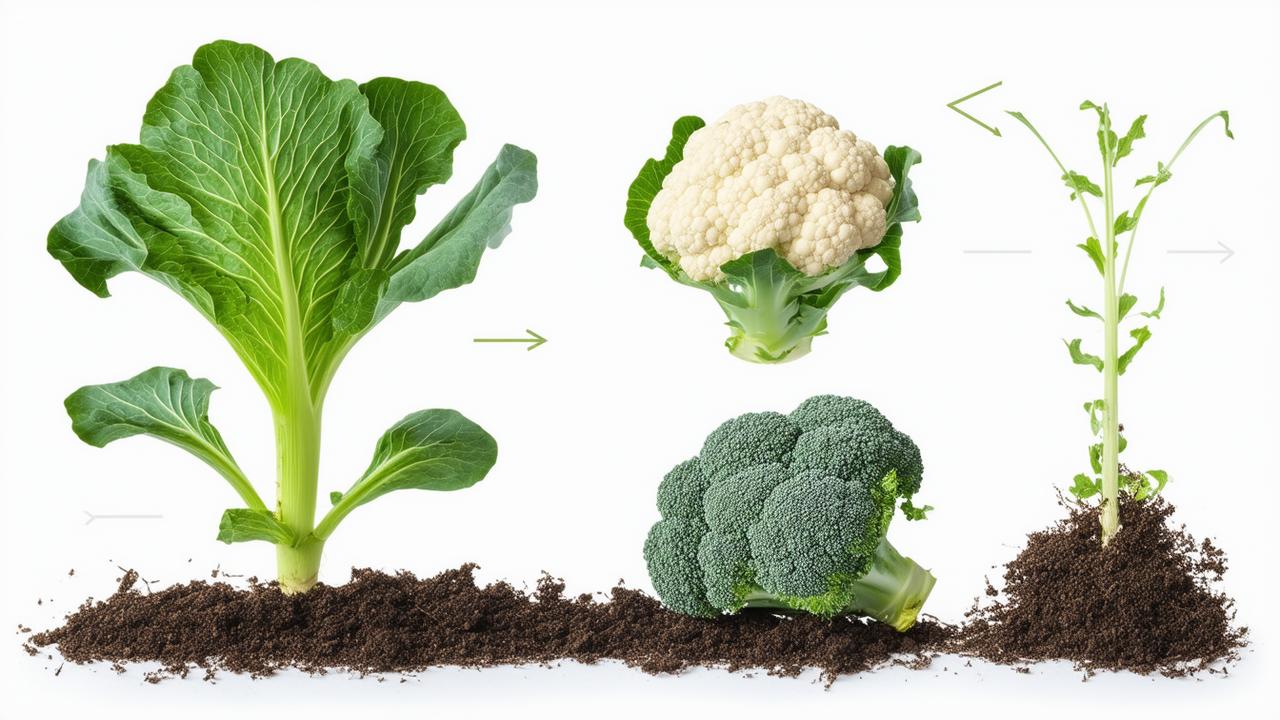

The first time I saw a field of wild brassicas, I walked right past it. The plants were leggy and unremarkable, with yellow flowers tossed about in the wind like confetti someone forgot to sweep up. Nothing about them whispered “cauliflower” or “broccoli” or “cabbage.” Yet botanically, they were the same story at its beginning—an ancient, scruffy ancestor of vegetables that now sit, prim and curated, in our refrigerators. Many people don’t realize it, but that tight white cauliflower, the brooding green broccoli, and the humble cabbage head are all varieties of one single species: Brassica oleracea. It’s as if one plant decided to try on a half dozen different personalities and never took any of them off.

The Wild Ancestor by the Sea

Imagine a salty wind rolling off European cliffs, the kind that stings your cheeks and leaves a taste of the ocean on your lips. Clinging to those cliffs, in rocky niches and thin soil, grows a rugged, almost stubborn plant: wild cabbage, or wild Brassica oleracea. It doesn’t look like much. Loose leaves, a lanky shape, flowers the color of dandelions. Yet inside that unassuming body sits genetic potential so flexible that, over centuries, humans would stretch it into entirely different shapes.

Early coastal communities didn’t care about genetic potential. They cared about survival. This wild cabbage, tough enough to handle salt spray and poor soil, offered leaves to pick, chew, boil, and endure long, cool seasons. Those who gathered it noticed small differences: some plants with thicker leaves, some sweeter, some with tighter growth in the center, some with buds that swelled, some with stems that thickened just so. Without realizing it, they were looking at the seeds of culinary diversity.

When people selected and saved seeds from the plants they liked best, they weren’t just harvesting; they were editing. Over generations, that quiet editing wrote an entirely new chapter in the story of Brassica oleracea. Humans nudged this seaside scrapper toward becoming the vegetables we know today—cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, kohlrabi—each a different expression of the same ancestral body.

The Shape-Shifting Plant

To really grasp how wild cabbage became our garden favorites, you have to think the way a patient farmer might have, thousands of years ago. You’re walking through a small plot at dusk, your fingers brushing leaves still holding the day’s warmth. One plant catches your eye: its leaves curl tighter around the stem, forming a small, dense heart. So you mark it, mentally or with a tied scrap of cloth. That plant gets to be a parent.

Over decades and then centuries, this simple act—saving seeds from plants with more tightly packed leaves—transforms the species into cabbage. A cradled core of leaves, layered like secrets. Another farmer, somewhere else, isn’t captivated by leaves. They’re fascinated by flower buds, the tight clusters at the end of the branching stems. They save seeds from plants whose buds are larger, denser, more complex. Their descendants become broccoli, and, through a slightly different preference—larger swollen flower heads—cauliflower.

It’s the same plant, but humans kept rewarding different quirks. One group fell in love with leaves (cabbage, kale). Another adored buds (broccoli, cauliflower). Others even admired funny bulging stems (kohlrabi) or tiny mini-cabbages along a stalk (Brussels sprouts). When you stand in a grocery aisle, looking from one to another, you’re really looking at selected body parts of Brassica oleracea, each carefully emphasized over centuries.

How the Same Species Becomes Different Veggies

This is the part that still feels like magic, even when science explains it. Cauliflower, broccoli, and cabbage share almost the same genetic blueprint. But different parts of that blueprint are dialed up or down. It’s like three siblings using the same wardrobe but styling their outfits completely differently.

In cabbage, the plant’s energy funnels into forming layers and layers of leaves that wrap tightly around each other. In broccoli, the energy flows upward into thick stalks and a bouquet of compact flower buds. In cauliflower, that energy is pushed even further into an enormous, condensed mass of immature flower tissue—the familiar white “curd” we slice into steaks or break into florets.

The stems, the buds, the leaves—each vegetable is just the plant focusing its growth in a slightly different place. And for thousands of years, people noticed, rewarded, and exaggerated those differences. Without laboratories, without genetic sequencing, they did their own slow-motion plant engineering with nothing but sharp observation and saved seeds.

A Family Reunion on Your Cutting Board

Picture your kitchen counter on a busy cooking night. A head of cauliflower sits beside a stack of broccoli crowns and a dense green cabbage. The cutting board is soon sprinkled with pale crumbs of cauliflower curd, deep green broccoli beads, crisp shavings of cabbage. The smells mingle—sweet, brassica-sharp, earthy.

If plants had consciousness, this might feel like a family reunion. Broccoli’s branching stems, the tight, brain-like curls of cauliflower, the leafy, layered dome of cabbage—they’re all just riffs on one ancestral theme. Their similarities whisper if you look closely. The way the leaves clasp the stem. The smell when you slice into them: that faint sulfur, warm and vegetal. The yellow blossoms they’d all eventually bear if you abandoned them in the garden a bit too long.

We usually group vegetables by how we use them—“roasting veg,” “salad veg,” “stir-fry veg.” But in the botanical sense, cauliflower and cabbage are closer to each other than carrot is to carrot top, or potato is to tomato. Your coleslaw, your roasted broccoli, your cauliflower curry? Same species, different moods.

Cooking with Cousins

Once you start seeing cauliflower, broccoli, and cabbage as cousins in the same family, something subtle shifts in your kitchen. You realize they can often trade places. The cabbage you shredded for slaw can be charred in wedges on a hot pan the way you might treat cauliflower “steaks.” Broccoli stalks—if you trim and peel them—cook up with a tenderness reminiscent of cabbage core. Cauliflower florets, roasted until their edges brown and crisp, give off the same caramelized sweetness you get when you pan-sear thick slices of cabbage.

Their shared lineage comes through in flavor, too. That hint of mustardy bite, that earthy depth that pairs so well with garlic, lemon, and olive oil; the way they all soften with slow cooking into something almost silky. Understanding that they’re one species offers permission to play: swap cabbage into a pasta dish that calls for broccoli, or fold roasted cauliflower into a recipe meant for stir-fried greens. Often, it just works—because underneath your improvisation, the plant is the same.

| Variety | Part We Eat | Signature Trait |

|---|---|---|

| Cabbage | Leaves | Tight, layered head of overlapping leaves |

| Broccoli | Flower buds & stems | Branched stalks topped with green buds |

| Cauliflower | Immature flower head | Dense white (or purple, orange) “curd” |

| Kale | Leaves | Loose, often curly or frilled leaves |

| Brussels Sprouts | Leaf buds | Mini “cabbage heads” along a tall stalk |

The Invisible Work of Farmers and Gardeners

Behind this simple table of traits lies centuries of quiet, persistent human attention. Most of the transformations that turned wild cabbage into familiar vegetables happened long before scientific plant breeding had a name. The process was personal and local: a farmer in one village selecting firm, round heads year after year; a gardener in another valley keeping seeds only from plants with huge, compact flower clusters.

The fields smelled of soil and sweat and plant sap; hands got stained green; the decisions were made with the eyes and the nose and the tongue. Did this plant survive the winter better? Did that one cook down into a sweeter stew? In a world without supermarkets, such questions were matters of survival, not preference.

Today, when you pick up a plastic-wrapped head of cauliflower, the chain back to those patient ancestors is easy to miss. Yet every floret you snap off carries the invisible fingerprints of generations who chose, saved, and sowed. The modern versions might be more uniform, more predictable, but they’re still part of that same long, living conversation between humans and plants.

➡️ Nasa receives 10-second signal sent 13 billion years ago

➡️ Is it better to turn the heating on and off or leave it on low ?

➡️ If the ATM keeps your card this fast technique instantly retrieves it before help arrives

➡️ Never leave your bedroom door open at night even if you think it is safer open the shocking truth that firefighters and sleep experts do not want you to ignore

➡️ How to make a rich, restaurant-quality pasta sauce at home using only 4 simple ingredients

➡️ Probably F?15s, F?16s, F?22s And F?35s : Dozens Of US Jets Now Converging On The Middle East

➡️ Neither tap water nor Vinegar: The right way to wash strawberries to remove pesticides

Seeing the Species in the Supermarket

Next time you walk through the produce section, imagine the labels stripped away. No price tags, no tidy names. Just shapes and colors and textures. You reach for a cabbage and a cauliflower; your hands are nearly the same distance apart on the tree of life as if you’d picked up two apples from the same branch.

Once this sinks in, the supermarket starts to look different. The brassicas—cauliflower, broccoli, cabbage, kale, Brussels sprouts—form a little silent family gathering in the cold, misted shelves. Carrots and parsnips are cousins, too. Potatoes and tomatoes, same species? No. But their kinship is there at a higher level. Our food system becomes a web of relationships instead of a flat shopping list.

That mental shift can nudge other changes. You might waste less if you see broccoli stems as close kin to cabbage. You might experiment more, testing how your favorite cauliflower recipe works with shredded cabbage or whole wedges of broccoli stalk. You might feel, just a touch, more connected to the plants themselves—and to the people who shaped them.

A Different Way of Looking at Your Plate

There’s a quiet wonder in realizing that your dinner is not just a set of ingredients but a record of evolution and culture. The pale cauliflower in your roasting pan is a flower head that forgot how to become a flower. The broccoli beside it is a cluster of buds frozen in time by human preference. The cabbage in your salad is a leafy rosette so condensed it became a sphere.

All three are one species, stretched into variety by time, place, and human desire. What we often think of as “different vegetables” are, in this case, different ideas about what a plant could be, made solid. Bite by bite, we participate in that story—without ever having stood on a windswept cliff and plucked a leaf from the wild original.

Sometimes the most familiar foods hide the strangest truths. Cauliflower, broccoli, and cabbage aren’t strangers jostling for space in the crisper drawer. They’re siblings from the same ancestral home, still carrying the taste of wind, rock, and sea, still responding to our choices, still changing—quietly, patiently—every season we plant another seed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are cauliflower, broccoli, and cabbage really the same species?

Yes. They are all cultivated varieties of the species Brassica oleracea. Despite looking very different, they share the same basic genetic blueprint.

Why do they look so different if they are the same plant?

Over centuries, humans selectively bred wild cabbage for specific traits—tighter leaves, bigger flower buds, thicker stems. Emphasizing different plant parts created distinct forms: cabbage (leaves), broccoli (flower buds and stems), and cauliflower (a dense flower head).

Do they have similar nutritional benefits?

They share many nutrients: vitamin C, fiber, and various beneficial plant compounds. Each has its own strengths—broccoli is rich in certain antioxidants, cabbage is excellent for fiber, and cauliflower is versatile and low in calories.

Can I grow all three in the same garden?

Yes, but they have similar needs and can attract the same pests. Good spacing, crop rotation, and soil care are important. Because they are the same species, they may cross-pollinate if you are saving seeds.

Can I substitute one for another in recipes?

Often, yes. Cauliflower, broccoli, and cabbage respond similarly to roasting, stir-frying, and braising. Flavors and textures will change, but many recipes work well if you swap one brassica cousin for another.