The first time you see a raw image from deep space—really see it, before the color balancing, before the annotations and arrows—you realize how much of the universe is made of surprise. It’s often just a pale swirl, a faint ring, a smudge against velvet black. But lately, those smudges have been whispering secrets with a clarity we’ve never had before. Multiple spacecraft and observatories, scattered like metal fireflies around our solar system and beyond, are bringing back details so sharp, so strange, that even veteran scientists pause, blink, and mutter, “We didn’t expect that.”

A Sky Suddenly Full of Eyes

Step outside on a cold, clear night and tilt your head back. To your naked eyes, the sky is still the same old dome of stars: familiar constellations, a faint river of the Milky Way if you’re lucky enough to be far from city glare. But hidden beyond what your pupils can drink in, an armada is watching.

There’s the James Webb Space Telescope, floating at a quiet gravitational balance point, its honeycomb mirrors unfurling like some alien flower. There’s the aging but indefatigable Hubble, still snapping optical portraits. There are solar sentinels like the Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter, skimming closer to the Sun than any spacecraft before them, tasting the breath of our star. Around Mars, a small crowd of orbiters stares down at a planet that once had rivers and seas. At Jupiter, Juno loops through deadly radiation belts, listening to the gas giant’s interior like a cosmic stethoscope. Farther out, Voyager 1 and 2 drift in a realm where the Sun is only a bright star behind them, sending back whispers across billions of kilometers.

Each of these craft, and the observatories on Earth that join their gaze—ALMA in Chile, the Very Large Telescope, arrays peering in radio and X-ray and infrared—are pieces of a grand, improvisational symphony. They don’t just collect pretty pictures. They stitch together wavelengths our eyes can’t see, revealing a universe that is dustier, stormier, more turbulent and more alive than the postcard version in our heads.

The New Textures of the Cosmos

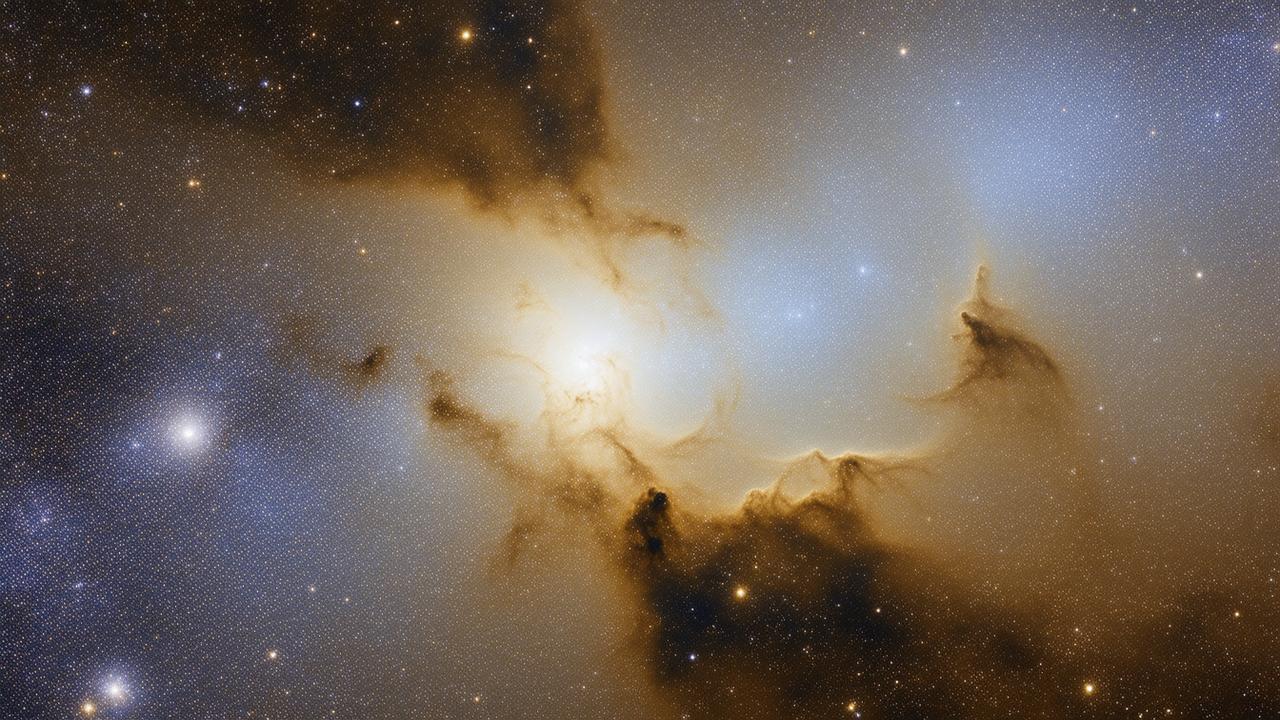

The universe, it turns out, has a lot of texture. Once, galaxies were swirls. Planets were dots. Nebulae were pastel smears printed on coffee shop posters. Then we started looking with sharper eyes.

Webb’s infrared gaze has turned once-blurry stellar nurseries into three-dimensional landscapes. In the famous “Cosmic Cliffs” of the Carina Nebula, what used to look like a blur now appears as towering walls of gas, carved by stellar winds into ridges and valleys. You can almost feel the grit of stardust under your nails just looking at it. The telescope sees heat where human eyes see darkness, pulling curtain after curtain away from star-forming regions. Behind those curtains: newborn suns, disks of gas and rock coalescing into future planets, and jets of material screaming into space at hundreds of kilometers per second.

ALMA, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, has been tracing the coldest ingredients in those same regions—molecules, ices, the raw inventory of creation. When its data sits alongside Webb’s and Hubble’s, we get not just a snapshot, but a layered map: where stars are born, where planets are assembling, where organic molecules might already be forming on drifting grains.

Even black holes, once a byword for “unknowable,” are taking on texture. The Event Horizon Telescope’s radio images of the black holes at the centers of M87 and our own galaxy, Sagittarius A*, have gone from the first fuzzy doughnut ring to increasingly detailed glimpses of how matter swirls and heats as it falls toward oblivion. That glow—the last scream of light before the plunge—now carries clues about magnetic fields, spin, and the choreography of extreme gravity.

Worlds Up Close: Familiar Yet Alien

Closer to home, robotic explorers have been quietly rewriting our sense of what a planet, a moon, even a wandering rock can be. You may have seen a photo of Jupiter a thousand times in textbooks, that banded ball with the single red eye. But Juno’s camera has recast it into something more like a living painting.

From Juno’s vantage, close to the cloud tops, the gas giant’s poles are crowded with storms that spin like clusters of bright teal roses. The famous belts and zones are not just color bands but vast, stacked layers of atmosphere, pierced by lightning storms so powerful they would swallow continents on Earth. The spacecraft’s instruments read deep into the planet, revealing that the Great Red Spot is a gigantic, planetary scar that sinks far deeper than scientists expected, like a storm-tunnel corkscrewing into the interior.

Saturn, too, has surrendered new secrets, especially after the late Cassini mission dove between the rings and the planet, tasting the composition of that glittering debris. Those rings, once thought to be almost pristine, turn out to be laced with complex contamination: organics, water ice, dust, and something that looks suspiciously like a weather pattern raining down onto the planet’s upper atmosphere. The gap between rings and clouds that once looked empty now brims with unseen chemistry.

Then there are the small worlds. The OSIRIS-REx mission showed us Bennu, a small near-Earth asteroid, not as a smooth rock, but as a loose rubble pile barely held together, its surface tossing pebbles back into space. Mars rovers have found pebbled streambeds and cracked mudstones where water once stood, and China’s Chang’e landers have scooped lunar soil that holds the story of ancient sunlight baked into tiny glassy beads.

| Mission / Observatory | Main Target | Type of Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| James Webb Space Telescope | Distant galaxies, exoplanets, nebulae | Early galaxies, star and planet formation details, exoplanet atmospheres |

| Hubble Space Telescope | Galaxies, clusters, planets | Long-term sky surveys, galaxy evolution, dark energy clues |

| Juno | Jupiter | Deep storms, polar cyclones, magnetic and gravity field maps |

| Parker Solar Probe | The Sun’s outer atmosphere | Solar wind origins, structure of solar corona, particle acceleration |

| ALMA | Cold gas and dust in space | Protoplanetary disks, molecular clouds, star-forming regions |

| Event Horizon Telescope | Supermassive black holes | First images of event-horizon-scale structures, black hole environments |

Listening to the Sun’s Hot Whisper

The Sun has always been too bright and too close for comfort. Look directly at it, and your eyes pay the price. Approach it with a spacecraft, and the heat begins to peel metal and electronics apart. Yet that’s exactly what the Parker Solar Probe has been doing: diving again and again into the corona, the Sun’s outer atmosphere that paradoxically grows hotter the farther it stretches from the surface.

Onboard instruments have flown through gusts and lulls of solar wind like a boat feeling out an invisible current. The probe’s sensors detect “switchbacks”—rapid reversals in the magnetic field that twist and snap like unseen whips. These flips, once just a curiosity, now look like a key part of the mechanism that heats and accelerates the solar wind streaming through the solar system.

In concert, the Solar Orbiter mission paints a wider portrait, capturing the first sharp views of the Sun’s mysterious poles and tracking how tiny eruptions on the surface stitch together into larger storms. Earth-based observatories add another layer, watching the Sun in different wavelengths, from radio to X-ray. Together, they’ve turned our star from a flat yellow disk into a dynamic, layered, boiling sphere whose moods we need to understand—not just for curiosity’s sake, but because those moods can knock out power grids, scramble satellites, and light up our skies with auroras that creep far toward the equator.

Galaxies in Their Infancy

Out beyond the comfort of our Milky Way, Webb has been pushing our gaze back in time, to when the first galaxies were forming. In those faint red smudges at the edge of visibility, astronomers expected to find chaotic, lumpy structures slowly coming together. Instead, we’re seeing something both messier and more organized than expected: bright, surprisingly mature-looking galaxies shining not long after the Big Bang, their light stretched into infrared by the expansion of space.

Some of these galaxies are simply too massive, too luminous, too soon, if our previous models are to be believed. Their existence is forcing astronomers to sharpen their equations and reconsider details of how quickly stars can ignite from primordial gas. At the same time, we’re seeing filaments of gas—cosmic rivers feeding these young cities of stars—more clearly than before, revealing a vast cosmic web where gravity and dark matter sculpt the bones of the universe.

In deep fields, where Webb stares for hours at a postage-stamp patch of sky, gravitational lenses—massive galaxy clusters in the foreground—stretch and magnify background galaxies into arcs and streaks. Those distortions, once visual oddities, are now tools: by modeling them carefully, astronomers can map invisible dark matter and pull details from galaxies that would otherwise be too faint to see at all.

Exoplanets: Reading Weather on Invisible Worlds

Perhaps the most quietly thrilling new details are coming from worlds we can’t even see as disks—exoplanets orbiting distant stars, revealed only by their shadows and subtle tugs. Using delicate measurements of starlight as these planets pass in front of their suns, Webb and other observatories are beginning to read their atmospheres like barcodes.

➡️ The streak-free window-cleaning method that still works flawlessly even in freezing temperatures

➡️ The quick and effective method to restore your TV screen to like-new condition

➡️ Thousands of passengers stranded in USA as Delta, American, JetBlue, Spirit and others cancel 470 and delay 4,946 flights, disrupting Atlanta, Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, Dallas, Miami, Orlando, Boston, Detroit, Fort Lauderdale and more

➡️ The sleep pattern that predicts alzheimer’s risk 15 years before symptoms

➡️ These zodiac signs are destined for major prosperity in 2026, according to astrological forecasts

➡️ The RSPCA urges anyone with robins in their garden to put out this simple kitchen staple to help birds cope right now

➡️ The RSPCA urges anyone with robins in their garden to put out this simple kitchen staple today

In these thin spectral lines—tiny missing pieces of light—scientists have found the signatures of water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, and clouds made of minerals and metals. Some hot Jupiters show hints of global winds ripping around them at thousands of kilometers per hour, with temperatures so high that rock could vaporize. Others, smaller and cooler, may have hazy skies more like a perpetual sunset.

We still don’t have a clean detection of life. But these atmospheric fingerprints are moving us closer to knowing what kinds of planets could be habitable at all, where chemistry might tilt from simple molecules to self-organizing systems. For now, every new detail—an unexpected gas, an odd temperature profile, an atmosphere stripped bare by its star—is a lesson in just how varied “planet” can be.

The Human Thread in a Nonhuman Universe

Behind each of these breathtaking details, there’s a quieter story: people hunched over monitors in control rooms, engineers calculating heat loads and fuel budgets, programmers writing code that will never see Earth again, and teams waiting nervously for a faint radio signal to confirm that a spacecraft has survived another encounter.

There’s the thrill in a lab when the first raw image arrives and someone, half-joking, half-serious, says, “This can’t be real.” There are years of wrangling over instrument designs, fierce debates about which targets deserve precious observation time, and the slow, careful work of making sense of terabytes of data. The details we marvel at—a spiral arm within a spiral arm, a jet of material from a black hole, a lightning flash on Jupiter’s night side—are the visible crest of a wave of human effort that often began decades earlier.

And yet, for all that effort, the universe still refuses to line up neatly with our expectations. Every new capability we build simply reveals a deeper strangeness. Galaxies form too fast. Black holes shine too bright. Small asteroids tumble and shed rocks in ways we didn’t anticipate. The Sun’s wind flips and twists. Exoplanet atmospheres refuse to match our tidy models.

That may be the best detail of all: the realization that we are not approaching the end of discovery but continually opening new rooms in an endlessly expanding house. The more eyes we place in space and on mountaintops, the richer, more tactile, more surprising the cosmos becomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are multiple spacecraft and observatories needed instead of just one powerful telescope?

No single instrument can see the full picture. Different telescopes observe different wavelengths (like infrared, X-ray, or radio), and each reveals distinct features. Spacecraft up close can measure particles, magnetic fields, and surfaces in detail, while distant observatories capture the big, structural context. Together, they offer a layered, more complete view of the universe.

What makes the James Webb Space Telescope so important?

Webb sees primarily in infrared, allowing it to peer through dust clouds that block visible light and to detect extremely distant, faint galaxies whose light has been stretched by cosmic expansion. Its large mirror and sensitive instruments make it ideal for studying the early universe, star and planet formation, and the atmospheres of exoplanets.

How do missions like Juno and Cassini change our understanding of giant planets?

They show that gas giants are far more complex than simple balls of gas. Juno’s gravity and magnetic measurements reveal deep, layered structures and gigantic storms that drill into Jupiter’s interior. Cassini’s close passes through Saturn’s rings and atmosphere uncovered real-time interactions, ring “rain,” and unexpected chemistry, reshaping our models of how such planets form and evolve.

Can we directly detect life with current space telescopes?

Current telescopes can’t directly confirm life, but they can look for atmospheric signatures that might hint at biological processes, such as specific combinations of gases that are hard to produce without life. The tools we have now are building a catalog of planetary environments and chemistry that will guide future, more specialized missions designed to search for biosignatures.

What is the most surprising recent discovery from these missions?

One standout surprise is the apparent abundance of massive, well-formed galaxies very early in cosmic history, revealed by Webb. Their existence challenges previous models of how quickly structures could form after the Big Bang, forcing astronomers to revisit assumptions about star formation, dark matter behavior, and the early universe’s timeline.