The first thing you notice is the silence. Not the stiff, school-trip silence of old museum visits, but a held-breath stillness—like the moment just before rain. A small group stands gathered in front of a glass case. Inside, a carved wooden figure, no taller than a child, leans forward mid-stride, as if it has been trying to walk out for the last hundred years. The curator, a woman in her early thirties with a braid down her back and a clipboard pressed to her chest, doesn’t begin with dates or dynasties. Instead, she asks, “Who do you think is missing this?”

The Quiet Revolution in the Glass Cases

For generations, museums told us their own version of history: the story of heroic explorers, noble collectors, and “lost” civilizations whose treasures were rescued into climate-controlled eternity. Visitors filed past cases and dioramas like pilgrims in a secular cathedral, rarely invited to wonder how these objects had traveled so far from home—or whether they had wanted to.

Now, something is shifting. Step into many museums today and the labels are different. Where we once saw neat phrases like “acquired in 1897,” we now see phrases that carry the weight of entire lifetimes: “taken during a military expedition,” “purchased under conditions of extreme imbalance,” “currently subject to repatriation claims.” The words land heavy and unsettling. They are meant to.

Behind these changes stands a new generation of curators. They grew up with social media and climate anxiety, with viral footage of toppled statues and hashtags demanding justice. They have inherited not just the keys to storerooms lined with thousands of objects, but also a dilemma: what does it mean to care for something that was never meant to be yours to keep?

In staff meetings, in late-night email threads, in whispered conversations over tea with visiting community elders, those curators are asking questions that once felt taboo. Why is this here? Who had to lose it for us to have it? And what would it actually mean to give it back?

The Storeroom Conversations

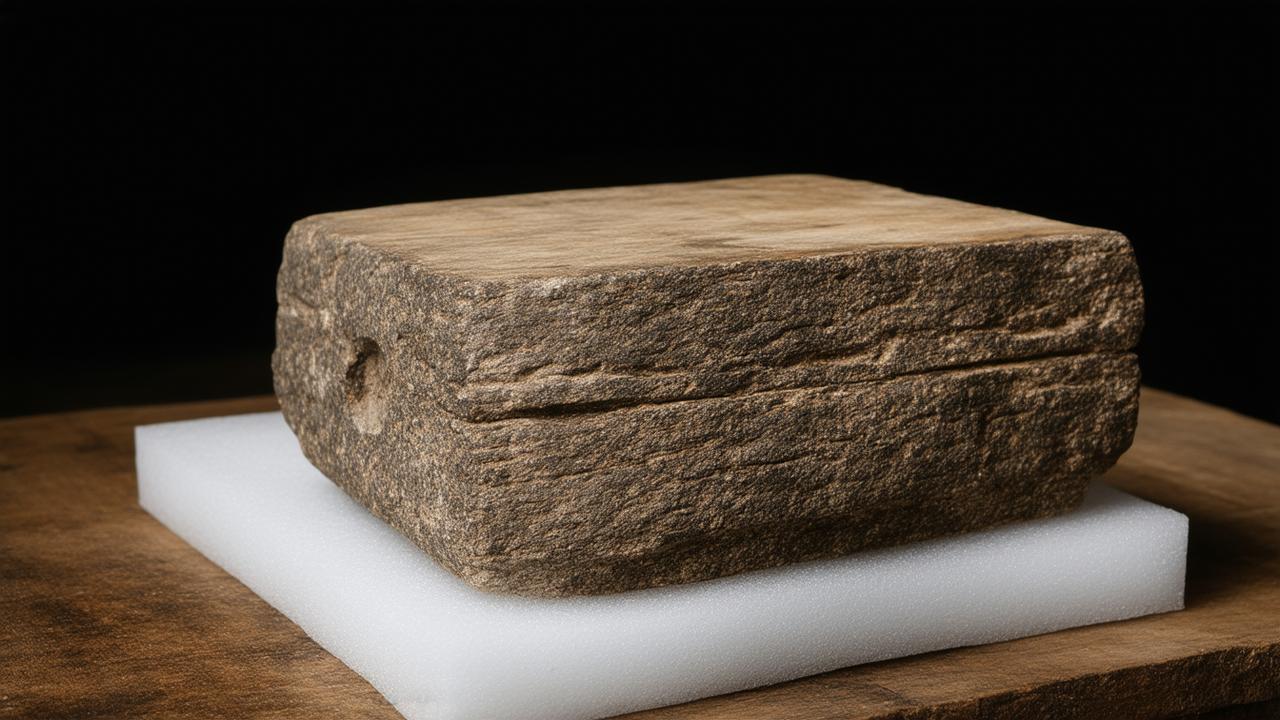

Deep in the bowels of the museum, past the polished marble and public-facing galleries, are the spaces most visitors never see. These storerooms smell faintly of dust and textile glue, temperature-controlled and windowless. Metal shelves stretch into the distance, lined with boxes labeled in careful handwriting: “Mask, West Africa, ca. 1900,” “Ceremonial bowl, Oceania, provenance unclear,” “Skull, unidentified, colonial era.”

This is where the real reckoning begins. A young curator—let’s call him Daniel—rolls a ladder down an aisle. On the shelf above his head sits a small crate with a faded sticker: “Specimen, ethnographic.” His notes tell him this came from an expedition led by a 19th-century anthropologist who traveled with missionaries and soldiers. The object itself, once he gently lifts it into the light, is a ceremonial headdress. Inside the lining, faint but visible, is a name handwritten in a language Daniel does not speak.

For the previous generation, this would have been a line item in a catalog. For Daniel, it’s something closer to a confession. That name is a clue: a person, a lineage, a community, perhaps still alive, still grieving a loss they were never asked to accept.

Conversations like this are now happening in museums around the world. Curators sit with maps and colonial records, with oral histories and community testimonies. They invite elders to walk through the aisles, to point out what doesn’t belong. Sometimes there is anger—sharp, decades-old anger that fills the room. Sometimes there is grief so quiet it’s almost unnoticeable, except for the way everyone’s shoulders sink the moment an object is recognized not as “collection” but as “relative.”

From Possession to Relationship

This new generation of curators is less interested in what a museum owns and more in what a museum is responsible to. Instead of thinking in terms of possession—“our collection”—they talk in terms of relationship—“our obligations.” In their vocabulary, an object might be an ancestor, a witness, a piece of a broken story waiting to be rewoven.

Repatriation used to be framed largely as a legal problem—who has the paperwork, who has the stronger claim. Now, for curators like Daniel, it’s also a question of ethics, of emotion, of ritual. What does it mean to hold onto a ceremonial object when the ceremony itself has been interrupted for a century? What happens when returning an item isn’t just about shipping it back, but about making space for the songs, dances, and languages that travel home with it?

These conversations are not neat. There is no universal checklist, no single timeline. But across continents, a pattern is emerging: younger curators are listening more and lecturing less. They are co-writing labels with community members, inviting Indigenous scholars into acquisition meetings, and reshaping the very idea of what a museum exists to do.

What the Numbers Don’t Show

In meeting rooms, printed reports summarize “ongoing repatriation initiatives.” They read like any institutional document: tidy, formal, strangely flat. But behind each bullet point is a story—a midnight phone call, a trembling hand holding an archival photograph, a flight ticket purchased not for a conference, but for a homecoming.

Consider a simplified snapshot of what some of this work can look like inside a hypothetical mid-sized museum:

| Area of Change | Traditional Approach | New Curatorial Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Object Labels | Minimal detail, focus on style and date | Full context, including how and why it was taken |

| Community Role | Occasional consultation | Shared decision-making and co-curation |

| Repatriation | Rare, often reactive to legal demands | Proactive, ongoing, ethically driven |

| Success Metrics | Visitor numbers, acquisition size | Quality of relationships, repaired histories |

These transformations aren’t as photogenic as a new wing or café renovation. They live in spreadsheets of provenance research, in hours spent cross-referencing shipping logs with diaries, in the difficult decision to say “no” to acquiring an item whose origins are murky. It’s slow work, the opposite of the quick-hit spectacle that once defined blockbuster exhibitions.

And yet, if you listen closely, you can hear something changing in the way visitors move through the space. They linger longer. They ask different questions. They are no longer just learning about the past; they are watching it being rewritten in real time.

Ethics in the Age of Return

In staff workshops, curators now discuss not only “best practices” but “harm reduction.” They ask: what harms did this institution help create in the past? Which harms is it still perpetuating by refusing to let go? They study colonial history alongside museum studies, reading not just the explorers’ journals but also the accounts of those whose homes were ransacked to fill European vitrines.

Ethics here isn’t a dry policy document pinned to a staff noticeboard. It’s a living set of questions: When is an exhibition an act of appreciation, and when is it an act of extraction? How do you honor the craftsmanship of an object while acknowledging the violence that delivered it into your care? Can the same gallery that once celebrated empire become a place where empire is openly, visibly challenged?

Sometimes, that ethical journey leads to a simple, difficult answer: this does not belong to us. Then the work becomes logistical, bureaucratic, occasionally political. Negotiations with ministries of culture. Legal agreements drafted and redrafted. Insurance details sorted. Quiet farewells whispered in storerooms as crates are sealed for their long trip home.

The New Language of Return

When an object is repatriated, the story used to end there—institution releases artifact, artifact goes home. Finished. But for this new generation of curators, return is not a period at the end of a sentence; it is a comma in a much longer, co-written narrative.

Some museums now travel with the pieces they once kept. Curators accompany returned objects to their communities, not as gatekeepers but as guests. They sit in community halls, in longhouses, under shade trees, listening as local historians and knowledge keepers reintroduce the object to its own people. Names long effaced by catalog numbers are spoken again. Songs are sung that have not been heard since the object left. The air is thick with incense, woodsmoke, or the bright salt of ocean wind.

In these moments, the old museum language—acquisition, inventory, asset—feels suddenly small. Another vocabulary rises to take its place: healing, reunion, ceremony. The curators, for their part, do not leave empty-handed. They bring back stories, recordings (when permitted), new understandings of what those objects mean far beyond any glass case could convey.

➡️ Nightlife venues are adjusting as sober socialising becomes a mainstream choice

➡️ Farmers are experimenting with regenerative grazing to rebuild soil after decades of depletion

➡️ Ocean chemistry data is pointing to faster acidification along sensitive marine habitats

➡️ Fashion labels are returning to wool as demand grows for durable climate smart fabrics

➡️ Archaeologists are returning to old shipwreck sites with new imaging technology

➡️ Households are embracing minimalism as rising costs challenge traditional consumer habits

➡️ Space startups are expanding beyond satellites as deep tech exports gain momentum

What a Museum Might Become

If you stand at the center of this change and pivot slowly, you can feel the institution itself turning. The museum is no longer just a warehouse of the world’s most beautiful things; it is becoming a site of moral repair, an archive of hard conversations, a place where colonial histories are not polished into heroics but exposed in all their fracture and grief.

The new curators are custodians of this turning. They are not perfect. They work inside systems that still prize fundraising galas and blockbuster shows. They face pushback from those who fear that repatriation will empty museums, or that admitting to past wrongs will diminish their prestige. But many of them have stopped seeing their job as defending the institution’s honor. Their loyalty is shifting outward: toward communities, toward ancestors, toward futures unburdened by stolen things.

And visitors are changing too. A schoolchild reads a label that says, “taken during a punitive expedition,” and asks a teacher, “What’s a punitive expedition?” That question travels home, to dinner tables, to history classes, to social feeds. The museum becomes not the final word on the past, but a starting point—an invitation to look again at everything we thought we knew.

A Future Built on Honest Display

On a quiet weekday afternoon, the young curator with the braid leads another small group to the wooden figure in the case. Her voice is steady, but her eyes give away something softer—an awareness that she is standing at a hinge in time. She gestures to the object and says, “We are currently working with community representatives on its possible return.” Then she steps back and lets the silence do the rest.

One day, perhaps, this case will be empty. The label will not try to hide that fact. It might read: “This object was returned to its community of origin in 2028. It lived here for 132 years. During that time, it helped us begin a conversation about repair.”

In that future gallery, visitors will stand in front of a void—the shape of an absence, clearly framed. They will not see less. They will see differently. The missing object will be a presence in its own way, a reminder that museums are not just places where things are kept, but places where decisions are made about what to hold, what to question, and what, at last, to let go.

Somewhere, far from the cold glass and controlled lighting, that wooden figure will stand again in warm air. The language spoken around it will not be the one printed on its old label. The stories told about it will not center on the museum that briefly kept it captive. Children will run past it, not knowing the word “repatriation,” but feeling, in the unbroken flow of songs and names, that it has always been theirs.

This is the quiet revolution in the making: a generation of curators learning that the deepest form of care is sometimes release, and that the most honest exhibition of history is not the one that hangs on to everything, but the one brave enough to admit that some things were never ours to display.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does “repatriation” mean in a museum context?

Repatriation is the process of returning cultural objects, human remains, or sacred items from museums or collections back to the communities or nations from which they were taken, often under colonial or coercive conditions.

Why are museums reconsidering colonial-era collections now?

A combination of factors—activism from source communities, public pressure, changing ethical standards, and a new generation of curators—has pushed museums to confront how many collections were acquired during periods of conquest, occupation, and extreme power imbalance.

Will repatriation empty museums?

No. While some high-profile objects may be returned, most museums hold far more material than they can ever display. Repatriation tends to reshape collections rather than erase them, and often leads to new forms of collaboration, loans, and co-curated exhibitions.

How do curators decide what should be returned?

Decisions usually involve provenance research (tracing an object’s history), legal frameworks, consultation with communities of origin, and ethical guidelines. Items taken by force, stolen, looted during conflict, or deeply sacred are often prioritized.

What role can visitors play in this process?

Visitors can read labels critically, ask questions about how objects were obtained, support institutions that are transparent about their histories, and listen to the perspectives of source communities. Public curiosity and pressure help create space for museums to change.