The first time I held a warm egg in my hand, it was still misted with the breath of the hen that laid it. I was standing in a small backyard in suburban Brisbane, barefoot in the grass still wet from last night’s storm, when my neighbour Marg called out, “Come ’round and grab some freshies, love!” She pressed a handful of eggs into my palms – some white as polished shells, some the colour of café latte. I remember frowning down at them, surprised. “So which ones are better?” I asked, almost without thinking. She laughed, a proper belly laugh that made the chooks cluck louder. “You’ll see,” she said, “when you’re older you’ll realise they’re all the bloody same.”

The story I carried for sixty years

I didn’t believe her. Or rather, I didn’t quite want to. For sixty years I’d carried a mental list of “truths” about eggs that had calcified in my head like old yolks in a forgotten frying pan. Brown eggs are healthier. White eggs are factory-farm rubbish. Brown eggs must be free-range. White eggs crack more easily. Brown yolks are richer. White eggs are cheaper because they’re worse. Ask around at any weekend market from Fremantle to the Sunshine Coast and you’ll hear variations of this folklore traded between stalls along with sourdough and spinach.

It’s the kind of certainty you inherit, really. I grew up with my mum reaching for the brown carton, almost on autopilot, because “they’re more natural.” At school, the tuckshop sandwiches were made with pale, white-shelled eggs no one trusted. “Cheap bulk stuff,” the parents would mutter. Supermarkets piled in behind the myth: brown cartons decorated with rustic fonts and a token windmill, white eggs dressed in clinical blues and whites that whispered “industrial.” Nobody had actually explained the difference; we just… knew.

Except, as I finally learned – properly learned – at sixty, we didn’t know at all.

The day a chicken farmer ruined my favourite myth

The myth finally cracked one windy afternoon on a farm tour in northern New South Wales. I’d tagged along with a friend who writes about sustainable food. The place was classic Australian farmhouse: rusting corrugated iron sheds, a thick stand of gums along the creek, and a scatter of red dust that clung to your boots and wouldn’t let go.

The farmer, a stocky woman named Elise in a wide-brim hat that meant business, led us towards a paddock buzzing with life. Hens flowed around our ankles, a mixed confetti of colours – honey gold, deep rust, snow white – all busy, all chatty. Their clucks rolled around us like casual gossip. A few pecked at my shoelaces. It was the opposite of the silent, sterile image of egg production I’d held in my head.

Near the fence, she’d set up trays of eggs for us to see. Brown, white, some in soft blue and green, even a couple marbled with faint freckles. It looked like a designer’s mood board for “breakfast in the country.” I went straight for the question that had lived in my throat for years.

“So,” I asked, “which ones are actually better for you – the brown or the white?”

She looked at me like she’d been waiting for that exact sentence her entire career.

“Neither,” she said. “They’re just different coloured shells. That’s it.”

The science hidden in plain sight

If that answer feels too simple, that’s because the truth often is. The colour of an eggshell is determined almost entirely by the breed – and genetics – of the hen. White-feathered hens with white ear lobes (yes, chickens have ear lobes) tend to lay white eggs. Brown-feathered hens with red ear lobes tend to lay brown eggs. Some breeds lay blue or speckled eggs. It’s like hair colour in humans: interesting, visible, and mostly irrelevant to what’s happening on the inside.

The shells themselves are made of the same thing: calcium carbonate. Underneath the coloured coating, a white egg and a brown egg are biologically the same. You can even scratch off a tiny flake of colour from a brown shell and see the white underneath. The pigment that makes brown eggs brown – protoporphyrin – is simply painted on in the last stages before the egg is laid. It doesn’t seep into the egg white or yolk. It doesn’t add extra iron or “earthiness” or anything remotely mystical.

What actually changes the nutrition – the flavour, even the colour of the yolk – has almost nothing to do with the shell. It has everything to do with the hen’s life: what she eats, how much she moves, whether she sees the sun, how stressed she is. Feed a white-egg-laying hen a rich, varied diet with access to pasture, and she’ll give you eggs every bit as flavourful and nutrient-dense as her brown-egg sisters. Put a brown-egg hen in a cramped shed on bland feed, and her eggs will reflect that too.

In Australia, we often mistake packaging and price for proof. Brown eggs in cardboard cartons with friendly drawings of chooks in fields feel more wholesome. White eggs in glossy plastic with sterile branding feel, well, industrial. But that emotional story sits in the marketing, not in the shell.

The quiet realities of Australian egg cartons

Back home, I started reading cartons like crime novels. Standing under the humming lights of a Coles in suburban Melbourne, I realised I’d walked past the truth for decades. The shell colour wasn’t even listed on half the boxes, not in the legal text that actually matters. What did matter – but was written in small, easily ignored type – were the real differences: cage, barn-laid, free-range, organic. And, critically, the stocking density.

In Australia, “free-range” by law can still mean up to 10,000 hens per hectare. Some ethical producers go much lower – 1,500 hens per hectare or less – but you’ll usually only notice that if you actually look. Most of us don’t. We grab the nicest-looking carton, often brown and cheerfully illustrated, and assume we’ve made the “good” choice.

I started asking more questions at farmers’ markets. “Do your hens get outside every day?” “What’s in their feed?” “Do you trim beaks?” And then, almost sheepishly, “Do they lay white or brown eggs?” More often than not, the farmers would shrug. “Bit of both, depending on the girls we’ve got,” one told me, handing me a carton mottled with brown, cream, and chalk-white. “Same chookyard. Same sun. Same grass. Same feed. Different feathers, that’s all.”

To make the comparison easier, I started keeping notes at home – a small, completely unscientific kitchen experiment that delighted my inner nerd. Same pan, same cooking time, different eggs.

| Egg Type | Shell Colour | Hen Conditions (Observed/Labelled) | Flavour & Yolk Colour (My Experience) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supermarket cage eggs | Mostly white | Caged, indoor, standard feed | Mild flavour, pale to mid-yellow yolk |

| Supermarket “free-range” (high density) | Mostly brown | Outdoor access, but crowded | Slightly richer flavour, mid-yellow yolk |

| Low-density free-range farm eggs | Mix of white & brown | Pasture access, varied feed, active hens | Full flavour, deep yellow to orange yolk |

| Backyard chook eggs | Random mix | Scraps, bugs, grass, plenty of sun | Varied but often intense flavour, rich yolks |

The pattern was undeniable: shell colour told me nothing. Lifestyle told me nearly everything.

Brown costs more – but why?

One puzzle remained: if brown and white eggs are essentially the same, why are brown eggs often more expensive in Aussie supermarkets? The answer, as Elise and several other farmers patiently explained to me over the months that followed, lies not in mystique but in maths.

Many brown-egg-laying breeds are a touch larger and can cost slightly more to raise. Feed, housing and lower stocking densities for certain “premium” brands also add to the price. Historically, white-egg-laying breeds became popular in more intensive systems because they convert feed very efficiently. Brown eggs, meanwhile, started to be associated with “old-fashioned” farmyard breeds and more traditional, less-intensive setups, even if that wasn’t always true in practice.

Marketers leaned into that perception. Brown shells looked rustic and “from the farm,” so they were nudged into the premium end of the shelf. White eggs slid quietly into the budget lane. Over time, we began to equate colour with quality, even as the real differences were printed clearly – and mostly ignored – on the side of the carton.

The irony? In some countries, white eggs are the premium choice. In others, blue or speckled eggs fetch the highest prices at market. What counts as “natural” turns out to be whatever colour your culture has quietly fallen in love with.

➡️ Psychologists share the sentence that lets you decline any offer politely and still look confident

➡️ According to astrological forecasts, these zodiac signs are destined for major prosperity in 2026

➡️ Goodbye kitchen islands: the 2026 trend replacing them is more practical, more elegant, and already transforming modern homes

➡️ By planting over 1 billion trees since the 1990s, China has slowed desert expansion and restored degraded land

➡️ Boiling rosemary is a simple home tip I learned from my grandmother, and it can completely transform the atmosphere of your home

➡️ A Nobel Prize–winning physicist says Elon Musk and Bill Gates are right about the future : we’ll have far more free time: but we may no longer have jobs

➡️ Goodbye Kitchen Islands : their 2026 Replacement Is A More Practical And Elegant Trend

The lesson tucked inside a humble omelette

The turning point for me arrived in the shape of a very simple lunch. I’d come home from the markets with a carton of mixed eggs – brown, white, a couple so cream-coloured they almost glowed. They’d all come from the same small farm on the outskirts of town. Same hens, same pasture. The farmer had simply shrugged and said, “Whatever they lay, they lay.”

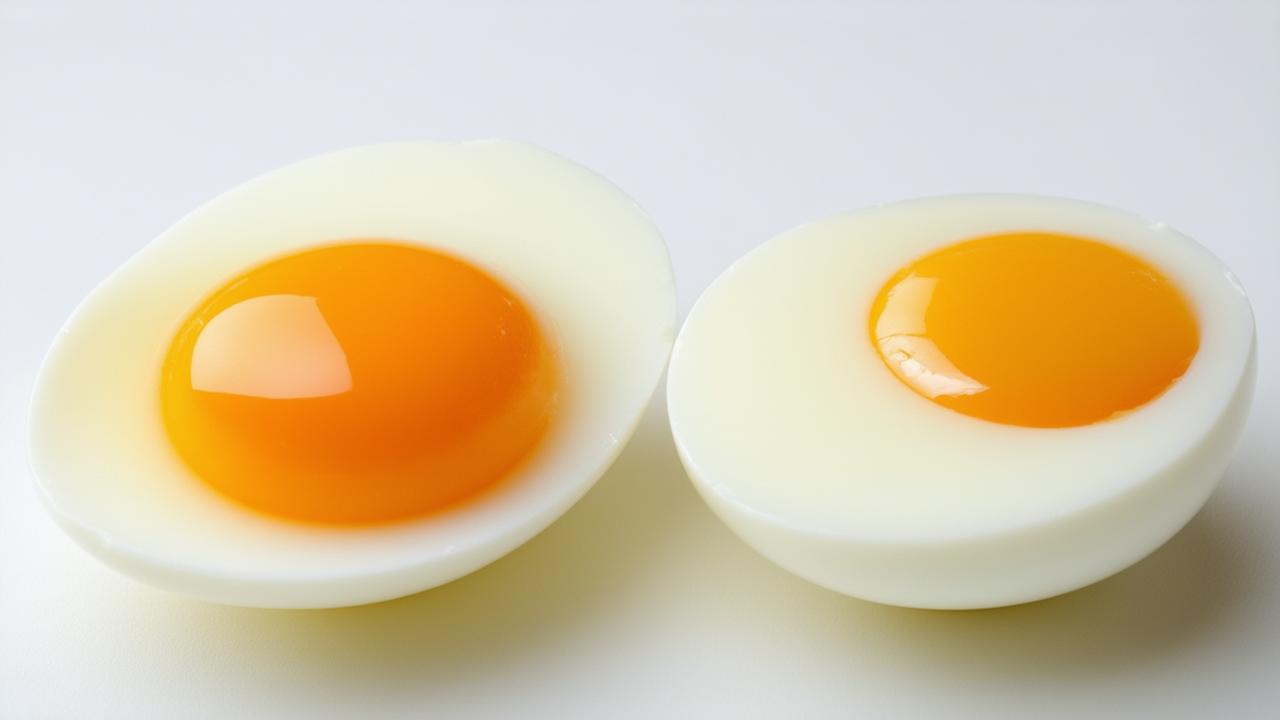

Curious, I cracked a white egg and a brown egg into the same bowl. Same yolk colour. Same viscosity of whites. They whisked together without protest, folding into a small cloud of golden foam. In the pan, they puffed into silky curds that smelled faintly of grass and rain, the way truly fresh eggs do. Sitting at my kitchen table, watching the jacarandas shimmy in the wind outside the window, I took a bite.

If you’d asked me in that moment which shell it came from, I couldn’t have told you. All I could tell was that the hen had been well-fed and well-treated. The flavour carried that quiet, distinctive richness you simply don’t get from a life spent under fluorescent lights and steel.

I realised then that I’d allowed a lazy story – brown good, white bad – to stand in for paying real attention. I’d reached for the comfortable myth instead of reading the smaller print or, better yet, talking to the people whose days revolve around caring for those birds.

What I wish I’d known decades earlier

If I could go back and whisper some advice into my younger self’s ear as she stood in that long supermarket aisle, it would be this:

- Don’t judge an egg by its shell. White, brown, blue, speckled – they’re all just different wrappers on the same core design.

- Read the stocking density and housing type, not just the big-font promises on the front of the carton.

- When you can, talk to the person who collects the eggs. Ask what the hens eat, where they spend their days, how much space they have.

- Let your senses guide you. Crack the egg. Notice the yolk colour, the firmness of the white, the aroma in the pan.

- Remember that every egg is a kind of quiet biography of a bird’s life – not her feather colour, but her freedom, her feed, her stress, her sun.

At sixty, I’ve finally relaxed around the egg aisle. I no longer lunge automatically for the brown carton. Sometimes I buy a box of snowy white eggs from a small producer whose farm I’ve walked. Sometimes I come home with a rainbow from a friend’s backyard, like edible Easter eggs nestled in reused cardboard. What matters to me now is the story behind them – the human and the hen, not the shell.

And every time I crack an egg into a pan and watch it bloom in the heat, I think of my neighbour Marg and her chuckling certainty. “You’ll see,” she said. It took me sixty years, but I finally do.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are brown eggs more nutritious than white eggs?

No. Brown and white eggs have virtually identical nutritional profiles when laid by hens with similar diets and living conditions. Any difference in taste or nutrient content comes from how the hen was raised and what she was fed, not the shell colour.

Do brown eggs taste better?

Why are brown eggs often more expensive in Australia?

Brown eggs are frequently associated with certain breeds and farming systems that cost more to run, and marketers position them as a “premium” product. The higher price is usually about production style and branding, not inherent superiority of the egg itself.

Is a darker yolk always healthier?

Not always. Darker yolks often come from hens eating more pigmented feeds such as greens, maize, or marigold, which can increase some nutrients. But yolk colour can also be enhanced with certain feed additives. It’s one clue, not proof on its own.

What should I look for on Australian egg cartons?

Check the housing system (cage, barn, free-range, organic), and if listed, the stocking density (hens per hectare). Look for lower numbers and clearer information about outdoor access. Shell colour is purely cosmetic and doesn’t need to factor into your decision.

Are white eggs more likely to be from caged hens?

Not necessarily. While many intensive systems historically used white-egg breeds, plenty of ethical and free-range farmers in Australia keep white-egg-laying hens as well. You need to read the housing details on the carton or talk to the producer, rather than judging by colour.

Can I mix white and brown eggs in cooking or baking?

Absolutely. They perform the same in recipes. As long as they’re fresh and of similar size, you can swap or mix white and brown eggs freely in baking, scrambling, poaching, or any other cooking method.