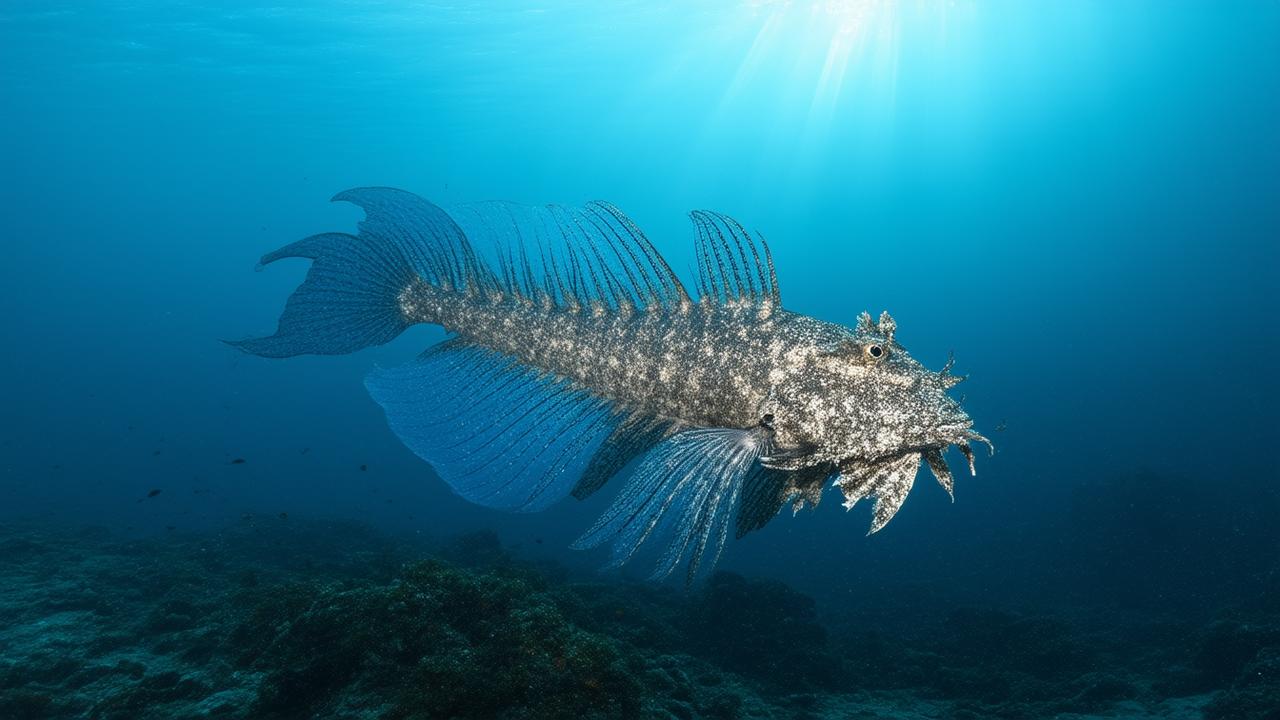

The first thing they noticed was the colour—an impossible midnight blue rising out of the black. Twenty-seven metres down, in the warm, inky waters off North Sulawesi, a small beam of torchlight caught a shape that simply did not belong to our age. It moved with a slow, regal twist of its fins, not quite fish, not quite something you could name at all. Later that night, back on the rocking dive boat, someone whispered the word for what they had just seen: coelacanth. A living fossil. And for the first time, a French dive team had captured rare, crystal-clear images of this prehistoric icon in Indonesian waters.

A Face from Deep Time

Imagine hovering mid-water, your body wrapped in the press of the sea, heart already a little fast from the depth. The bottom is still a darker smear far beneath your fins. Currents tug at your mask strap. Your torch beam, thin and shaky, pencils through particles of marine snow—tiny flecks of life and death drifting toward the abyss.

Then, at the edge of the light, something steps out of time itself.

The coelacanth does not rush. It rotates into view, its body a thick, scaled cylinder studded with white blotches like old stars in a night sky. The fins—limb-like, muscular, jointed—do not flap as a tuna’s would. They row. They walk through the water with an eerily deliberate rhythm. Its eyes, glassy and pale in the beam, seem detached, as if contemplating something far older than you, your tank, or even your species.

For decades, we have called the coelacanth a living fossil—an animal whose lineage stretches back more than 400 million years, to an era when the first forests were just greening the land and Australia was still fused to Antarctica. For a long time, scientists believed coelacanths had vanished along with the dinosaurs, leaving only stone impressions in the world’s museums. Then, in 1938, a trawler off South Africa hauled up an impossible catch. The story of the “Lazarus fish” began there.

The Night the Ocean Gave Up Its Secret

The French dive team had not gone to Indonesia expecting a miracle. Their plan was ambitious, certainly: deep twilight plunges along steep drop-offs, exploring caverns and overhangs where large pelagics sometimes cruise. The Indonesian archipelago is already known to Australians as a second-home playground—Bali holidays, Lombok surf trips, Komodo liveaboards—but the divers were operating beyond the reach of most recreational visitors: extreme-depth technical dives, meticulously planned, minutes measured in gas consumption and decompression stops.

On the day of the sighting, the sea rolled with that lazy, deceptive calm that hides strong currents below. The divers descended past the busy reef slope, past the broccoli forests of Acropora and whirling anthias, into the muted, cobalt quiet below thirty metres. Here the reef thinned into rock, ledges, and shadowed pockets. The last of the sunlight fell away into a twilight hush, pierced only by the beams of their torches.

They were not hunting myths. But myths, occasionally, hunt us.

Out of a wide crevice in the rock wall, a dark mass drifted into their path. For a heartbeat, it was just another large, unknown shape in the blue—a grouper, maybe. Then the outline sharpened: the distinctive three-lobed tail, the stout body, the odd placement of fins like limbs sprouting from a torso. Camera housings swung around. Fingers tightened on shutter buttons.

The coelacanth turned, unbothered by the cloud of bubbles erupting from the stunned divers’ regulators. It seemed almost languid, pulsing its paired fins in that unmistakable, four-beat gait that once may have foreshadowed the first steps onto land. Lights flared. Strobes flashed. For a few breathless minutes, deep time posed for the lens.

What Exactly Is a “Living Fossil”?

The phrase “living fossil” gets thrown around too easily. In the Australian bush, we sometimes hear it applied to everything from lungfish to ancient cycads. But the coelacanth is one of the rare creatures that truly earns the label.

Coelacanths belong to an ancient lineage of lobe-finned fishes—cousins to the ancestors that eventually crawled onto land and gave rise to all amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, including us. For over 60 million years, they seemingly vanished from the fossil record. When that first modern specimen surfaced in South Africa, its anatomy was a time capsule: a hinged skull, thick cosmoid scales, and limb-like fins with internal bones reminiscent of primitive legs.

Genetic studies since have revealed that coelacanths have changed remarkably little over vast stretches of evolutionary time. They are not “unchanged” (nothing living is), but their body plan has proven astonishingly durable. They cruise steep volcanic slopes, caves, and submarine canyons, living slow, long lives—up to a century, some estimates suggest—breeding rarely, moving methodically, sipping oxygen in a low-metabolism existence that seems perfectly tuned to the deep’s stillness.

Indonesian Waters, Global Wonder

Australians know Indonesia as a neighbour, a surf trip, a cheap flight north. But beneath those familiar flight paths lies one of the richest marine crossroads on the planet: the Coral Triangle. Stretching across parts of Indonesia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and beyond, this region is the beating biodiversity heart of the Indo-Pacific. Many of the reef fish we see on the Great Barrier Reef trace their origins, or at least their genetic mixing grounds, to this region.

Coelacanths have long been associated more with the western Indian Ocean—Comoros, Madagascar, South Africa. That changed dramatically in 1997, when a coelacanth was discovered in a market in Manado, North Sulawesi. A second species, Latimeria menadoensis, was described from these Indonesian waters. Unlike their African cousins, these Indonesian coelacanths lurk in deep volcanic habitats, hiding in caves during the day, emerging at night to hunt.

The French divers’ new images, taken at recreationally extreme but still diver-accessible depths, reinforce something quietly astonishing: in relatively close proximity to where Australians holiday each winter, an animal from the Devonian still swims, very much alive. The idea that you could wake in a Bali guesthouse, sip a flat white between scooter horns, then fly a short hop north to waters where coelacanths patrol the drop-offs makes the familiar map of our region feel suddenly wilder, less finished.

Why These Photos Matter

Rare as they are, coelacanths are not just curiosities. Each new observation adds a piece to a slowly assembling puzzle—one that matters for conservation, science, and even how we tell stories about life on Earth.

| Aspect | Why the New Images Are Important |

|---|---|

| Behaviour | High-quality footage helps scientists study how coelacanths swim, hunt, and use their fins in three dimensions. |

| Habitat | Precise depth, temperature, and terrain details refine our understanding of the micro-habitats they prefer. |

| Distribution | Each confirmed sighting helps map the species’ range and highlights new areas needing protection. |

| Public Awareness | Compelling, shareable images turn an obscure deep-sea fish into a powerful ambassador for ocean conservation. |

For Australian scientists, collaborations with Indonesian researchers around finds like this deepen an already vital partnership. Our own marine parks on the north-west shelf, the Timor Sea, and the Coral Sea are influenced by the same currents that wash these coelacanth caves. Understanding one part of this system sharpens our picture of the whole.

Echoes for Australia’s Own “Ancient Ones”

For an Australian reader, there’s something familiar about the coelacanth story. It rhymes with our own ancient survivors: Queensland lungfish gliding through dark freshwater billabongs; the Wollemi pine discovered in a Blue Mountains gorge after 90 million years presumed gone; the enigmatic goblin sharks of our deep continental slopes; even the short-beaked echidna, spiny relic of a lineage that once shared the earth with dinosaurs.

The coelacanth, though foreign, feels like kin to these creatures. Each reminds us that evolution does not move in a straight line of “progress.” Sometimes, a body plan just works. It persists through mass extinctions, drifting continents, climate swings. The “living fossil” idea, while a bit misleading scientifically, resonates emotionally because it collapses vast geologic time into something we can look in the eye—or, in the case of those French divers, something that can look quietly back at us from the dark.

There’s a deeper lesson here that reaches beyond biology. First Nations Australians have maintained continuous cultural and ecological knowledge for tens of thousands of years. Their stories, songlines, and seasonal calendars hold a different kind of fossil record—of relationships with places, species, and cycles. When a coelacanth appears on a diver’s camera, it is also a reminder to listen harder to the ancient knowledge systems that have always understood the deep entanglement of life.

Tourists, Depth, and Responsibility

It is tempting, from a comfy couch in Brisbane or Perth, to turn this story into a new bucket-list dream: “Dive with living fossils in Indonesia!” But the reality beneath the romance is sobering.

➡️ These zodiac signs are destined for major prosperity in 2026, according to astrological forecasts

➡️ The RSPCA urges anyone with robins in their garden to put out this simple kitchen staple to help birds cope right now

➡️ The RSPCA urges anyone with robins in their garden to put out this simple kitchen staple today

➡️ What you see is not a ship : at 385 metres long, Havfarm is the world’s largest offshore salmon farm

➡️ “I used to multitask constantly,” this habit helped me stop without effort

➡️ Workers in this role often earn more by becoming specialists rather than managers

➡️ If you want a happier life after 60 be honest with yourself and erase these 6 habits

Coelacanths live close to the physiological limits of their design. They favour deep, cool, stable environments. Sudden bursts of exertion—such as being chased, hooked, or netted—can be deadly. Their reproduction is glacial: long gestation, few offspring, slow growth. They are evolution’s slow burn, not built for an age of speed and extraction.

Most of the French team’s skill lay in their restraint. They observed, documented, and withdrew. They did not push closer for the perfect shot. They managed their lights carefully to minimise stress. They shared their findings not as sensational tourism bait, but as data and story for scientists and the public alike.

For Australians who travel north to dive—whether on liveaboards in Raja Ampat or muck dives in Lembeh Strait—this kind of ethics is increasingly non-negotiable. If we are to revel in the riches of our shared ocean, we must also insist on operators and practices that put the animals’ needs before our thrill. That means respecting depth limits, staying off fragile substrate, controlling flash use, and supporting marine protected areas that give beings like the coelacanth a buffer from our presence.

What the Coelacanth Tells Us About the Future

Maybe the strangest thing about the coelacanth is not that it survived the age of dinosaurs, but that it has also survived us—so far. We have trawled, mined, and plastic-wrapped our seas, and still, in a volcanic fold off Indonesia, an animal whose ancestors swam before the first kangaroos appeared still pulses its fins in the dark.

This survival, though, is precarious. Deep-sea mining prospects loom over parts of the Indo-Pacific. Climate change is shifting temperature bands downward, altering the subtle structure of deeper layers. Even noise pollution from ship traffic can penetrate the depths. The coelacanth may be hardy across geologic time, but it is not invincible against rapid, human-driven shifts.

For those of us in Australia, the story offers both a warning and an invitation.

- A warning that the deep is not an untouched “elsewhere” we can afford to ignore. Our choices—energy policies, plastic use, fishing practices—ripple down the water column.

- An invitation to expand our circle of care beyond the photogenic shallow reefs we snorkel over on holiday. To imagine a conservation ethic big enough to include creatures we will never personally meet.

When those French divers surfaced, decompressing slowly in the blue layers between the coelacanth and the sun, they carried with them more than memory cards. They carried fresh proof that the world we inhabit is layered with vast, unseen ages, still moving, still breathing. The living fossil is no museum exhibit. It is out there tonight, somewhere below the flight paths and resort lights, gliding along a rock wall in the Indonesian dark.

In a century that often feels defined by loss—of coral cover, of species, of certainty—this knowledge is unexpectedly hopeful. If a lineage can thread its way from the Devonian to the Anthropocene, perhaps our own story is not yet fixed. The coelacanth does not promise a happy ending. It does something quieter: it insists that the past is not gone, that the future is not entirely written, and that our choices in this narrow slice of time still matter immensely, for everything that swims, crawls, or walks the ancient paths of this shared planet.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are coelacanths dangerous to divers?

No. Coelacanths are not considered dangerous to humans. They are slow-moving, deep-dwelling fish that tend to avoid interaction. The primary concern is not what they might do to us, but what our presence might do to them—stress, disturbance, or accidental capture.

Can recreational divers from Australia see coelacanths in the wild?

It is extremely unlikely. Coelacanths typically live at depths beyond standard recreational limits and in very specific habitats. The rare encounters, like the French divers’ sighting, involve advanced technical training, careful planning, and a strong scientific or documentation purpose rather than tourism.

Why are they called “living fossils” if evolution never stops?

The term “living fossil” is informal. It refers to species that closely resemble their ancient fossil relatives and have changed relatively little in body plan over long periods. Coelacanths are still evolving at the genetic level, but their overall form remains strikingly similar to fossil specimens hundreds of millions of years old.

Do coelacanths live near Australia?

Known coelacanth populations occur off East Africa and in parts of Indonesia, including North Sulawesi. While these Indonesian habitats are within the broader Indo-Pacific region we share, coelacanths have not been recorded in Australian waters to date.

How does this discovery affect conservation in our region?

Each new confirmed sighting reinforces the importance of protecting deep habitats, not just shallow reefs. For Australia and Indonesia, it highlights the need for cooperative marine management, careful regulation of deep-sea industries, and support for research that maps and safeguards critical habitats, including those of rare, ancient species like the coelacanth.