The first time you lose a tooth as a child, there’s a kind of magic to it. A tiny gap in your smile, a visit from the tooth fairy, the quiet reassurance that something new will grow in its place. But somewhere along the line—usually in your late teens—that magic stops. Adult teeth arrive, and that’s it. No more replacements, no more second chances. Or at least, that’s what we’ve always believed. Now, in a series of quietly revolutionary labs around the world, researchers are beginning to tell a different story—one where our bodies might hold hidden reserves of regenerative power, and where a damaged tooth, or even a broken bone, may not be an ending but the start of a remarkable repair.

A Hidden Reserve Inside Our Teeth

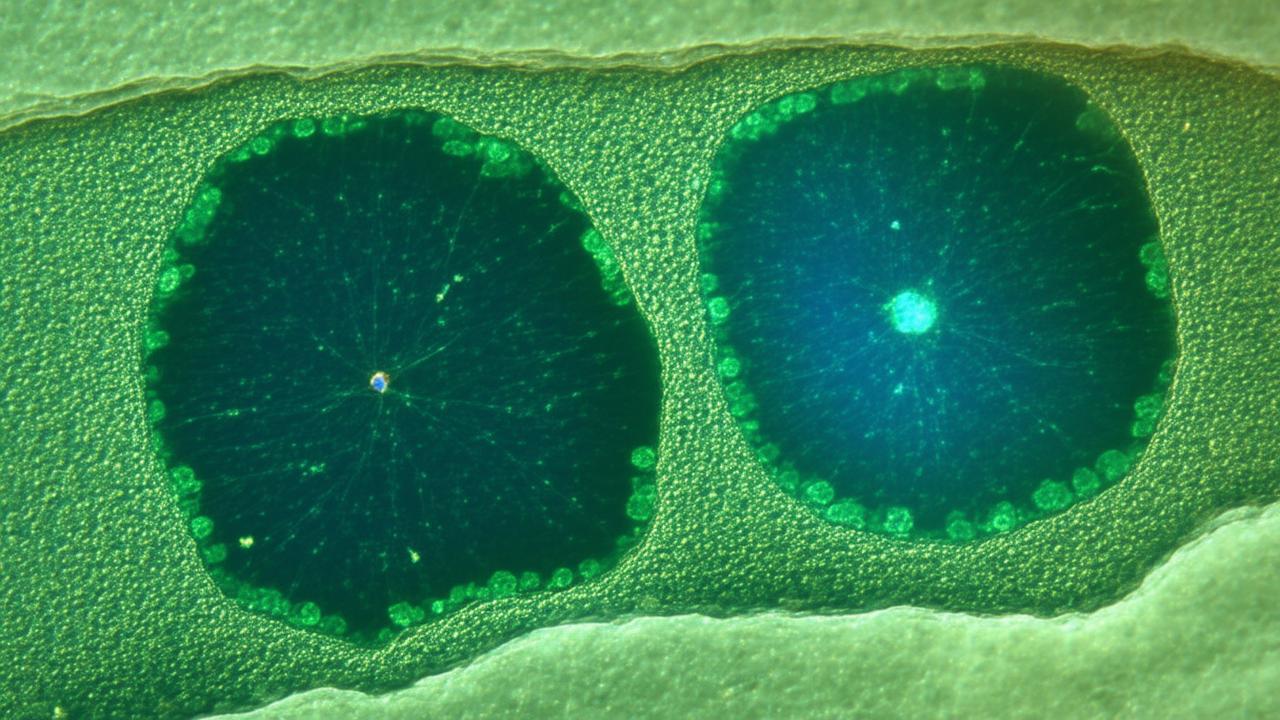

It begins deep inside the mouth, far from the glossy enamel we see in the mirror. Strip away that hard outer shell, past the dentin that cushions it, and you arrive in a soft, pulsing space: the dental pulp. This is where blood vessels and nerves thread their way through microscopic channels, where pain signals are born, where the tooth stays alive.

For years, scientists have quietly suspected that dental pulp might shelter a special kind of stem cell—adult stem cells that haven’t forgotten how to become many things. They are not the wild, early embryonic stem cells that spark debates and headlines, but rather something humbler, subtler, and yet still astonishing: a small population of cells that retain the power to regenerate tissues.

Recently, a team of researchers has gone further than suspicion. They’ve isolated a specific type of adult stem cell inside human teeth and found that it has a remarkable talent: it can not only help regenerate tooth structures but also play a role in repairing bone. These cells are like a quiet workforce waiting in the wings, ready to be guided by the right signals—a kind of built-in repair toolkit we’ve only just discovered how to open.

The Moment the Cells Reveal Their Power

In the lab, the discovery doesn’t start with drama. It starts with something very ordinary: an extracted wisdom tooth, a discarded molar, a tooth removed because of overcrowding. To most of us, these are medical leftovers, destined for a biohazard bin. To a stem cell researcher, they’re a treasure chest.

Under the bright, patient gaze of the microscope, tiny fragments of the inner pulp are carefully dissected, rinsed, placed into culture dishes filled with nutrient-rich media. Then comes the waiting. Days pass. The once still fragments begin to change. Cells creep out from the tissue, stretching across the glass like cautious explorers testing an unfamiliar landscape.

When the scientists look closer, they notice that these cells behave differently from ordinary pulp cells. They divide steadily but not chaotically. They respond to subtle chemical signals. When given the right cues, they don’t just multiply—they transform. They begin to express markers typical of mesenchymal stem cells, a versatile type known for giving rise to bone, cartilage, and fat tissues. These particular dental stem cells, the team realizes, are exceptionally good at forming the kinds of solid, structural tissues that teeth and bones rely on.

What Makes These Stem Cells So Special?

Not all stem cells are created equal. Some are highly specialized, fixed in their roles. Others can become almost anything. The newly identified dental-derived stem cells sit somewhere in between—powerful, yet more controllable, and crucially, already part of the adult body.

In controlled experiments, the cells are coaxed with molecular “instructions.” When exposed to specific growth factors, they start laying down minerals, forming tiny nodules that resemble early bone. In other conditions, they generate structures similar to dentin, the inner material of teeth that supports enamel. Their versatility catches the researchers’ attention. Here is an adult stem cell that can cross boundaries: from tooth to bone, from repair to regeneration.

Imagine a fractured jawbone that refuses to heal cleanly, or a critical bone defect caused by trauma. Now imagine a graft not taken from the patient’s own hip or leg—a painful, invasive procedure—but grown instead from their dental stem cells, seeded onto a biocompatible scaffold, and guided to become fully functional bone.

From Tooth Fairy Myths to Regenerative Medicine

There’s an almost poetic symmetry in the idea that the place we associate with childhood tooth loss could hold the key to tooth regrowth in adults. Yet the science unfolding in sterile labs is far from fantasy.

In animal studies, when these adult dental stem cells are transplanted into areas of bone damage, they integrate into the tissue and start doing exactly what you would hope: they contribute to new bone formation. Microscopic imaging reveals that the newly formed bone is not just a rough patch of calcified matter; it’s structured, vascularized, and dynamic. It behaves like bone, responds to stress like bone, heals like bone.

In parallel experiments, scientists are exploring how to persuade the same cells to rebuild parts of a damaged tooth. They can’t yet conjure an entire perfectly shaped molar, but they can stimulate the cells to rebuild dentin-like structures and support the vitality of the remaining tooth. It’s a careful symphony of signals—growth factors, scaffolds, electrical and mechanical cues—each one nudging the stem cells a little closer to the desired fate.

How Dental Stem Cells Compare to Other Stem Cells

Modern regenerative medicine already has a cast of familiar characters: bone marrow stem cells, fat-derived stem cells, and more experimental induced pluripotent stem cells (reprogrammed from ordinary adult cells). So where do these newly highlighted dental stem cells fit?

In many ways, they have a sweet spot of advantages. They are relatively easy to obtain—from teeth that are often removed anyway, without the need for drilling into bone or harvesting fat. They appear to be highly efficient at making mineralized tissues. And early studies suggest they may carry a lower risk of forming unwanted tissue types when compared to some other stem cell sources.

To put it clearly, it’s not that dental stem cells are “better” than all others. It’s that they may be uniquely well suited for repairing exactly the kinds of structures they came from: teeth, jawbones, parts of the face and skull. They are local specialists, waiting in the wings of the very tissues they are best at rebuilding.

| Stem Cell Source | Typical Harvest Method | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|

| Dental pulp (adult teeth) | Extracted teeth, minimally invasive | Tooth tissue, jawbone, facial bone repair |

| Bone marrow | Needle aspiration from hip or long bones | Bone, blood cells, immune-related therapies |

| Adipose (fat) tissue | Liposuction or small surgical removal | Soft tissue repair, cosmetic and reconstructive uses |

| Induced pluripotent cells | Lab reprogramming of adult cells | Experimental therapies, disease modeling |

The Future Dentist’s Toolkit

Step a few years into the future and picture a different kind of dental visit. You sit in the familiar reclining chair, the light still bright, the tools still gleaming on a tray. But the conversation sounds changed.

Instead of hearing “We’ll need to remove this tooth and replace it with an implant,” you hear something more tentative, more hopeful: “We can try a regenerative procedure. We’ll use your own stem cells to help this tooth rebuild from the inside.”

In this imagined clinic, a tooth that would once have been condemned to extraction becomes a candidate for rescue. A sample of pulp tissue is collected, stem cells isolated and expanded, then guided back into the tooth or surrounding bone using bioengineered scaffolds. Over the following months, instead of watching a gap appear, you watch the repaired tooth settle back into its role, stronger and more alive than anyone would have thought possible a generation earlier.

This isn’t science fiction; it’s a destination that current research is clearly steering toward. Some early-stage clinical work is already exploring how to use stem cells to regenerate pulp and support tooth vitality in humans. It’s cautious, tightly regulated, and limited in scope—but it’s proof that the path from Petri dish to patient is, slowly, being walked.

From Lab Bench to Bedside: The Challenges

Of course, the road ahead is not smooth. Turning a newly identified adult stem cell into a safe, reliable therapy requires answering hard questions.

How do you make sure the cells don’t overgrow or behave unpredictably once reintroduced into the body? Which signals guarantee that the cells become exactly what you want—bone here, dentin there, blood vessels where they’re needed? How do you scale up the process so it’s not just available in cutting-edge university hospitals but in ordinary clinics, for ordinary patients?

➡️ Across Australia scientists are mapping a silent rise in urban heat islands

➡️ Why Australian sleep researchers are rethinking blue light guidance for modern households

➡️ Inside the Kimberley where ancient rock art is reshaping Australian heritage protection debates

➡️ Australia’s coastal planners are revising sea wall strategies as storm surges intensify

➡️ What Australia’s bushfire science reveals about the future of smoke exposure in cities

➡️ How Australian marine biologists are tracking coral recovery after repeated bleaching events

➡️ The quiet shift in Australian coffee culture as climate pressures reshape bean supply

There are technical hurdles too: designing biomaterials that support the cells, crafting scaffolds that mimic the subtle architecture of bone or tooth, finding ways to track and measure success over time. And then there’s the human dimension—regulators, insurers, practitioners, and patients all learning to trust a therapy that doesn’t involve the familiar drill-and-fill approach but something more organic and slow: guided healing from within.

Why This Discovery Feels So Human

Part of the fascination with these adult dental stem cells lies in what they say about our bodies. For most of our lives, we move through the world assuming that what’s lost is lost. A chipped tooth stays chipped. A missing molar is replaced by ceramic or titanium, not by living tissue. Bones heal, yes, but not always perfectly, and large defects can leave permanent traces.

To learn that, tucked away inside our own teeth, there exists a population of cells with the power to rewrite that story is strangely moving. It suggests that we are more resilient than we knew, that evolution has given us hidden tools we’re only now learning to wield deliberately.

There’s also something deeply intimate about the source. These aren’t anonymous laboratory cells or banked donor tissues. They are ours—grown in our mouths, shaped by our daily lives, our nutrition, our genetics. When used therapeutically, they carry a personal continuity: your bone repaired by your cells; your tooth rescued by its own inner workforce.

What This Could Mean for Everyday Lives

It’s easy to file medical breakthroughs under “fascinating but distant.” Yet this particular discovery feels close to home—literally. It may change how parents think about their children’s baby teeth or wisdom teeth, whether they choose to store dental tissue for potential future use. It could reshape dentistry into a more regenerative, less extractive practice, one that emphasizes preserving living teeth over replacing them with inert materials.

For those facing facial injuries, complex fractures, or conditions that weaken the jawbone, the rise of dental-derived stem cell therapies could mean fewer invasive surgeries, faster healing, and outcomes that look and feel more natural. It’s not simply about cosmetics, but about chewing, speaking, smiling—about the many small ways our teeth and bones quietly support who we are in the world.

No one can promise that within a decade you’ll walk into a clinic and grow a brand-new set of adult teeth. Biology rarely moves that fast or that neatly. But the direction is clear: we’re moving from patching and replacing toward repairing and regenerating. And that shift began, in part, with the moment someone looked at an extracted tooth and saw not waste, but possibility.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are these dental stem cell treatments available to the public now?

Most therapies using dental-derived adult stem cells are still in the research or early clinical trial phase. Some experimental regenerative procedures exist in specialized centers, but they are not yet standard care in routine dental or orthopedic practice.

Can adults really regrow a whole new tooth using these stem cells?

Right now, researchers can regenerate certain components of the tooth—such as dentin-like tissue and pulp-like tissue—rather than a fully formed, perfectly shaped new tooth. Entire tooth regeneration in humans remains a long-term goal, not a current reality.

Is it possible to bank or store my or my child’s dental stem cells?

Some private companies offer dental tissue or stem cell banking services, particularly from baby teeth or wisdom teeth. However, the long-term benefits and clinical uses are still being studied, so it’s important to approach such services with informed caution.

Could these stem cells help with bone problems outside the jaw, like leg or hip fractures?

In laboratory and animal studies, dental-derived stem cells have shown strong potential for forming bone. Researchers are exploring whether they can help repair bones in other parts of the body, but widespread use for non-facial bones is still in the investigative stage.

Are there safety risks associated with using adult dental stem cells?

Because these are adult stem cells taken from your own body, the risk of immune rejection is lower than with donor cells. However, as with any cell-based therapy, there are concerns about controlling cell behavior, ensuring they don’t form unwanted tissue, and preventing complications. That’s why rigorous trials and regulatory oversight are essential before such treatments become common.