The first sign that something was wrong was not the numbers on a graph, but the sound of the sea. That’s how one of the researchers later described it. Out on a steel-decked vessel in the screaming winds of the Southern Ocean, she stood at the rail in the half-light of the austral dawn and felt the ship move in a way it shouldn’t. The swell was coming from the “wrong” direction, the waves twisting under the hull like a great animal turning in its sleep. Somewhere beneath the frayed gray surface, a river of water the size of a continent was shifting course.

When the Ocean Turned Back on Itself

The Southern Ocean is not a place that most people ever see. It’s the lonely belt of water that wraps around Antarctica like a stormy halo, a restless moat between the frozen continent and the rest of our blue planet. Down there, the wind is fiercer, the waves taller, the cold deeper. And moving through that chaos is one of Earth’s most powerful physical forces: the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, a vast, unbroken conveyor belt of water that races eastward around the globe.

This current has flowed in the same direction for longer than our species has existed. It’s one of the great constants of the planet, a steady hand turning the gears of the global climate. But over the past few seasons, on a series of quiet readouts from deep-ocean instruments, something deeply unsettling appeared: a major branch of this current, in a key chokepoint of the Southern Ocean, temporarily reversed direction.

It did not last long. It did not need to. For the scientists who had devoted their careers to understanding this wild ring of water, that brief flip was like hearing a mountain crack in winter—just a sound, for now, but the kind that makes you look up and wonder how much snow is about to come down.

The Invisible River That Shapes Our Weather

To understand why this matters, you have to imagine the Southern Ocean not as an empty, hostile frontier, but as a living, breathing engine room. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is its main turbine. Driven by relentless westerly winds, the ACC is the only current that circles the globe without hitting land. In places, it is nearly 2,000 kilometers wide and more than 3 kilometers deep. It moves more water than any other current on Earth.

But this river of water does more than just flow. It stirs. It pulls cold, dense water from the deep and brings it toward the surface. It helps draw down carbon from the atmosphere. It shuttles heat between ocean basins, smoothing out some of the temperature extremes that would otherwise scorch or freeze large parts of the planet. In simple terms: if Earth had a circulatory system, the Southern Ocean would be its fiercely beating heart.

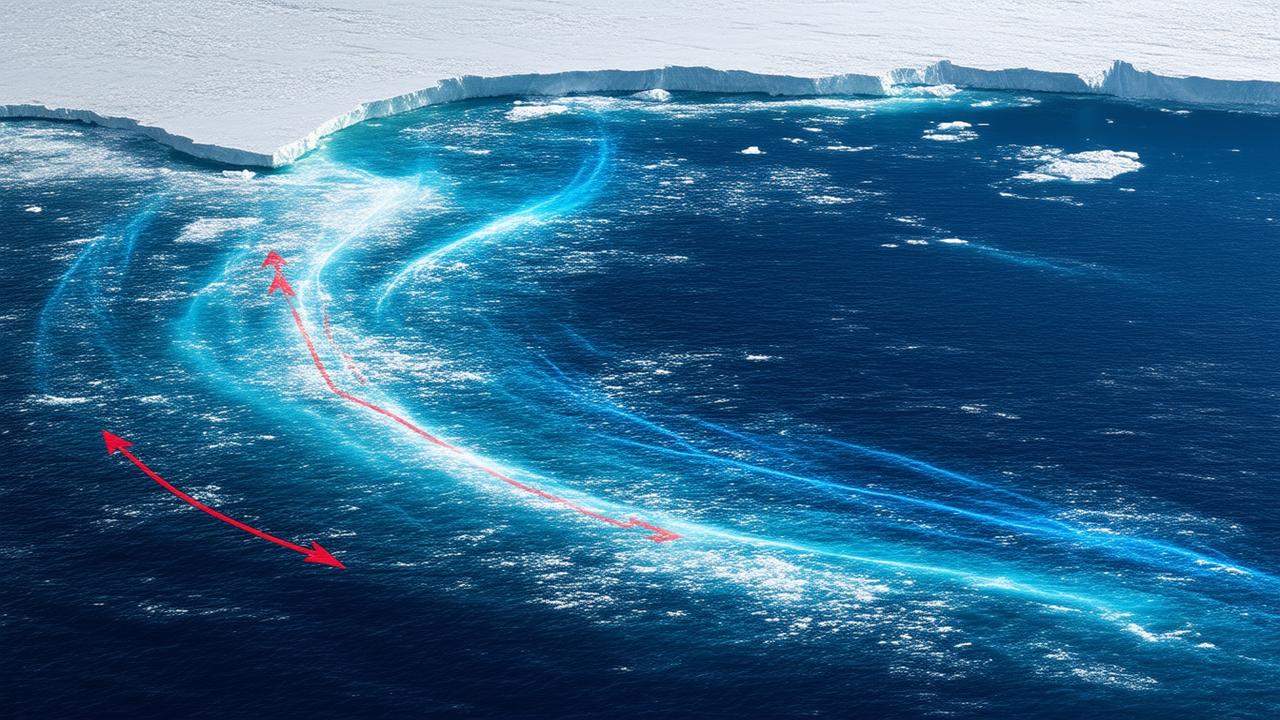

The new measurements showing a reversal weren’t taken from a single instrument; they came from an underwater network. Anchored to the seafloor, strings of sensors listened to the ocean’s motion, recording speed, direction, temperature, and salinity. For years they told a familiar story: a relentless eastward push, punctuated only by the usual turbulence. Then, suddenly, that story shifted. In one critical region—where the current is squeezed between rugged underwater ridges and ice-chilled fronts—the flow paused and then began to move backward.

On paper, it was a line on a chart tilting the wrong way. Out at sea, it was a subtle but profound betrayal of what the Southern Ocean was “supposed” to do.

The Southern Ocean’s Quiet Alarm Bell

To those of us on land, the Southern Ocean’s moods are distant. We feel them only in the background, in storm tracks that curve a little further north, in summers that stretch too long, or in winters that arrive late and half-hearted. But for climate scientists, that brief reversal is the ocean’s version of an alarm clock going off in another room.

The reason is simple: direction matters. Ocean currents are not just moving water; they are moving energy and memory—of heat, of cold, of carbon, of salt. When a major flow changes direction, even for a short time, it hints that the forces driving it have shifted scale. Wind, temperature differences between water masses, the salinity gradients that help water sink or rise—these are the threads that hold the climate system together. Tug them in the wrong way, and the pattern starts to warp.

For decades, models have predicted that as greenhouse gases heat the planet, the Southern Ocean would absorb much of that excess warmth and carbon. It has, heroically so. But nothing can swallow the planet’s fever forever. Warming surface waters become more stratified, like the distinct layers in a cocktail glass: a warm, fresh layer on top, colder and saltier water below. When that layering becomes stronger, it resists mixing—just as oil resists blending with water. The engine that brings deep, cold water to the surface and carries surface water downward begins to stall.

The recent reversal appears to be tied to that stalling, combined with changes in the ferocity and position of the westerly winds. Instead of pushing the current the way they always have, for a time they seemed to shove it sideways, letting it wobble and curl back on itself. The change did not overturn the whole ACC, but it showed that one of its fundamental gears can slip.

| Process | Normal Role in Climate | Risk When Current Behavior Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Antarctic Circumpolar Current Flow | Distributes heat and connects major ocean basins. | Regional climate patterns become more extreme and unpredictable. |

| Deep-Water Upwelling | Brings nutrient-rich, carbon-storing deep waters to the surface. | Reduced carbon uptake by oceans, faster rise in atmospheric CO₂. |

| Surface–Deep Mixing | Balances ocean heat content and delays surface warming. | More heat trapped near the surface, accelerating ice melt and sea-level rise. |

| Polar Front Position | Keeps Antarctic cold isolated, moderating mid-latitude temperatures. | Shifts storm tracks, altering rainfall and drought patterns. |

| Wind-Driven Circulation | Drives stable eastward flow of the ACC. | Increased turbulence, eddies, and potential flow reversals. |

The Domino Effect Reaches Your Doorstep

It’s tempting to box the Southern Ocean off in our imagination: a remote theater, all icebergs and penguins and scientists in bright red parkas. But the flip of that current doesn’t stay down there. It telegraphs outward through the entire climate system like a message in a bottle tossed into a connected sea.

Think of the ocean and atmosphere as partners in a dance. Change the steps in one partner, and the other must adjust. When the Southern Ocean’s circulation wobbles, it can alter the jet streams—the high-altitude rivers of air that guide storms. That means rain belts can shift. Some regions may find that their reliable winter storms suddenly detour hundreds of miles away. Others may be hit by more intense downpours or longer, grinding droughts.

Sea level, too, feels this change. The ocean is not a flat tub; it’s a constantly adjusting, uneven surface where winds and currents pile water up in some places and pull it away from others. A sustained weakening or redirection of Southern Ocean currents can subtly re-sculpt where water gathers, raising regional sea levels beyond what melting ice alone would suggest. For low-lying coastal communities, those centimeters matter. They can be the difference between a storm surge that just floods a road and one that pushes saltwater into drinking wells.

Then there is the carbon story. The Southern Ocean has long acted as one of Earth’s great carbon vaults, drawing in CO₂ from the atmosphere and storing it in its depths. If the mixing slows and the current’s character changes, some of that carbon may instead remain above, lingering in the air, thickening the invisible blanket that warms the planet. In other words, a tired Southern Ocean doesn’t just respond to climate change; it can quietly accelerate it.

Listening to a Planet Breathe

All of this might sound frighteningly abstract, an ocean-wide reshuffling of forces mostly sensed as lines on charts, arrows on maps, and colors on satellite images. But for the people who work in those bitter winds, it is visceral.

Picture a research ship tucked into the lee of an iceberg, the deck slick with freezing spray. A winch whines as a cable is hauled in from more than a mile below. At its end, a cluster of instruments emerges from the steel-gray water—temperature probes, current meters, salinity sensors. Each one carries months or years of memory in its data. On the bridge, a laptop screen flickers to life, plotting that memory as curves and spikes. Somewhere in those lines is the moment the water turned against its long-held direction.

There is a kind of humility in that scene. We are a species capable of altering the chemistry of the sky, yet we still lean over computers in cramped cabins at the end of the world, trying to understand how the ocean is choosing to answer us.

The reversal does not mean the current has permanently flipped. It does not mean an instant catastrophe is rolling toward us on the next tide. But it is a sign that we are pressing the climate system into territory that has no recent parallel, a place where stable giants like the Southern Ocean can start to wobble in unfamiliar ways.

➡️ Why Australian psychologists are studying loneliness as a measurable public health risk

➡️ The surprising role of Australian wetlands in buffering floods and storing carbon

➡️ How Australia’s migration story is influencing modern identity and everyday language

➡️ Australia’s renewed interest in nuclear submarines is reshaping Indo Pacific strategic planning

➡️ What Australian historians now believe about the early contact period along the northern coast

➡️ How Australian supermarkets are quietly changing portion sizes without changing prices

➡️ Why Australian scientists are watching Antarctic ice shelves with growing urgency

What Comes Next, and What It Asks of Us

So where do we go from here, knowing that a major Southern Ocean current has, for the first time observed, flowed backward in a key region?

For scientists, it means more watching, more listening, more measuring. Networks of instruments need to be expanded. Satellites must keep up their silent patrols over the white-capped ring around Antarctica. Climate models need to be refined with this new behavior in mind, testing what happens if such reversals become more frequent or more prolonged.

For everyone else—for those of us who will never feel the sting of polar spray on our cheeks—it means taking seriously the idea that the climate system is not some distant abstraction. It is a physical thing, with currents and temperatures and winds that follow the laws of physics, not the preferences of politics.

When we burn fossil fuels, clear forests, and heat the atmosphere, we are not just “changing the climate” in some vague way. We are reaching into the heavy, saltwater machinery of the planet and turning the knobs. We are making it more likely that ancient, stabilizing patterns will fray: glaciers that held steady for millennia will retreat; seasons will slide around on the calendar; and yes, currents that always ran one way may hesitate, stall, or, in short bursts, flow the other.

The reversal in the Southern Ocean is not a prophecy carved into ice. It is a data point—an alarming one, but still a chance to listen and respond. The story is not finished. We are writing it now, with every decision about energy, land, and the invisible gases we allow to build above us.

Far south, the winds continue to howl around Antarctica. The current steadies itself and resumes its eastward march, for now. But every so often, in the quiet hum of an oceanographic lab, a researcher will open a fresh file of data and scan the lines for any sign that the ocean is turning back on itself again. It is the sound of a planet breathing under stress—and of a species deciding what to do with that knowledge.

Frequently Asked Questions

Has the entire Southern Ocean current permanently reversed?

No. The reversal observed so far is regional and temporary, affecting a major branch of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current in a critical chokepoint. The main current still flows eastward around Antarctica, but this behavior signals that its stability is under stress.

Why is a brief reversal such a big deal?

Because large-scale currents are usually extremely stable. A change in direction suggests that the balance between winds, temperature, and salinity is shifting in a way that could alter how heat, carbon, and nutrients move around the planet. It’s an early warning that the climate system is entering less predictable territory.

Does this immediately affect weather where I live?

Not instantly, like flipping a switch. But changes in Southern Ocean circulation can, over time, influence jet streams and storm tracks. That can alter rainfall patterns, drought risk, and the frequency of extreme weather events in many parts of the world.

Is this directly caused by climate change?

The reversal is consistent with what scientists expect as greenhouse gases warm the planet: stronger and shifting westerly winds, more stratified oceans, and altered mixing. While no single event can be blamed on climate change alone, this behavior fits the broader pattern of human-driven warming affecting the Southern Ocean.

What can be done about it?

Two things matter most: rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions to limit further warming, and improving monitoring of the Southern Ocean so we can detect and understand changes as they unfold. Choices about energy, transportation, food, and land use all feed into the amount of heat and carbon the ocean is forced to absorb.