The morning I turned sixty, I cracked a brown egg into the pan and watched a double yolk slide out—two golden suns wobbling in a small universe of sizzling butter. Outside, the maple tree in the backyard was just starting to blush into autumn. I stood there in my faded robe, spatula in hand, and wondered—for the first time in a long life of breakfasts—why this egg felt somehow “better” than the white ones in the supermarket fridge. Denser. Richer. More… honest, I thought.

My grandmother always swore by brown eggs. “Real farm eggs,” she’d say, tapping the shell with her knuckle like a fortune-teller knocking on a crystal ball. The white ones, she claimed, were “factory eggs,” pale and suspicious. I never questioned it. I just absorbed the story like we absorb most food lore—from the murmurs of family kitchens and the confident pronouncements of people who stir pots with authority.

But that morning, sixty years old and suddenly, inexplicably curious, I realized something unsettling: I’d never actually learned the difference between white eggs and brown eggs. Not really. Not beyond the vaguely moral feeling that brown was “more natural” and white was somehow “mass-produced.” I had carried that unexamined belief through decades of grocery trips and Sunday brunches. And if I, at sixty, still didn’t know, I suspected I was not alone.

The Grocery Aisle Confession

It began, as many late-life revelations do, in the fluorescent glow of the supermarket. The egg aisle stretched in front of me like a personality test: white, brown, “free-range,” “pasture-raised,” “omega-3,” “organic,” labels blooming like wildflowers over neat rows of identical ovals. A young woman beside me was studying cartons like a jeweler inspecting diamonds. She picked up a brown carton, frowned, set it back, then chose a white one with a sigh that seemed disproportionate to poultry products.

On a strange impulse, I asked her, “Do you know if there’s really a difference between the white and brown ones?” It felt oddly vulnerable, like admitting I’d never learned to whistle.

She laughed. “I was going to ask you that,” she said. “I just buy brown because they seem healthier. Right? I mean… they must be?”

We stood there, two strangers of different generations, both operating on myths. I could feel my grandmother’s ghost arching an eyebrow. That was the moment I decided: it was time to learn, properly, what no one in my life had bothered to explain in clear, simple terms.

The Secret Inside the Shell

Here is the thing almost no one told us at the kitchen table: the color of the eggshell is determined almost entirely by the breed of the hen, not by how “good” or “healthy” the egg is. That’s it. Brown eggs come from certain breeds (like Rhode Island Reds or Plymouth Rocks) that lay brown-shelled eggs. White eggs usually come from breeds like the classic White Leghorn.

It’s as unromantic as saying the difference between a black cat and an orange tabby is, well, the color of their fur. But for some reason, we love to weave morality into color. We assign virtue to brown, shadowy suspicion to white, never pausing to ask a hen what she thinks of our theories.

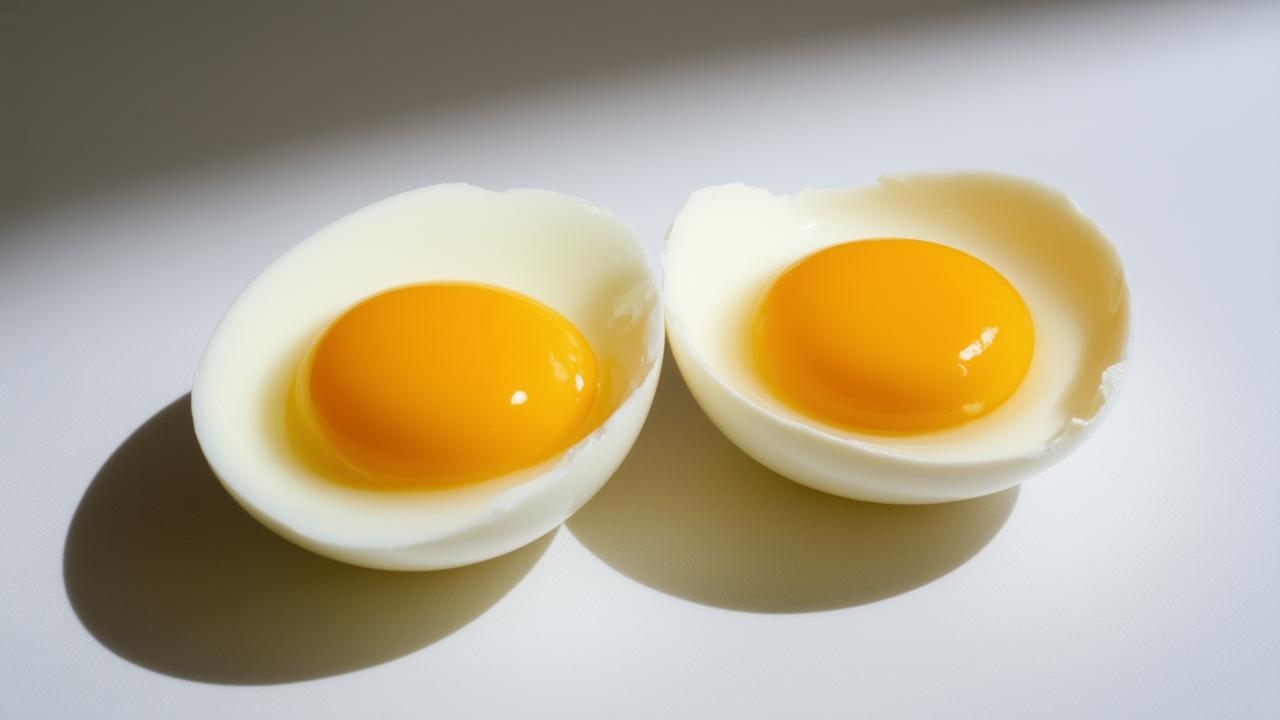

Standing in my kitchen later, with cartons of both colors open on the counter, I waited for some deeper revelation. Were brown eggs heavier? Did they smell different? Did the yolks sit higher, as my grandmother claimed with utter certainty? I cracked one of each into a bowl. Two suns, two runny whites, nearly identical. If I hadn’t seen the shells, I couldn’t have told you which was which.

What Actually Changes — And What Doesn’t

As I started reading and asking questions—farmers at the market, agricultural extension pamphlets, the small-print labels no one ever really reads—I kept circling the same truth: color is not the magic key we think it is. But there are differences in eggs; they’re just not where we’ve been taught to look.

What actually affects the taste, nutrition, and feel of your morning egg is mostly the hen’s diet, living conditions, and health, not the shade of her shell. A hen that spends her days pecking at bugs and weeds, stretching her legs in the sun, eating a varied diet, will often produce eggs with richer, deeper-colored yolks and a more pronounced flavor—regardless of whether the shell is white, brown, blue, or speckled like a tiny universe.

Meanwhile, a hen in a cramped, controlled environment, eating a standard feed and rarely seeing daylight, may produce paler yolks and milder flavor—even if her eggs are proudly brown and sold in an “earthy” carton that looks like recycled poetry.

I like things explained simply, so I sketched myself a little comparison to make sense of it. It ended up looking like this:

| Aspect | White Eggs | Brown Eggs |

|---|---|---|

| Shell Color | From white-feathered, light-eared breeds | From red/darker-feathered, red-eared breeds |

| Nutrition | Similar when hens live and eat similarly | Also similar; color alone doesn’t add nutrients |

| Taste | Varies with diet, not shell color | Also diet-dependent; no inherent “better” flavor |

| Price | Often cheaper in stores | Often pricier due to breed, marketing, and feed costs |

| Perception | Seen as “mass-market” | Seen as “natural” or “farm-fresh” |

That table, plain and unromantic, quietly shattered sixty years of lazy assumptions. I felt almost cheated—and oddly freed.

Why Brown Got a Halo

Once I knew the basic biology, I began to wonder: how did brown eggs earn their halo? Why did so many of us, across generations, develop this quiet conviction that a darker shell meant a better egg?

Part of it is simple history. For a long time, industrial-scale egg production in many countries relied heavily on certain white-egg-laying breeds—efficient layers, good for big operations. White eggs became the default in supermarkets, associated with quantity and standardization. Brown eggs, meanwhile, more often came from smaller farms, mixed flocks, or backyard hens. They were the eggs you got when you knew the person who collected them that morning, still warm from the nest box.

And so our brains did what human brains do: they tied the shell color to the entire story behind the egg. Brown became shorthand for “local,” “small-scale,” “ethical,” and, by a leap of logic nobody really checked, “healthier.”

Then the marketing departments stepped in. Cardboard cartons in friendly browns and greens, words like “farmhouse” and “country,” rustic fonts and little sketched chickens with proud tail feathers. Brown eggs fit right into that story. White eggs, by contrast, looked sterile, industrial, maybe even a little soulless under bright supermarket lights.

The tragedy—and the opportunity—is that the story can be true or false on any given day. I’ve met farmers who sell exquisite white eggs from hens who roam and forage like feathered aristocrats. I’ve also seen neatly branded brown eggs that traveled more miles than I did in my first thirty years, laid by hens who never saw the sun.

The Sound of a Backyard Flock

Once you start untangling egg myths at sixty, you might as well go all the way. That spring, on a breeze that smelled of mud and thawing earth, I brought home three young hens: a speckled Sussex, a stately Rhode Island Red, and a shy White Leghorn. They came in a cardboard box with air holes punched like little constellations.

There is a particular sound a small flock makes on a cool morning—a low, conversational murmur somewhere between purring and gossip. I sat on the back step with a mug of coffee and listened to them explore the yard. The Red scratched confidently under the hydrangeas. The Leghorn moved like a nervous ballerina, all quick steps and darting eyes.

Weeks later, the first egg arrived in the nesting box: a warm, brown oval, still slightly damp, heavier in my palm than I expected. Two days after that, I found a gleaming white egg nestled beside it. In that quiet wooden box, the myths of a lifetime met the reality of three ordinary birds. Same feed. Same backyard. Same day. Different shell. When I cracked them into a pan, the yolks sat proudly high, the whites stayed tight and cloudy, and the kitchen filled with a smell that I can only describe as “real breakfast.”

➡️ France suffers a €3.2 billion blow as a last-minute reversal kills a major Rafale fighter jet deal

➡️ Neither boiled nor raw : the best way to cook broccoli for maximum antioxidant vitamins

➡️ France turns its back on the US and drops €1.1 billion on a European detection “monster” with 550 km reach

➡️ Day will turn to night during the longest total solar eclipse of the century occurring across regions

➡️ No more duvets in 2026? The chic, comfy and practical alternative taking over French homes

➡️ Seniors behind the wheel: will licenses be pulled automatically after 70 from ?

➡️ Goodbye kitchen cabinets: the cheaper new trend that won’t warp, swell, or go mouldy over time

The color of the shell no longer seemed like a moral category. It felt, instead, like a small genetic quirk, like one friend’s freckles and another’s dimples. Charming, but irrelevant to the substance of who they are.

What I Wish I’d Known Sooner

The older I get, the more I value these late-learned truths, not just for what they say about eggs, but for what they reveal about how we move through the world. At sixty, realizing I didn’t know the difference between white and brown eggs wasn’t embarrassing; it was clarifying. It showed me how easily we inherit beliefs and carry them unexamined for decades.

Here’s what I wish someone had leaned over the kitchen table and told me when I was ten, cracking eggs into my grandmother’s mixing bowl:

- The shell color tells you about the hen’s breed, not the egg’s virtue.

- If you care about taste, look for freshness and how the hen lived and ate, not the ink on the carton or the hue of the shell.

- Brown eggs aren’t automatically better; white eggs aren’t automatically worse. You have to look past appearances—just like with people.

- Ask questions about your food. Where it comes from. Who raised it. Curiosity can turn an ordinary breakfast into a story.

I can’t go back and correct the younger version of me, confidently paying more for brown eggs because they “seemed healthier.” But I can stand in the supermarket aisle now with a small, private smile, knowing that the choice between white and brown is a matter of preference, price, and principle—not pigment.

A Little Humility in the Carton

There is an unexpected humility in learning simple things late in life. For me, eggs became a gentle reminder that it’s never too late to ask “why,” even about the most ordinary objects in our hands. The things we think we know—what a “better” egg looks like, how a good life is supposed to appear from the outside—often deserve a second look.

My grandmother, if she were here, might still insist her brown eggs were best. I like to think I’d sit with her at the table, pour the coffee, and say, “You know, it’s not the color. It’s that Mrs. Jensen’s hens were out in the yard all day. They ate better than we did some winters.” And maybe she’d pause, then nod, having learned something at eighty she’d believed differently at twenty.

Now, when I crack an egg—white or brown—into a pan, I notice more. The way the yolk stands or slumps. The scent as it hits the hot butter. The faint chalkiness of the shell under my thumbs. I think of the hen, her day, the invisible thread that runs from a patch of sunlit dirt to my little kitchen. And I think of all the other tiny certainties in my life waiting to be gently examined.

At sixty, it turns out, you can still be a beginner. You can still stand in a grocery aisle, look at a carton of eggs, and say, with more honesty than embarrassment: “You know, I used to think I knew. Now I’m finally learning.”

FAQ: White Eggs vs. Brown Eggs

Are brown eggs healthier than white eggs?

No. When hens are raised and fed similarly, brown and white eggs have nearly identical nutritional profiles. Any differences usually come from diet and living conditions, not shell color.

Why are brown eggs often more expensive?

Brown-egg-laying breeds are sometimes larger and can cost more to raise, and brown eggs are often marketed as more “natural” or “premium.” That perception allows higher pricing, even when the actual egg quality is similar.

Do brown eggs taste better?

Not inherently. Taste is influenced by freshness and what the hen ate, not the shell color. A fresh white egg from a well-fed, outdoor hen can taste far better than an older brown egg from a crowded barn.

Is the shell thickness different between white and brown eggs?

Shell thickness is more about the hen’s age and nutrition than color. Younger hens tend to lay eggs with thicker shells. Both white and brown eggs can be strong or fragile depending on those factors.

How can I choose better-quality eggs?

Look for signs of freshness (check dates, avoid cracked shells), consider how the hens were raised (space, access to outdoors, varied diet), and—if possible—buy from a source where you can ask questions about the flock. Shell color should be low on your list of concerns.