The first sign will not be darkness, but silence. Birds will falter mid‑song. The afternoon air, which only moments before shimmered with heat, will begin to feel oddly hollow, like a room someone has just walked out of. Shadows will sharpen, then stretch and curl in strange, slivered shapes on the ground. People who swore they did not care about the sky will find themselves staring upward, hearts knocking a little faster, as the day slowly forgets it is day. This is how it will begin when the longest solar eclipse of the century turns a bright, ordinary world into something that feels ancient, mysterious, and almost unbearably fragile.

When the Sun Forgets Its Script

Solar eclipses are not rare in the grand scheme of the cosmos, but some of them rise above the rest, lodged forever in the stories people tell. The upcoming one, already scheduled by the clockwork precision of celestial mechanics, will be one of those. Astronomers have run the numbers, traced the geometry of Sun, Moon, and Earth with the clinical calm of orbital equations—and even they admit the result is staggering.

On that day, the Moon will slide perfectly in front of the Sun for a duration so long it almost seems like a mistake in the script of the sky. Totality—those haunting minutes when the Sun’s blazing disk is completely hidden—will stretch toward the theoretical limits of what our planet–Moon arrangement can even allow. Not seconds, not a fleeting glimpse, but a lingering, almost luxurious pause in daylight. The longest of this century.

The path this eclipse carves across Earth will be a narrow ribbon, only a couple of hundred kilometers wide, yet millions will aim for that ribbon. Within it, the Sun will be transformed into a dark hole crowned in pale fire. Outside it, people will witness a partial eclipse—dramatic, yes, but nothing like the full plunge into midday twilight at the centerline. It is in that narrow corridor that the sky will show its most vulnerable face.

The Slow Descent Into a False Night

In the hours leading up to totality, you might not notice anything at all. Life will move along in its usual distracted way: traffic lights change, kettles boil, phones buzz. Yet, if you’re paying attention, you will sense it—the light starting to feel thinner, like it is leaking away molecule by molecule. The sunlit world will be the same, but somehow a bit off, like a familiar room where someone has moved the furniture an inch to the left.

As the Moon begins to nibble at the solar disk, the change will still be subtle. With safe eclipse glasses, you’ll see a black bite taken out of the blazing circle. Without them—if you care for your eyesight—you’ll see little more than an oddly muted afternoon. But as the Moon continues its slow, inevitable crossing, the world’s colors will drain. Saturated greens become washed-out silvers. Faces look pale, as if lit by a strange filter. Insects, confused by the dimming light, may begin their evening chorus hours early.

Then, in the final minutes before totality, the pace accelerates. The temperature falls distinctly; a light breeze may stir where none was before. Shadows turn unnervingly crisp, edges razor‑sharp. On the ground beneath a tree, each leaf hole becomes a tiny projector, casting hundreds of miniature crescent Suns that flicker on sidewalks, car hoods, and outstretched hands. People will murmur, point, fall abruptly silent. Conversation dies in the throat when you sense that something huge, something old as the Earth itself, is about to happen.

The Moment the World Holds Its Breath

The last sliver of Sun will bead along the Moon’s edge like a necklace of light—Baily’s beads—before collapsing into a single, dazzling flash: the so‑called diamond ring. And then, as if someone swung shut a colossal hidden door, daylight will vanish.

Totality.

The sky plunges into an otherworldly twilight. It is not night, not exactly. The Sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona, appears like a ghostly, white halo streaming away into space, delicate and feathery, something you realize you have lived your entire life beneath and yet never seen. Stars ignite across the darkened dome overhead, brighter planets flashing into sudden visibility. On the distant horizon, in every direction, a 360‑degree band of orange and red glows like a permanent sunset, encircling the shadowed world where you stand.

For a solar eclipse this long, that uncanny twilight will linger. Your body will struggle to believe the clock; your mind will insist that something is wrong. Noon does not look like this. People will whisper without meaning to, as if standing in a cathedral. Some will cry, unprepared for how emotional it feels to watch the Sun—our constant, our anchor—momentarily erased. The sky will feel huge and close all at once, like a living presence pressed right up against the planet’s skin.

Why This Eclipse Is So Long

Behind the raw emotion of the experience lies a precise choreography of celestial mechanics. Total solar eclipses happen when the Moon passes directly between Earth and the Sun, casting a narrow shadow onto our planet. But not all total eclipses are created equal. The duration of totality depends on a delicate balance: the distances between all three bodies, the angle of their alignment, and where on Earth the shadow lands.

Sometimes the Moon is a little farther from Earth in its elliptical orbit. It appears slightly smaller in the sky, and even at perfect alignment it cannot cover the Sun entirely, producing an annular “ring of fire” instead of full darkness. Other times, like during this upcoming event, everything lines up near perfectly. The Moon is near its closest point to Earth, looming just big enough to blanket the Sun completely and for a longer stretch of time.

Earth’s curvature and rotation lend a hand too. Near the equator, where our planet spins fastest, the Moon’s shadow has to “chase” the turning surface beneath it, effectively extending the time it takes to cross any one point. When the geometry coincides just right—Moon close, Sun slightly smaller in apparent size, shadow passing near the equator—the duration of totality can push toward the upper limit possible for our era.

In our current cosmic moment, that limit is roughly 7 and a half minutes of total darkness at the very centerline. Most eclipses offer two or three precious minutes. The coming one will nudge close to that upper boundary, making it the longest of the century—a slow, deliberate turning of day into night and back again.

Where the Shadow Will Fall

Though the sky show belongs to everyone, only some will stand in the Moon’s deepest shadow. The Earth’s surface along the path of totality will briefly wear a moving bruise of darkness, racing at supersonic speed but gifting each location along its track with an unusually long dose of totality. Cities and remote fields alike will be transformed into instant observatories. Highways will become rivers of headlights at midday, as travelers angle for clearer skies.

What you see will depend entirely on where you stand. A few kilometers can mean the difference between five minutes of totality and two, between a corona wholly revealed and one truncated by the creeping return of sunlight. Those at the very centerline will have the luxury of time—to gasp, to look around, to notice details many eclipse chasers never manage to see before it is over.

| Experience | Inside Path of Totality | Outside Path (Partial Eclipse) |

|---|---|---|

| Sun’s appearance | Completely covered; corona visible as pale halo | Partially covered; bright crescent Sun |

| Sky brightness | Midday turns to deep twilight for several minutes | Light dimmed but remains clearly daytime |

| Stars and planets | Bright stars and planets become visible | Rarely visible; sky usually too bright |

| Emotional impact | Often described as overwhelming, life‑marking | Striking but more akin to an unusual sunset |

| Eye safety | Eclipse glasses needed except during totality itself | Eclipse glasses needed at all times |

How to Prepare for a Sky That Switches Off

To truly experience this long eclipse, you cannot simply look up from your desk for a few seconds. It calls for intention. For some, that will mean traveling long distances to step into the path of totality. Others will host rooftop gatherings, backyard watch parties, school science mornings that accidentally turn spiritual.

Preparation begins with safety. The Sun is no less powerful because the Moon is in the way. Outside of the brief window of totality, looking at it without proper eye protection can permanently damage your vision. Approved eclipse glasses—those that meet recognized safety standards—let you watch the Moon’s advance safely, turning what would be a deadly glare into a gentle, orange-red disk.

➡️ Marine biologists warn of a troubling shift in orca interactions with vessels, as new research suggests learned aggression and humans refuse to change course

➡️ Psychology explains why overthinking at night is closely linked to the brain processing unresolved emotions

➡️ The forgotten kitchen liquid that leaves grimy cabinets smooth, clean, and shiny again with surprisingly little effort

➡️ “I’m a hairdresser, and this is the short haircut I recommend most to clients with fine hair after 50”

➡️ Drivers receive welcome news as new licence rules are set to benefit older motorists across the country

➡️ New spacecraft images expose interstellar comet 3I ATLAS with a level of detail scientists never expected

➡️ A retiree wins €71.5 million in the lottery, but loses all his winnings a week later because of an app

Beyond eye safety, there is the quieter preparation of attention. Plan, if you can, to step outside well before the peak. Notice how the light shifts on familiar surfaces: your own hands, the walls of your house, the leaves of a nearby tree. If you are in the path of totality, take a moment when darkness falls to look not only up, but around: at the horizon’s ring of firelight, at the faces near you, at the animals puzzled by a night that lasts only minutes.

For a solar eclipse of this length, you may even want to choose your focus ahead of time. The corona? The changing temperature on your skin? The reaction of a child seeing their first sudden night? There is room, for once, to notice more than one thing.

What the Long Shadow Leaves Behind

When the first shard of Sun reappears, the spell breaks almost rudely. Light comes rushing back, swift and brash; birds restart their scattered conversations; insects retreat into the foliage like someone turned off a soundtrack. People laugh, clap, exhale, suddenly aware of how long they have been holding still. Cars start, cameras lower. Life resumes.

But something will remain, even after full daylight is restored. A long eclipse has a way of shifting the furniture in your mind. For many, it is a first visceral encounter with cosmic scale—a direct, bodily understanding that we live on a moving world, under a star that can be hidden by our small gray Moon. It can rearrange one’s sense of permanence. The Sun, it turns out, is not a fixed given, but part of an immense, ongoing dynamic story.

In cultures across history, eclipses have been omens, warnings, messages from gods. Today, we explain them with geometry instead of myth, but their impact on the human heart has not diminished. When day turns to night and back again in the space of minutes, the everyday illusion of control thins. You are reminded, with extraordinary clarity, that you inhabit a universe that does not care whether you are ready for wonder.

Long after this century’s greatest eclipse has passed, stories will remain—of farmers standing in stunned silence by their fields, of commuters stepping out of cars on halted highways, of classrooms emptying as children rushed out under a deepening sky. Phones will hold countless photos, but it is the memory of the air, the hush, the strange light on a loved one’s face that will hold the real power.

Frequently Asked Questions

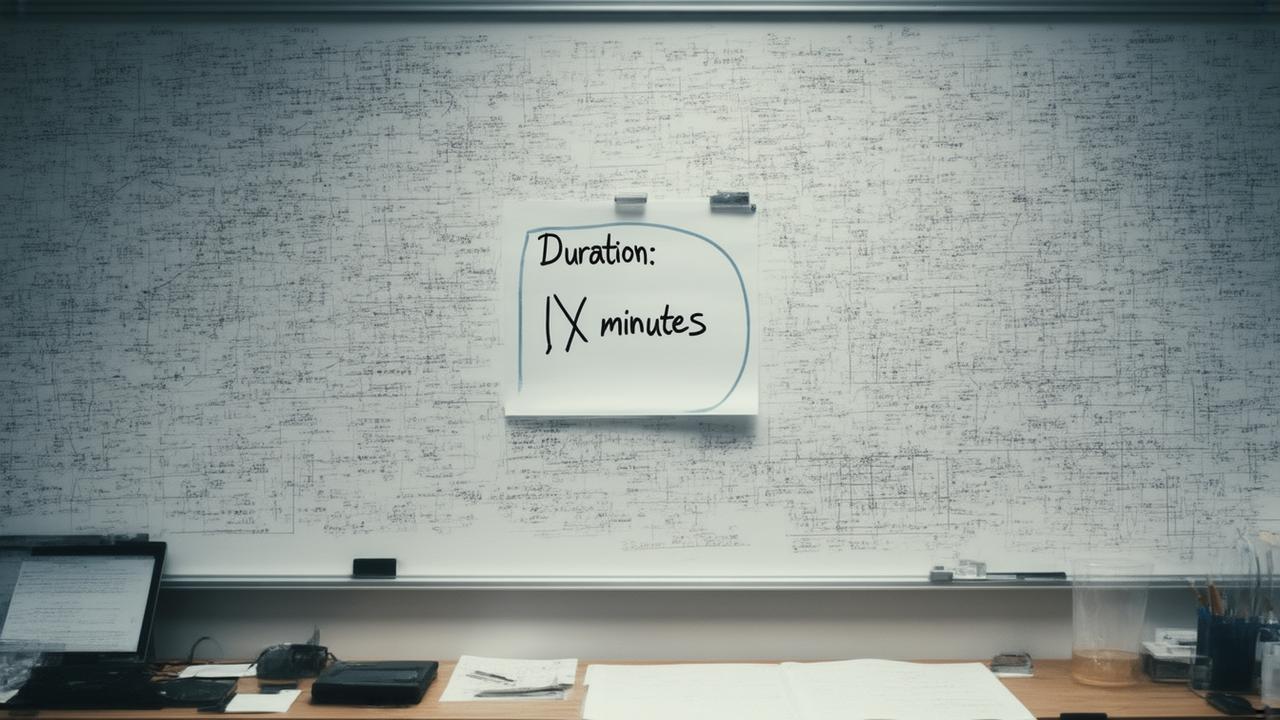

How long will this eclipse actually last?

The entire event, from the first nibble of the Moon to the final return of the full Sun, will take several hours at any given spot. The extraordinary part is the duration of totality at the centerline, which will stretch close to the maximum possible for our era—several long minutes of complete darkness, far longer than most total eclipses.

Is it safe to look at the eclipse?

It is only safe to look at the Sun with the naked eye during the brief period of totality, when the solar disk is completely covered. At all other times—even when the Sun is mostly hidden—you must use proper eclipse glasses or an approved solar viewer. Ordinary sunglasses are not sufficient.

What will animals do during the eclipse?

Many animals respond as if night has fallen. Birds may roost or go silent, diurnal insects quiet down while nocturnal ones stir. Farm animals sometimes head toward barns or exhibit clear confusion. Observing their behavior is one of the most uncanny parts of totality.

Will I notice anything if I am not in the path of totality?

Yes, but it will be more subtle. You will see a partial eclipse if the event is visible from your region: the Sun will appear as a bright crescent through eclipse glasses, and the light may grow dimmer or oddly colored. However, you will not experience full midday twilight, visible stars, or the naked-eye corona.

Why is this called the longest eclipse of the century?

Among all the total solar eclipses of this century, this one offers the longest duration of totality at its centerline, thanks to a nearly ideal alignment of Earth, Moon, and Sun. That rare geometric perfection makes the Moon’s shadow linger over one area longer than in other eclipses, stretching totality toward the physical limit allowed for our current Earth–Moon configuration.