The first thing you notice is the quiet. Not the absence of sound, exactly, but the way familiar noises seem to hesitate. A dog’s bark trails off mid-echo. Someone a few houses down stops mowing the lawn. Even the traffic on the highway sounds strangely muffled, as if the world has taken a breath and forgotten to let it go. Overhead, the sun still shines, yet the light is off by just a shade—too soft, too amber, the way it sometimes looks in old photographs. You squint, not from brightness, but from the unsettling feeling that something vast and invisible has begun to move.

The Slow Dimming of Day

You knew this was coming. The date has been circled on your calendar for months: the longest total solar eclipse of the century, a ribbon of shadow crossing continents and oceans, brushing cities and small towns, deserts and fishing villages. You’ve read the predictions, checked the maps, researched the best viewing spots. Yet none of that fully prepares you for this moment when daylight, of all things, begins to feel negotiable.

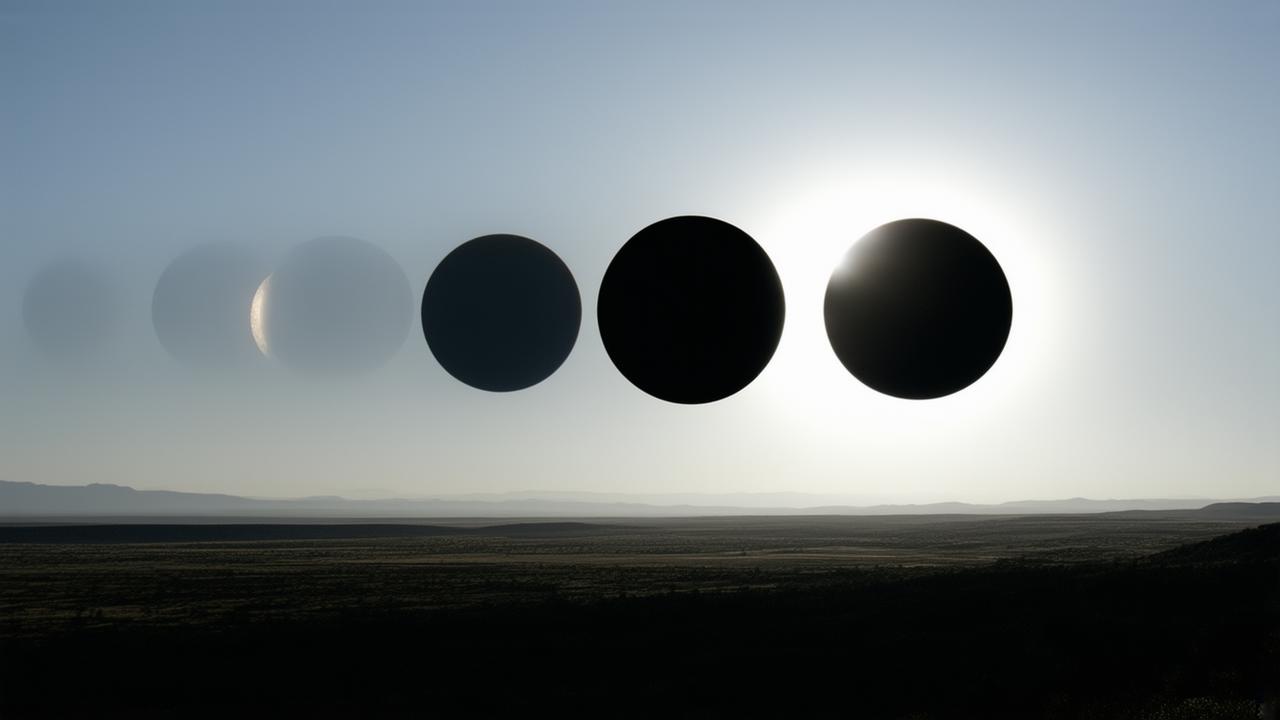

High in the sky, the moon is drifting across the face of the sun, a cosmic coincidence of geometry and distance. From where you stand, the change is gradual, almost polite at first. The sunlight cools to a paler gold. Shadows sharpen, their edges narrowing into razor-thin outlines. An odd clarity settles over the world, as though someone has twisted the focus knob of reality a half-turn too far.

A breeze moves through the trees, but it isn’t like the ordinary afternoon wind. This one feels curious, exploratory, slipping over your arms with a chill that doesn’t match the time of day. The temperature is dropping—only a few degrees, but enough to raise goosebumps. All around you, people are looking up, hands shielding their eyes or clutching eclipse glasses, murmuring to one another in hushed tones. The sky is still bright, but there is a question in it now.

The Path of a Moving Shadow

Across the globe, millions of eyes are turned to the same slow dance. In small rural communities, children cluster outside schools, their teachers explaining orbital mechanics with chalky diagrams and crumpled paper spheres. In bustling cities, office workers crowd onto rooftops and balconies, their usual routines dissolved by the promise of shared wonder. Pilots tilt aircraft windows to give passengers a better view of the darkening arc. On a remote coast, a group of friends wrapped in blankets listen to the surf while the sky, impossibly, begins to dim before dinner.

The eclipse’s path of totality stretches in a sweeping curve, its umbral shadow racing across the Earth at thousands of kilometers per hour. Yet to you, its arrival feels slow, almost reluctant. Minute by minute, the sun becomes a tight, radiant crescent. The light has turned metallic now, sharp and cold, as if the world has been lit by a single, enormous streetlamp hung too high overhead.

Plants react in subtle ways. A few flowers begin to close as if tricked by the false twilight. Birds call uncertainly, their everyday chorus breaking apart into scattered, questioning notes. Somewhere in the distance, a rooster crows at the wrong time, confused by the shifting cues of day and night. Even for creatures who cannot mark dates on a calendar, something about this moment is unmistakably strange.

| Region | Eclipse Experience | Approximate Duration of Totality |

|---|---|---|

| Coastal Towns | Darkened horizon over the sea, reflection of the shrinking sun across the waves | 4–6 minutes |

| Mountain Regions | Shadow racing up valleys and ridges, cool winds spilling down slopes | 5–7 minutes |

| Urban Centers | City lights flickering on, skyline in unexpected twilight | 3–5 minutes |

| Rural Plains | Panoramic 360° sunset effect, clear view of the darkened sun | 6–7 minutes |

When the Last Sliver Disappears

By now, your heartbeat has synced itself to the pace of the changing light. Each fraction of the sun that vanishes feels like a page turning toward an unknown ending. The crescent tightens, thinning to a glowing thread, then to a delicate hook, and finally—almost imperceptibly—to nothing.

Totality arrives with a shock of darkness, fast and absolute. One moment, it is late afternoon; the next, it is night.

The transformation is so complete that your body doesn’t quite know how to respond. Streetlights blink on in confusion. Porch lamps flicker, sensing an evening that has arrived several hours ahead of schedule. You can see the stars—faint at first, then bolder, pricking the sky like pins. Venus burns bright, a gemstone hanging near the black disk of the moon. The temperature has dropped sharply now, and the breath that leaves your mouth feels visible, even if the air isn’t quite cold enough to show it.

Above everything, where the sun once blazed, there is a hole in the sky. The moon, usually a pale companion, has become a perfect black circle, ringed by a delicate crown of light: the solar corona. It streams outward in ghostly tendrils, fine as smoke, arcing and twisting in patterns shaped by the sun’s magnetic field. You stare up, finally able to look directly at the place where no human eyes can usually linger.

The world around you—your street, your town, your chosen patch of grass or rooftop—has become part of a much larger observatory. People gasp, or fall silent. Some raise cameras, but many simply watch, suddenly unwilling to put even a lens between themselves and this impossible, fragile sight.

The Sound of an Interrupted Day

Listen carefully, and you can hear how living things negotiate this sudden night. Crickets start up their evening chorus, chirping from hidden burrows and underbrush, fooled by the rapid fall of light. Night-blooming flowers, usually patient in their timing, begin to unfurl. A bat darts overhead, testing the air, its tiny body a dark, agile silhouette against the eerie corona-lit sky.

If you’re in the countryside, the horizon is a band of fire encircling you—deep oranges and purples where the sun still shines beyond the reach of the moon’s shadow. It is as if you’re standing in the center of a giant, circular sunset. In a city, the effect is stranger still: skyscrapers and rooftops cut black outlines into the sky, while neon signs flicker more seductively in the midday dusk. Windows glow with the artificial yellow of lamps switched on early, people inside briefly stepping away from screens to peer out at a day that has broken its own rules.

There is science, of course, in all of this. Astronomers are measuring tiny temperature variations, mapping the corona, watching the sudden dimming of solar radiation ripple through the atmosphere. Power grids and communication networks feel the eclipse too, in subtle fluctuations and measurable dips. But for most of the people under this passing shadow, the experience is not about data. It is about awe, about the way your own heartbeat sounds a little louder in your ears, about the smallness and significance of standing here, now, at this intersection of celestial bodies and human lives.

The Longest Minutes of the Century

Totality, for all its intensity, is fleeting in an ordinary eclipse—often just a handful of heartbeats strung together into a brief, luminous absence. But this time, the universe has offered something rarer. The alignment of Earth, moon, and sun has given this eclipse a particularly long grace: several full minutes when the day surrenders entirely.

In those stretched-out seconds, you notice things you might have missed in a briefer darkness. The way your own shadow has vanished completely. The faint rustle of leaves as the cooling air settles into stillness. The collective inhale of everyone around you as they try, instinctively, to fix this in memory.

Somewhere along the path of totality, lovers whisper promises, families exchange glances that say, “Remember this.” Photographers exhale after pressing the shutter, knowing their images will never quite convey the rawness of seeing it with bare eyes. On a lonely road, a driver has pulled over on the shoulder, engine ticking as it cools, leaning against the hood of the car to watch the sky and to feel that, at least once, the universe has announced itself so loudly that even a hurried life had to stop and look up.

And slowly—so slowly you almost resent it—the edge of the sun reappears.

The First Diamond of Returning Light

What comes next has its own beauty. As the moon begins to move on, a sharp bead of sunlight bursts from its edge: the “diamond ring” effect. The corona diminishes, brilliance floods back into the sky, and a collective cheer rises from fields, balconies, and beachfronts around the world. It’s not just the return of the sun that people are applauding. It’s relief, gratitude, the giddy feeling of having witnessed something rare and correct and unimaginably old.

➡️ Saudi Arabia quietly abandons its 100 mile desert megacity dream after burning billions and angry citizens demand to know who will answer for this colossal national embarrassment

➡️ Astronomers announce the official date of the century’s longest solar eclipse, promising an unprecedented day-to-night spectacle for observers

➡️ More and more people are wrapping their door handles in aluminum foil — and the reason behind this odd habit is surprisingly practical

➡️ By diverting entire rivers for over a decade, the Netherlands has quietly reshaped its coastline and reclaimed vast stretches of land from the sea

➡️ Day set to turn into night: the longest solar eclipse of the century is already scheduled : and its duration will be extraordinary

➡️ By dumping tonnes of sand into the ocean for more than a decade, China has managed to create entirely new islands from scratch

➡️ By pouring millions of tons of concrete into shallow waters year after year, China turned disputed reefs into permanent military outposts

Day doesn’t simply snap back; it rebuilds itself, layer by layer. Shadows return, faint at first, then stronger. The stars retreat, one by one. Birds restart their conversations, louder now, as if making up for lost time. That chilly eclipse breeze warms into something more familiar, sliding from your skin as if the air has exhaled. Within half an hour, the world looks almost ordinary again.

But you know better. That sky, that sun, that quiet—they’ll never be entirely ordinary to you again.

Carrying the Shadow Forward

Later, when the eclipse is only a story, the details will soften around the edges. You’ll remember the sudden darkness, yes, but also the way someone beside you squeezed your hand just as the last sliver of sun disappeared. You’ll remember the silence, that strange communal pause in which strangers shared a sky and, briefly, a perspective.

Across the regions that lay under its path, the eclipse will leave behind more than photographs and scientific measurements. It will linger in small conversations: grandparents telling children about the day noon turned to midnight; friends recalling how the neighborhood gathered in a cul-de-sac or on a rooftop, faces tilted upward together. It will become a personal timestamp: “That was the year of the long eclipse,” people will say, and the memory of the sky will unfold again in their minds.

There is a humbling comfort in realizing that this event, so tailored to your single lifetime that it’s called “the longest of the century,” is still utterly normal on the scale of the cosmos. Eclipses have come and gone for billions of years, unseen by anything but ancient oceans and patient stone. Yet the one that brushed over your town, your hilltop, your tiny patch of earth—that one belongs to you.

In the evenings that follow, you might find yourself looking up more often. The ordinary sun, now unmasked, will still feel like a mystery. The moon will wax and wane as it always does, but you’ll see it differently—no longer just a pale ornament, but an active participant in the choreography of light and shadow. And perhaps that is the quiet gift of an eclipse: not only the spectacle of day turning slowly to night, but the way it alters your gaze long after the light has returned.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it safe to look at a total solar eclipse with the naked eye?

It is only safe to look at the sun with the naked eye during the brief period of totality, when the sun is completely covered by the moon. Before and after totality, you must use proper eclipse glasses or indirect viewing methods to protect your eyes.

Why does the sky get dark during a total solar eclipse?

The sky darkens because the moon passes directly between the Earth and the sun, blocking the sun’s bright disk. Without direct sunlight, the sky dims to a twilight or nighttime level, allowing stars and planets to become visible.

Why is this eclipse called the longest of the century?

The duration of totality depends on the precise alignment and distances between the Earth, moon, and sun. During this eclipse, those factors combine in a way that produces unusually long totality, lasting several minutes longer than most eclipses of this era.

Do animals really behave differently during an eclipse?

Yes. Many animals rely on light cues to guide their behavior. Birds may roost or fall silent, nighttime insects can begin chirping, and some mammals shift into their evening routines, all in response to the sudden, temporary darkness.

Will there be another eclipse like this soon?

Total solar eclipses occur somewhere on Earth roughly every 18 months, but eclipses with such a long duration of totality are rare. Another comparably long event may not happen again for many decades, or even within your lifetime.