The morning the news broke, Lena was kneeling beside her raised beds, fingertips deep in damp soil that smelled like everything good she’d ever known. A robin hopped along the edge of the path, eyeing the wriggling earthworms she’d disturbed. The water in her old oak rain barrel, dark and cool, waited quietly beside the shed. It was one of those soft, grey mornings when the world feels like it’s whispering rather than speaking. Her kettle sang inside the kitchen. The radio was murmuring too—background noise—until one sentence cut through like pruning shears: “A 135 fine will apply to gardeners using rainwater without authorization starting February 18.”

The Day the Barrel Became a Crime Scene

Lena froze, hands still muddy, knees pressed into the damp kneeling pad. She listened again, certain she’d misheard. A fine? For rainwater? The announcer’s voice continued, clinical and steady, talking about “unauthorized collection systems,” “regulation updates,” and “improper use of non-potable water.” But the words that echoed in her chest were simple: 135 fine. February 18. Gardeners.

She looked over at the barrel. It looked back in its own way—rust-streaked, dependable, the same one she’d hooked up years ago under the gutter to catch the soft drum of rain from her small roof. In summer, she’d lift the lid and breathe in the coolness rising from inside. On scorching days when tap water came out lukewarm and smelled faintly of chlorine, this barrel had felt like a pact with the sky itself.

Now, suddenly, it was evidence.

Out in her tiny patch of green, the breeze brushed past the rosemary, carrying its sharp, resinous scent. A bee nosed into the open face of a calendula flower, oblivious to any decree from city hall. The world was going on as if nothing had changed—but, of course, it had.

Lena wiped her hands on her jeans and went inside, splattering the kitchen floor with soil. She turned up the radio, leaned against the counter, heart tapping a little faster than usual. “Starting February 18,” the voice repeated, “gardeners found using collected rainwater without proper authorization may face a 135 fine.”

A penalty for watering your beans with rain. It felt absurd. It also felt, somehow, personal.

Rain, Rules, and the Uneasy Sky

If you’re a gardener, you probably know that particular kind of disbelief: the one that happens when a rule built far above your head suddenly lands squarely in your flower beds.

For years, harvesting rainwater has seemed like the most harmless of small rebellions against waste. Gutters channeling water into a barrel. A simple downspout diverter, a lid to keep mosquitoes away, maybe a little tap at the bottom that squeaks when you turn it. You hear the rain begin, and you know that somewhere, just a few feet from your tomatoes, your barrel is filling. The planet feels a fraction more forgiving.

Now, the sky’s generosity has been assigned an administrative code.

Officials will tell you there are reasons. And to be fair, there are always reasons. Aging infrastructure that wasn’t built for hundreds of unregulated barrels diverting runoff. Concerns about stagnant water breeding insects or becoming contaminated, then used on crops that might be eaten raw. Complicated water rights that turn every drop into a legal document. In the sterile language of regulations, rain isn’t rain anymore. It’s “graywater,” “non-potable resource,” “catchment volume.”

But that’s not what it feels like when you stand in your yard and look at the clouds. There’s an emotional whiplash to hearing that the water that has always fallen freely on your roses now carries a potential price tag of 135 if you dare collect it without the correct form, stamp, or online account.

A Law That Lands in the Lettuce

The thing about this new rule is that it doesn’t arrive in the abstract. It arrives in the daily rituals of people who know, by feel, how much a plant needs to drink. It shows up at the edge of your raised bed when you reach for the familiar metal handle of your watering can and hesitate, thinking: is this legal water? It makes you second-guess a soft summer shower, wondering if the simple act of placing a bucket beneath your gutter could cost you more than a week’s groceries.

It’s easy to imagine Lena’s neighbors going through their own recalibrations. Across the fence, Mr. Duarte, retired and meticulous, who wakes early to mist his dahlias. The young couple two courtyards over, coaxing balcony herbs from cheap plastic pots. And further out, the community gardens where plots are divided by string and bamboo, where people from half a dozen countries grow the vegetables they remember from back home.

In gardens, the world feels comprehensible: compost in, flowers out. Effort in, harvest out. But regulations like this remind us that even our smallest rituals are woven into larger systems. And sometimes, those systems have very little patience for nuance.

Where 135 Hurts the Most

On paper, 135 may sound like a slap on the wrist. In real life, it’s the difference between paying a bill on time or watching it slide, unpaid, into the next month. It’s the cost of soil for a whole season, or seeds for a neighborhood garden. It’s a week of groceries, a pair of kids’ shoes, a month of transit passes.

In many neighborhoods, rain barrels didn’t appear because of a trend; they appeared because water is expensive. Because summer droughts come with quiet anxiety: Will there be restrictions? Will the municipal taps run slow? Because when you’re stretching every resource, “free water from the sky” is not a poetic phrase—it’s strategy.

To be told that this strategy now requires authorization, that failing to secure that authorization turns your thrifty habit into a punishable offense, is more than an inconvenience. It’s a message about whose resourcefulness is welcome and whose is suspect.

| Use of Rainwater | Before February 18 | From February 18 Onward |

|---|---|---|

| Small backyard barrel without registration | Common, generally overlooked | Potential 135 fine if inspected |

| Registered/authorized rainwater system | Optional in many places | Required for legal use |

| Casual use (bucket under gutter after a storm) | Mostly informal, rarely policed | At risk if reported or inspected |

| Community garden rain tank | Often tolerated, sometimes supported | Must be compliant and documented |

It’s not just the money. It’s the feeling of being watched in a space that once felt like sanctuary. The quiet pleasure of hearing the hollow gurgle as your barrel fills now comes with a new note of apprehension: Is someone keeping track? Could this be the day a clipboard and uniform step through the gate?

The Strange Logic of Punishing Stewardship

What makes this change sting, for many, is the contradiction at its heart. For years, gardeners have been told to be more sustainable. Don’t waste drinking water on lawns. Collect rain. Mulch your soil. Think like a watershed. City campaigns have featured smiling families beside blue barrels, hands on hoses, faces lifted towards an eco-friendly future.

To turn around now and say, “Yes, but only if you’ve filed the correct paperwork, installed the approved system, and stand ready to pay if we catch you doing it wrong,” feels like a bait-and-switch. The very people who responded to calls for stewardship are now first in line for penalties.

Of course, the officials will insist: it’s not about punishing sustainability, but about organizing it. And there is truth there. Unregulated anything can cause problems, and water is not simple. But from the vantage point of a small garden, what you hear is something different: trust, replaced with suspicion.

Listening to the Garden While the Law Speaks

If you step into any garden right now, you won’t hear the new law. You’ll hear the scratch of a trowel, the whisper of leaves in a breeze, the crisp snap of a pea pod. You’ll smell tomato vines when you brush past them—sharp and green and almost impossibly alive. You’ll feel the slight give of the soil under your boots, every footstep a tiny conversation with the earth.

The garden’s language is slow and patient. Laws are not. They appear all at once, dropped like stones into ponds, sending ripples outward. But plants respond to what’s in front of them: the dampness of the soil, the angle of the sun, the quiet generosity or stinginess of the weather. To them, February 18 is the same as February 17: a day to reach for light, to pull water from wherever they can.

Gardeners live between these two tempos—the slow cycle of seasons and the fast pivot of policy. On one side, the intimate knowledge of when the lilacs bloom or the first frost usually comes. On the other, the sudden appearance of a date circled in red not on a calendar, but in the law: February 18, the day your rain barrel crosses a line.

What Choices Do Gardeners Have Now?

Faced with this new reality, options begin to sort themselves like seed packets on a table. Some will quietly remove their barrels, letting the rain rush straight into the storm drains, feeling a little defeated each time it does. Others will move to comply, searching for the right application form, calling understaffed offices, navigating processes that seem designed to make you give up halfway through.

➡️ The simple reason some rooms echo more than others

➡️ The exact reason your phone battery drains faster at night even when you are not using it

➡️ The hidden link between eye contact and trust perception

➡️ Clocks to change earlier in 2026 with new sunset time for UK households

➡️ Yoga experts say breathing patterns matter more than poses for calming the nervous system — here’s why

➡️ The daily drink centenarians swear by: and it’s surprisingly delicious

➡️ Kiwi has been officially recognised by the European Union and the UK as the only fruit proven to significantly improve bowel transit

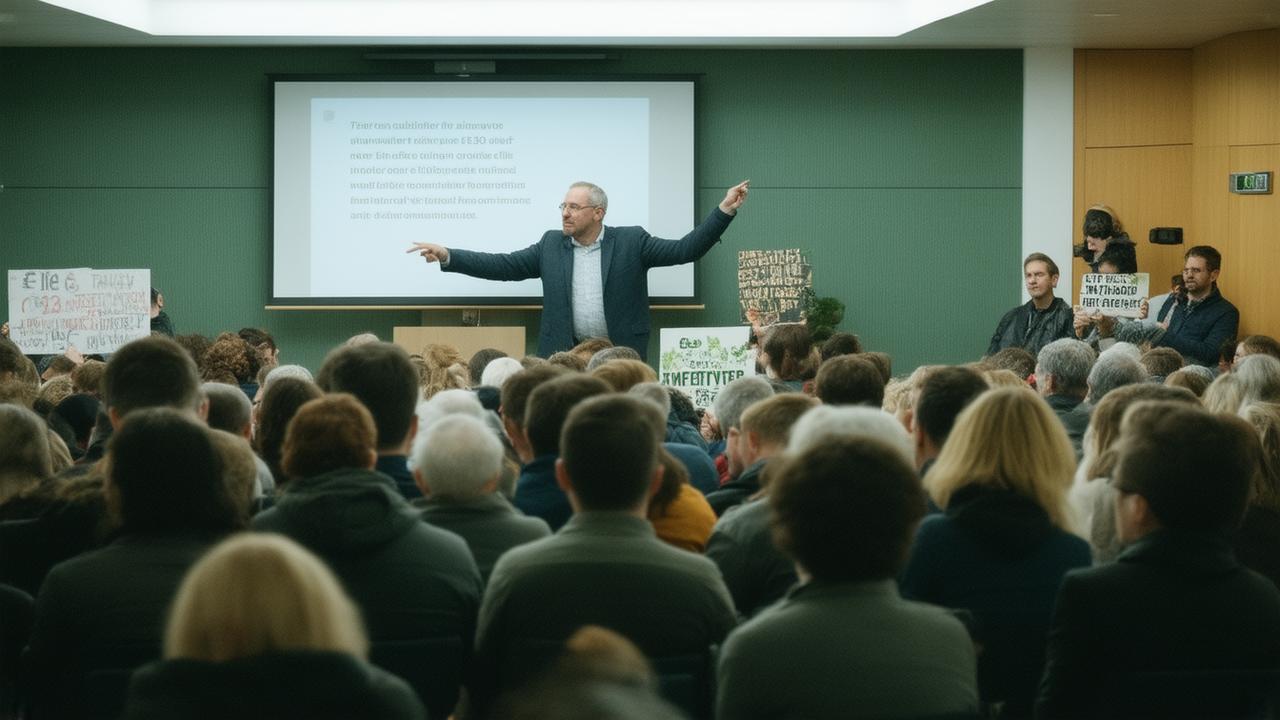

There will also be those who take a different path, who see in this regulation a starting point rather than an end. They’ll organize, compare notes, ask hard questions in public meetings. They’ll point out that punishing small gardeners for using rainwater—while larger, thirstier systems go unexamined—says something uncomfortable about priorities. They’ll argue for clearer, fairer frameworks: for guidelines that distinguish between a backyard barrel and industrial-scale diversion, between neglect and genuine care.

In the meantime, the garden remains what it’s always been: a place where people meet the living world with their hands, not just their opinions. You can almost see it—someone like Lena standing in line at a municipal office, application form clutched in fingers still faintly stained with soil, hoping that the person at the window understands that this isn’t just about a barrel. It’s about a way of relating to the world outside her back door.

Holding on to Wonder in a Regulated Rainstorm

There’s an irony that’s hard to ignore. We live in a time when storms are wilder, droughts longer, weather patterns more erratic. Our relationship to water is already complicated, fraught with urgency and inequity. You might expect that in such a moment, every small act of care—every compost heap, every mulched bed, every thoughtfully placed barrel—would be treated as a precious ally.

Instead, many gardeners now find themselves recast as minor offenders in a story about control. The sky opens; the rain falls; someone, somewhere, writes a rule about how and when you may catch it.

And yet, despite the frustration, the garden keeps offering something that no regulation can fully touch. The first blush of pink on a strawberry. The coolness of the ground under your palms on a hot day. The quiet responsibility that comes from tending soil and knowing the names of the birds that visit your yard. These are forms of citizenship too, though no government office issues certificates for them.

Between Compliance and Defiance

So where does that leave you, standing in your own patch of green with February 18 creeping closer? Perhaps somewhere between compliance and defiance—between the desire to follow rules that (ideally) protect the common good, and the instinctive belief that catching rain from your own roof should not make you a criminal-in-waiting.

You might choose to apply for authorization, to retrofit your system, to keep meticulous notes. You might choose to scale back, to rely more on careful mulching, shade, and drought-tolerant planting. Or you might quietly keep your barrel, eyes open, ready to argue that paying 135 for the “crime” of stewarding water is a sign that something upstream in our priorities has gone awry.

Whatever you choose, remember this: the story isn’t finished. Laws shift. Public pressure works. Conversations grow, sometimes in places as humble as a community garden fence, where someone mentions the new fine and someone else says, “We should do something about that.” These murmured exchanges are how change germinates.

For now, as February 18 approaches, every gardener who has ever smiled at the sound of rain on the roof is living in a new kind of tension. But the sky has not signed any law. It still opens when it will. It still lays its water on shingles and leaves, soil and sidewalks, barrels and bare ground alike. Between those falling drops and the rules written about them, there is still room—for questions, for resistance, for better ideas, and for a more generous imagination about how we share what the clouds give us freely.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is there a 135 fine for using rainwater without authorization?

The fine is being introduced as part of a broader attempt to regulate how rainwater is collected and used. Authorities often cite concerns about water quality, infrastructure planning, and legal water rights. In practice, it means that unregistered or unauthorized rainwater systems are now considered a violation, even if they’re small backyard barrels.

When does the fine start being enforced?

The fine is scheduled to apply starting February 18. From that date forward, gardeners using collected rainwater without proper authorization or registration may be at risk of receiving a 135 penalty if inspected or reported.

Does every rain barrel need to be registered?

Under the new approach, any intentional rainwater collection system—such as fixed barrels, tanks, or cisterns connected to roof gutters—may require authorization. Casual, temporary collection (like placing a loose bucket in the yard) exists in a grey area and may still be subject to penalties depending on how strictly the rule is enforced.

How can gardeners stay compliant with the new rules?

Gardeners who wish to comply should look into whether their local authority offers a registration or authorization process for rainwater systems. This may include filling out forms, following technical guidelines for installation, and using the water only for approved purposes, such as ornamental plants rather than edible crops.

Is it still worth collecting rainwater under these conditions?

Many gardeners feel that rainwater harvesting remains valuable—for plant health, reduced tap water use, and environmental reasons. Whether it is “worth it” now depends on your willingness to navigate the authorization process, your tolerance for risk, and your personal sense of responsibility to both the law and the land you tend.

Who is most affected by the 135 fine?

The impact is felt most strongly by small-scale gardeners and community plots that rely on low-cost, do-it-yourself rainwater systems. For people using rainwater to reduce bills or cope with restrictions, the possibility of a 135 fine adds financial strain and a sense of surveillance in spaces that once felt free and restorative.

Can these rules change in the future?

Yes. Regulations evolve, especially when they generate public debate. If enough gardeners, communities, and local groups speak up—asking for clearer, fairer, and more supportive rules for small-scale rainwater use—authorities may adjust their approach. The story of how we share and care for water is still being written.