The first time I realized I knew almost nothing about eggs, I was standing in the dairy aisle with my reading glasses sliding down my nose, a carton of brown eggs in one hand and white in the other, like some domestic Hamlet. I was 61 years old, the supermarket air-conditioning humming around me, and a flicker of annoyance rose in my chest. Brown eggs were “better,” right? Or was it just something I’d absorbed from decades of casual comments and pretty farm photos? I’d told my grandchildren that brown meant healthier. I’d paid extra for brown more times than I could count. And suddenly, in that over-lit aisle with its glossy tiles and faint smell of spilled milk, I realized: I had no idea what the difference actually was.

The Carton That Called My Bluff

I blame the label. “Farm Fresh Brown Eggs,” it said in looping letters, arranged over a picture of a rosy-cheeked hen strolling through a field of impossible green. No cage, no barn, no fence—just pastoral freedom and a blue sky with the kind of clouds you only ever see in cartoons and insurance commercials.

The white eggs beside them looked plain, almost embarrassed by comparison. No countryside, just a clean logo and a price that was suspiciously lower. They whispered “cheap hotel breakfast” and “factory farm,” even though nothing on that carton had actually said so.

Decades of assumptions pooled in my mind: Brown bread is healthier than white bread. Brown rice is better than white rice. Surely brown eggs had to follow the same path of nutritional virtue. I’d never tested this belief. Never even questioned it. It was one of those little “facts” I’d carried around, passing it on with the quiet confidence of someone who thinks they know how the world works.

Except now, in this moment, I felt something loosen—a tiny, almost imperceptible unhooking of certainty. I put both cartons gently in my cart as if they were fragile ideas, not just breakable shells, and went home to finally learn what I probably should have known at 31, not 61.

The Hen Behind the Shell

The first surprise came from a farmer, not a scientist, though the science backed him up. I was at the local farmers’ market the following Saturday, the air thick with the smells of basil, damp soil, and hot coffee. A man in a faded cap was stacking cartons of eggs, some brown, some white, some a pale, almost mystical blue.

“Which ones are healthier?” I asked, feeling slightly sheepish but also stubbornly determined. “The brown, right?”

He chuckled in a way that was kind, not mocking, like a teacher watching a student finally ask the right question.

“People ask that all the time,” he said. “Color just comes down to the hen’s breed. Brown, white, blue—it’s genetics, same as hair color. Nutritionally, they’re almost identical if the hens are raised the same way.”

He pointed to a speckled hen scratching in a little photo on his sign. “She lays brown. Those white ones over there come from my Leghorn hens. Same pasture, same feed, same sunshine. The shell is just a jacket.”

It felt strangely humbling. Sixty-one years of life, and I’d never thought to ask what kind of bird produced what kind of egg. I’d treated eggs like simple objects, not messages from specific animals with specific bodies and histories. The farmer explained that white-feathered hens with white earlobes often lay white eggs, and red-feathered hens with red earlobes often lay brown eggs. A detail so small and charming that I almost laughed.

At home, curiosity turned into a quiet, nerdy obsession. I read articles, watched a video of a calm-voiced veterinarian explaining shell pigments, and learned that brown coloring comes from a pigment called protoporphyrin IX, deposited on the shell as it forms. Some breeds add it, some don’t. The yolk color—so often the focus of passionate debate—is mostly about what the hen eats. More greens and insects can mean a deeper gold. More corn can bring a lighter hue. But brown versus white shell? That’s just feathered genetics, strutting around the barnyard completely unaware of our human myths.

What We Think We’re Buying

Still, the myth has roots. Brown eggs are often more expensive, and price has a way of masquerading as quality. Standing in another store aisle weeks later, I realized how easy it is to equate cost with goodness, and simplicity with lack. But what I learned is subtler, and more unsettling in its ordinariness: we aren’t paying for color. We’re paying for context.

In many parts of the world, brown-egg-laying hens tend to be larger breeds, sometimes needing more feed. That can make costs a little higher. Brown eggs also became associated with smaller farms and traditional breeds, while large commercial operations often favored the efficient, white-egg-laying Leghorn. Over time, “brown” and “farm” fell into a comfortable, unexamined partnership in the public imagination. Marketing did the rest, sketching pastoral scenes wherever they could squeeze them.

It took me months to fully untangle my own mental shortcuts. This wasn’t just an egg story—it was a story about how quickly we build quiet hierarchies of “better” and “worse” based on surface appearances. I found myself thinking of other assumptions I’d carried: about people’s clothes, accents, neighborhoods; about which foods were “real” and which were “cheap.”

In a notebook I keep on the kitchen counter, I started jotting down little things I thought I “knew” and then fact-checking them. It became a sort of late-life game—testing the scaffolding of my own beliefs. Every time something toppled, I felt oddly lighter.

Nutritional Myths, Cracked Open

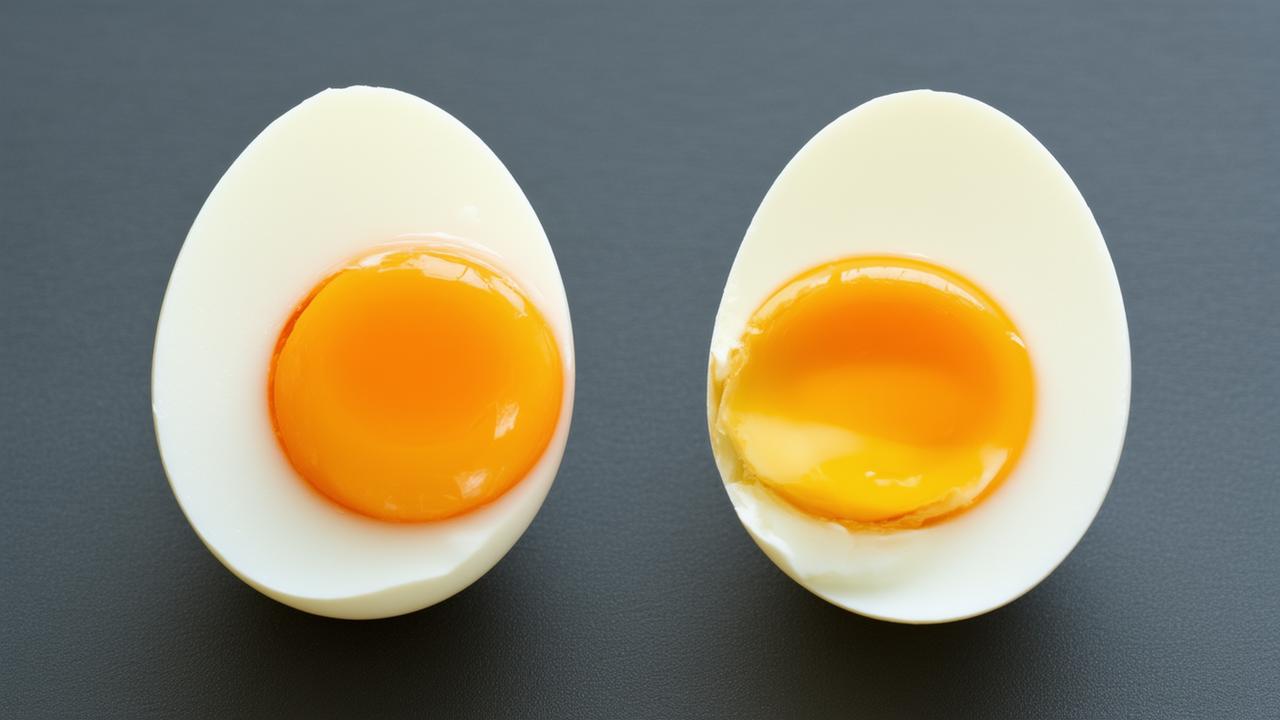

One afternoon, with a pot of water barely trembling on the stove, I decided to stop guessing and start comparing. I set two eggs on the counter—one brown from the farmer’s market, one white from a grocery-store dozen. I cracked them gently into separate bowls and studied them.

Their yolks were nearly the same color. Their whites settled into similar pools of translucent shimmer. Had there been no shells as clues, I’d never have known which was which.

Modern nutrition data confirmed the scene in my kitchen: calories, protein, fat, vitamins—they line up closely across shell colors, provided the hens live similar lives and eat similar diets. The real differences come not from brown versus white, but from:

- What the hens are fed

- How much space they have to move

- Whether they spend time outside

- How stressed or healthy they are

It made sense. A shell is a container, not a moral statement. But we humans love using color as a shortcut for value, a tiny visual cue that lets us feel like we’ve made an informed decision in a brief glance.

| Feature | Brown Eggs | White Eggs |

|---|---|---|

| Shell Color Source | Pigment from certain breeds (often red-feathered hens) | Lack of pigment in specific breeds (often white-feathered hens) |

| Typical Price | Often slightly higher in stores | Frequently lower |

| Nutritional Value | Similar to white when hens have similar diet and living conditions | Similar to brown when hens have similar diet and living conditions |

| Taste Difference | Depends on hen’s diet and freshness, not color | Depends on hen’s diet and freshness, not color |

| Cultural Perception | Often seen as more “natural” or “farm-fresh” | Often seen as “industrial” or “basic” |

Learning to Taste What Actually Matters

When I finally started paying close attention to eggs—not their packaging or their price tag, but their flavor—I noticed something I’d never bothered to see. Fresh eggs, whether brown or white, feel alive in your hands: the whites gather tightly when cracked into a pan, the yolks stand up proudly, domed and bright. Older eggs, no matter the color, spread more, slumping a little in the skillet, weary travelers from some distant warehouse.

The taste shifts, too. An egg from a hen that spent her days wandering through grass and pecking at bugs carries a more complex flavor—richer, sometimes almost grassy, with a silkier yolk. That complexity can come in a brown shell or a white one. My tongue cannot tell the shell’s color. It can only tell me about the life that produced what I’m eating.

There’s something quietly radical in choosing to care about those invisible stories. It’s easier to stand in front of a wall of cartons and rely on shorthand: brown means “good,” white means “less good.” But once the myth falls away, you’re left with more honest questions. How was this hen raised? What did she eat? How far did this egg travel?

➡️ If you want your kids to respect you when they are older stop clinging to these 8 selfish habits

➡️ Goodbye microwave as households switch to a faster cleaner device that transforms cooking habits

➡️ Goodbye to the dining table : the new trend from abroad that replaces it for good in homes

➡️ Most people store cleaning products incorrectly, making them less effective

➡️ Heating: the 19°C rule is outdated: experts reveal the new recommended temperature

➡️ Michael Schumacher, the new separation

➡️ Marine biologists warn of a troubling shift in orca interactions with vessels

At 61, I started bringing those questions into my kitchen like new, slightly demanding guests. I asked store employees if they knew anything about their suppliers. I chatted with farmers about feed and space per bird. Sometimes the answers were vague and unsatisfying. Sometimes they were precise and reassuring. Either way, I felt more awake in my own life, as if a small part of my daily routine had shifted from autopilot to intention.

The Humbling Gift of Being Wrong

The older I get, the more valuable it feels to be wrong in public—about eggs, about anything. There’s a certain stubbornness that can harden with age, like cooling caramel. We get attached to the stories we’ve told for years, even the small ones about breakfast food.

Discovering how little I knew about something as ordinary as egg color didn’t make me feel foolish for long. Instead, it softened me. If I could be so sure about brown eggs being “better” and be so thoroughly mistaken, where else might I be carrying little untested certainties?

It changed how I talk to my grandchildren. Before, I might have pronounced: “Brown eggs are healthier, so we buy those.” Now, I crack eggs with them at the counter and say, “Isn’t it interesting that they look different on the outside but are almost the same inside? Let’s think about what really matters here.”

They ask questions with wild, wandering curiosity: Could a hen lay a rainbow egg? Do blue eggs taste like blueberries? Why don’t we eat ostrich eggs every day? The kitchen becomes a laboratory of wonder, and I try hard not to rush their questions toward neat, simplified answers. I want them to carry fewer quiet myths than I did, or at least to hold those myths more lightly, ready to set them down when new information arrives.

What I Choose Now, and Why

These days, when I reach into the egg case, I look less at color and more at clues: words like “pasture-raised” or “small farm,” or a label from a producer I’ve actually spoken to. I don’t avoid white eggs at all; instead, I welcome the chance to ask where they came from. Brown no longer feels virtuous. White no longer feels inferior. They are simply variations of the same quiet miracle: a self-contained universe of nourishment in a thin, fragile shell.

Standing there in the cool hum of the refrigerated aisle, I think of that first moment of realization at 61, and I feel oddly grateful. All it took was a carton of eggs to remind me that learning isn’t something we leave behind in our twenties, or our forties, or at retirement. It’s something that can slip into the most mundane corners of our lives—into breakfast, into grocery lists, into the color of a shell we’ve cracked a thousand times without once really seeing.

I used to believe that wisdom meant arriving at a set of solid truths. Now I suspect it has more to do with being willing to gently question even the smallest, most ordinary beliefs. To hold up a brown egg and a white egg side by side and say, quietly, “I thought I knew. Maybe I don’t. Let’s find out.”

And in that simple, everyday act—over a frying pan, in a market stall, under the neon lights of a supermarket—you discover that the world is still bigger than your assumptions, and that the most ordinary objects can still surprise you. Even, perhaps especially, at 61.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are brown eggs healthier than white eggs?

No. Brown eggs are not inherently healthier than white eggs. Their nutritional value is almost identical when the hens are raised under similar conditions and given similar feed. The main factor affecting nutrition is how the hen lives and what she eats, not the color of the shell.

Why are brown eggs often more expensive?

Brown eggs can cost more for a few reasons. In some regions, brown-egg-laying breeds are larger and may eat more feed, slightly increasing production costs. Brown eggs have also become associated with small farms and “natural” branding, and sometimes you’re paying more for that image or for better farming practices—not for color itself.

Do brown eggs taste different from white eggs?

Any noticeable difference in taste usually comes from the hen’s diet and the egg’s freshness, not from shell color. A pasture-raised white egg can taste richer than a brown egg from a hen raised indoors on a basic diet, and vice versa.

Is the yolk color related to the shell color?

No. Yolk color is mostly influenced by the hen’s diet. Hens that eat more greens, insects, or certain natural pigments produce darker, more golden yolks. Shell color and yolk color are controlled by different factors and don’t depend on each other.

How should I choose eggs if color doesn’t matter?

Focus on how the hens were raised and how fresh the eggs are. Look for information about pasture access, type of feed, and farming practices. If possible, buy from local farmers or producers you trust. Let the story behind the egg guide you more than the color of its shell.