The first time I realized most people don’t actually know the difference between white and brown eggs, I was standing in the grocery aisle on a Tuesday afternoon, holding a carton in each hand like they were rare artifacts. One carton, pristine and clinical, with twelve white eggs lined up like polished stones. The other, brown-shelled and speckled, looked like something you’d collect from a henhouse at dawn, the chill of morning still clinging to them. A young couple next to me debated in low, serious whispers. “The brown ones are healthier,” she said. “No, the white ones are cleaner,” he insisted. They looked so sure. It struck me then—at sixty years old—that I had gone my entire life accepting those same untested assumptions, never really questioning what any of it meant.

An Old Story About Eggs and Assumptions

I grew up in a kitchen that smelled like black coffee, bacon grease, and whatever my mother was baking that day. Sunday mornings meant eggs. Always eggs. My mother swore by white eggs, as though the color itself were a stamp of virtue and reliability. “The brown ones are for bakeries and restaurants,” she’d say, “not for us.” I never asked why. Children rarely question the quiet myths of their households; we absorb them like steam from a boiling pot.

Decades passed. I moved out, started my own rituals, shopped in supermarkets under fluorescent lights instead of the corner market with its sticky linoleum floors. I saw the rise of organic labels, free-range promises, and farmer’s market aesthetics. Brown eggs suddenly became fashionable, dressed in recycled cardboard cartons with earnest typography. It was as if someone had decided that brown automatically meant better, kinder, more “natural.”

And I believed it. I paid the extra dollar or two, feeling like I was doing something vaguely noble and nutritionally wise. I never really checked. I never really asked. I had upgraded my myths, that’s all—traded my mother’s faith in white for a new faith in brown.

The Moment Curiosity Finally Spoke Up

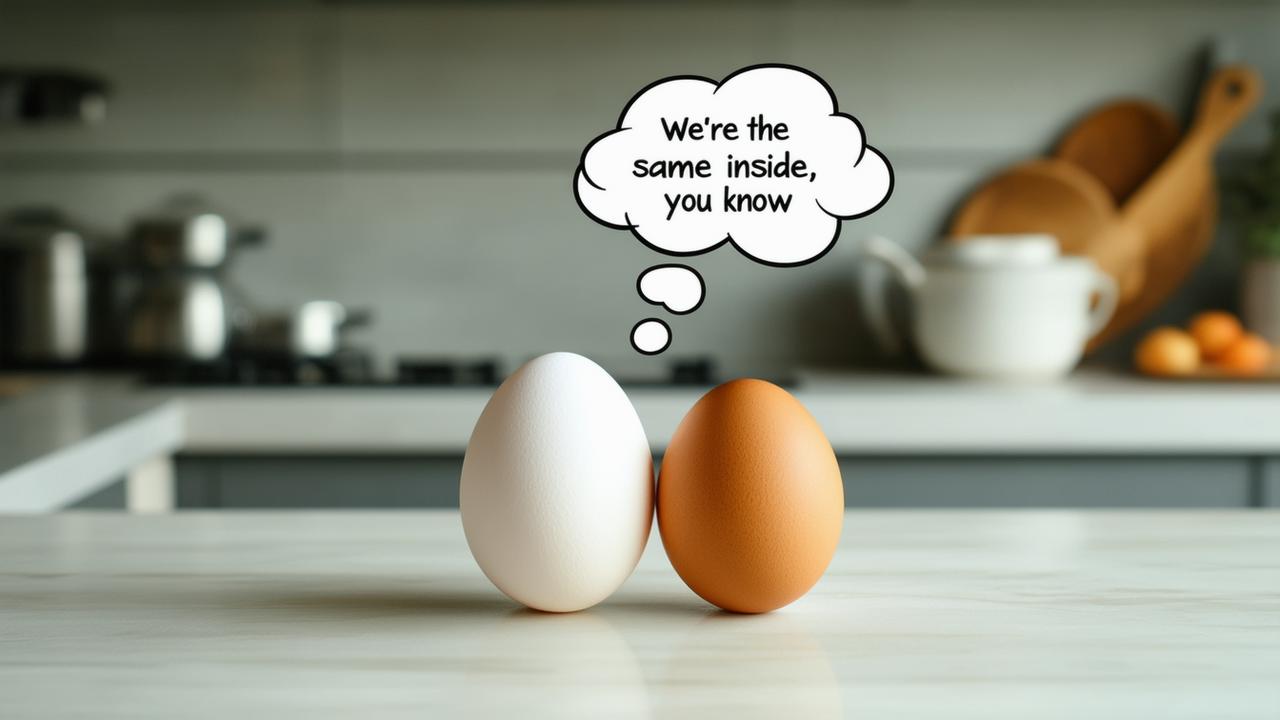

One slow afternoon, years into retirement, I found myself with a curious kind of free time—no deadlines, no school pickups, no office politics to replay in my head. I bought a dozen brown eggs from a local farm stand, brought them home, and set them on the counter next to a carton of supermarket white eggs. They sat there, side by side, like two generations who shared more in common than they realized.

I cracked one of each into separate bowls. The yolks were startlingly similar—sunny, round, familiar. The whites spread out in nearly identical translucent pools. No dramatic color contrast, no richer orange from the brown egg, at least not this time. Just… eggs. I tasted them, salted and scrambled, in the quiet of my kitchen. If there was a difference, it was one my imagination had to work hard to find.

Curiosity, properly awakened at last, doesn’t go back to sleep easily. I started reading. Not the glossy label language or the marketing copy, but agricultural reports, extension office pamphlets, notes from small farmers trying to explain their world to people like me. And there, buried in the plainspoken language of poultry science, was the thing I had somehow missed for sixty years: the color of the shell has almost nothing to do with the healthiness or taste of the egg.

What Color Really Means (and What It Doesn’t)

The difference, it turns out, begins not in the carton, but in the hen. A chicken’s breed largely determines its shell color. White-feathered hens with lighter earlobes tend to lay white eggs. Red-feathered hens with darker earlobes usually lay brown eggs. Some breeds lay blue or green eggs, too, but those rarely make it into the standard supermarket scene.

The egg shell color is a kind of genetic fingerprint, not a nutritional report card. The pigments that tint the shell—protoporphyrin for brown, oocyanin for blue-green—sit on the outside like paint on a house. Underneath, the house is built the same way. The hen’s diet, health, and living conditions can affect the richness of the yolk and the subtlety of flavor, but the shell color itself is just… shell color.

Here’s how some of the most common beliefs stack up against what I eventually learned:

| Common Belief | Reality |

|---|---|

| Brown eggs are more nutritious than white eggs. | Nutritional differences come from the hen’s diet and environment, not shell color. |

| White eggs are factory-farmed; brown eggs are “farm-fresh.” | Both colors can come from either large farms or small backyards. Color doesn’t reveal farming practices. |

| Brown eggs taste richer. | Taste is influenced by the hen’s feed and freshness, not the shell’s shade. |

| Brown eggs are more “natural.” | Shell color is simply genetics. Both white and brown eggs are equally “natural.” |

| White eggs are lower quality. | Quality is about freshness, handling, and the hen’s health, not shell color. |

The more I read, the stranger it seemed that I had spent decades believing in the moral superiority of one shell over another. I had never asked a single chicken what she thought about any of this.

Why Brown Eggs Often Cost More

There is one place where color does matter, though—not in the egg itself, but in your wallet. Brown eggs often cost more, and I used to think that meant they were better for me. In truth, the reason is more practical than poetic.

Many brown-egg-laying breeds are larger birds. Larger birds tend to eat more feed. More feed means higher costs for farmers. Those costs ripple forward, quietly, until they land in the price tag you see on the shelf. Sometimes, brown eggs are also associated with niche markets—small farms, specialty brands, certain regions—where prices are already higher. The egg inside may not be more virtuous, but the supply chain behind it is smaller, and that, too, comes at a cost.

It’s not that brown eggs are a scam. It’s that the story we tell about them is incomplete. We often stop at the shell and never look beyond it. We forget that a hen does not know she is laying something that will end up as a lifestyle statement on someone’s brunch plate. She only knows her daily business of scratching, pecking, surviving, producing.

The Quiet Lessons of a Simple Egg

At sixty, the world looks both familiar and strange. You think you’ve seen it all, until a carton of eggs humbles you. That humility has a sound: the soft crack of a shell against the rim of a bowl, the way the yolk trembles for a moment before it settles into itself. I found myself paying attention in a way I hadn’t in years.

Now when I shop, I no longer let color guide my choices. I read the tiny words instead: “pasture-raised,” “free-range,” “cage-free,” “conventional.” None of these are perfect terms, and they’re often muddled by marketing, but they tell me more than the pigment of a shell ever could. I ask myself different questions: How were these hens kept? What were they fed? How far did these eggs travel before they reached my hand?

Sometimes, I still buy brown eggs from a farmer who sets up at the edge of town, his truck bed lined with old wooden crates. Sometimes I buy white eggs from the grocery store when I’m in a hurry and the budget feels tight. Both crack the same. Both sizzle in a hot pan with that familiar whispering sound, the edges curling just slightly, the whites turning from transparent to opaque like a slow, small magic trick.

➡️ It’s official and it’s good news: from February 12, gas stations must display this new mandatory information at the pump

➡️ Many people don’t realize it, but cauliflower, broccoli and cabbage are all different varieties of the very same plant

➡️ Marine authorities issue warnings as orca groups increasingly, according to reports, show aggressive behaviour toward passing vessels

➡️ It’s official, and it’s good news: from February 12, gas stations will have to display this new mandatory information at the pump

➡️ Major breakthroughs in diabetes care are marking a medical turning point that could soon make many of today’s treatments obsolete

➡️ I only learned this at 60: the surprising truth about the difference between white and brown eggs that most people never hear about

➡️ Moist and tender: the yogurt cake recipe, reinvented by a famous French chef

There’s a quiet joy in realizing you’re allowed to change your mind at any age, even about something as unglamorous as an egg. It means your curiosity is still alive. It means you haven’t fully hardened into your shell just yet.

What I Tell People Now

When friends ask—which they do, now that they know I’ve gone down this strange little rabbit hole of poultry knowledge—I tell them this: Don’t argue about white versus brown. Argue about how the bird lived. Ask about the farm, not just the carton. If health is your concern, focus on freshness, storage, and overall diet, not the shade of your breakfast.

I also tell them to taste with their eyes closed once in a while. Crack a white egg and a brown egg, cook them simply, and see what you notice. Not what you expect to notice, not what you’ve been told to notice, but what your senses quietly report back. Let your tongue and your nose and your memory be the judges, not the marketing claims, not the price tag.

Because beneath it all, the egg has always been a modest thing: a promise wrapped in calcium, a beginning that usually ends in a frying pan instead of a nest. It deserves, at the very least, that we see it clearly.

I learned at sixty that the difference between white and brown eggs is mostly a story we tell ourselves—a story layered with habit, nostalgia, marketing, and half-truths. The real difference lies elsewhere: in land and feed, in barns and sunlit yards, in the quiet lives of animals we rarely see. Once you know that, it becomes impossible to look at a carton—any carton—the same way again.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are brown eggs healthier than white eggs?

No. The nutritional content of an egg depends on the hen’s diet and living conditions, not the color of the shell. A brown egg and a white egg from hens raised the same way will be nearly identical nutritionally.

Why do brown eggs cost more?

Many brown-egg-laying hens are larger breeds that eat more feed, which raises production costs. Brown eggs are also often sold by smaller farms or specialty brands, which can add to the price. The higher cost doesn’t automatically mean they’re more nutritious.

Do brown eggs taste better than white eggs?

Taste differences usually come from the hen’s diet and the egg’s freshness, not shell color. Farm-fresh eggs may taste richer than older supermarket eggs, whether they are white or brown.

Is the shell of a brown egg thicker than a white egg?

Shell thickness is influenced by the hen’s age and nutrition, not shell color. Younger hens often lay eggs with thicker shells, whether white or brown.

What should I look for when choosing eggs?

Look beyond color. Consider freshness (check the date), how the hens were raised (such as pasture-raised or free-range, where available and verified), and how the eggs have been stored and handled. These factors matter far more than whether the shell is white or brown.