The skull sat under the soft beam of the lab lamp, its bone surface the color of weathered shells. Outside, the afternoon buzz of the city hummed through double-glazed windows, but in here time felt strangely folded. A digital caliper clicked softly against bone, a pencil sketched faint lines on transparent acetate, and a computer screen glowed with a ghostly, half-formed face. Two centuries after this person had breathed, sweated, and strained under the iron discipline of the convict system, they were, in some quiet, careful way, returning.

The Silent Return of the Transported Dead

For decades, the story of the convict era was told mostly in words: lists of names, grainy ink on yellowed shipping records, faded court transcripts that smelled faintly of dust and the oil of old leather bindings. Historians reconstructed lives from marks on paper—a theft here, a sentence there, the journey across the world compressed into a single declarative line: “Transported for seven years.”

Those stories mattered. They still do. But they were, by their nature, strangely bodiless. The convicts became data points, not people. They existed as causes and effects—poverty, crime, punishment, labor, death—yet their faces were lost, their gestures gone, their particular human presence dissolved into statistics and stereotypes. The “convict” became a category, not a person you might pass on the street, not someone whose eyes you might meet.

Now, in climate-controlled labs and bright, humming studios, that absence is being challenged. Forensic reconstruction—once the domain of crime investigation and modern missing persons cases—has stepped quietly across the threshold of history and taken a seat beside the archivists and archaeologists. The result is something almost unsettling: the past is acquiring faces again.

Bone, Software, and Imagination Working in Tandem

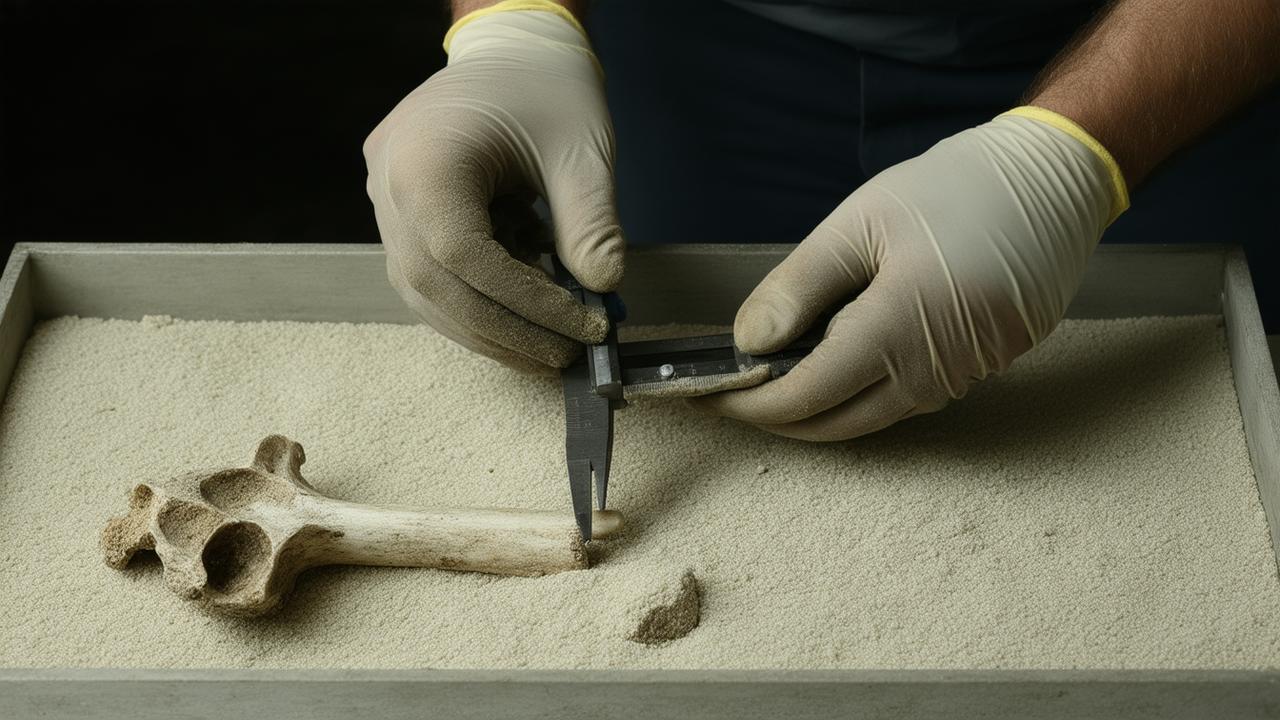

Walk into one of these labs and it feels like standing at the edge of two worlds. On one bench lie fragments of human remains excavated from long-closed burial grounds associated with old penal colonies or work camps. On another table, high-resolution scanners hum and rotate, translating bone into data—microscopic ridges and contours mapped with almost reverent precision.

From there, the work moves into the digital ether. A skull becomes a 3D model: rotatable, measurable, annotatable. Tissue-depth markers are placed based on databases built from contemporary population studies. Layer by virtual layer, muscle structure is approximated, skin thickness estimated, the angle of the jaw considered not just as geometry but as a hint of expression.

This process is not just technical; it is deeply interpretive. Forensic artists and anthropologists sit side by side, debating subtle slopes and gentle curvatures. They review what is known: age at death, sex, signs of malnutrition or hard labor, evidence of healed fractures or chronic disease. They listen to the bones the way a historian listens to a diary.

Yet the act of reconstruction is never purely mechanical. It hangs between craft and science, guided by established protocols but colored by a careful kind of imagination. This tension—between accuracy and empathy, between data and human feeling—defines the new phase of convict-era research.

The New Face of an Old Record

Imagine looking at an old transportation list—rows of names, crimes, sentences. Now imagine seeing, beside one of those names, a carefully reconstructed face. The data stops feeling abstract. Suddenly, “aged 23, laborer, convicted of larceny” looks back at you with a crooked nose and a faint asymmetry in the jaw that might have made his smile slightly lopsided.

The convergence of osteology, digital modeling, and historical research has begun to knit together a more embodied archive. Where once researchers might talk broadly of “convicts” as a group, they can now trace particular individuals from skeletal remains to reconstructed faces, from burial grounds to archival records. A fragment of jawbone found in a forgotten grave might match the documented death of a named person at a specific settlement and, from that union of bone and ink, a life resurfaces.

Yet this is not only about satisfying historical curiosity. It’s about ethics too—about recognizing that these were people whose bodies were controlled, punished, and often discarded. Forensic reconstruction can, at its best, act as a kind of belated respect, a way of returning individuality to those who were long treated as expendable labor.

Listening to What the Skeleton Has to Say

Convict skeletons are not just skulls waiting for faces; they’re entire biographies etched into bone. Ribs bowed by childhood rickets, vertebrae compressed from hauling loads heavier than a human spine was meant to bear, healed fractures suggesting violence or accidents in harsh working conditions. Even teeth carry stories—grooves from pipe smoking, enamel defects from childhood hunger, accelerated wear from using teeth as tools.

When these skeletal clues are combined with forensic reconstruction methods, the result is a startlingly intimate view of convict life. A reconstructed face, for example, might show how an old broken nose subtly changed the set of someone’s eyes, giving them a permanent squint. Meanwhile, analysis of limb bones might reveal that this same person spent years engaged in grueling repetitive labor—swinging a pick, pushing a loaded cart, sawing timber for shipbuilding.

In this way, the new research phase confronts and complicates the simple narratives we sometimes tell about the convict past. The bones push back against clichés. They refuse to flatten into the tidy image of the “thief turned pioneer” or “criminal turned colonist.” The reality is messier, heavier, and much more human.

From Graveyard to Gallery Wall

Perhaps the most striking shift brought about by forensic reconstruction is where these stories now appear. Instead of being confined to academic journals or excavation reports, convict-era research increasingly finds its way into public exhibitions, museum galleries, and digital displays. Visitors step into dimly lit rooms and meet the gazes of reconstructed faces arrayed on the walls, each one linked to a sparse but powerful biography.

Some are labeled only with what is known—“Male, approximately 30, Irish origin suspected,” or “Female, late 20s, evidence of repeated pregnancies, cause of death unknown.” Others can be connected, tentatively but compellingly, to archival identities: a name, a ship, a crime deemed serious enough to justify transportation to the far side of the world.

These exhibitions change how we relate to the past. Instead of reading about “systemic brutality” in abstract terms, visitors see the healed fracture of a forearm that might have been raised instinctively to ward off a blow. They see dental disease etched into the smile of a reconstructed woman who likely lived with constant, gnawing pain. The story of the convict era lands not as distant history but as something felt in the body.

Balancing Truth, Respect, and Representation

With this new intimacy comes new responsibility. Reconstructing the faces of the dead is not a neutral act. It raises questions about consent, cultural protocols, and how the stories of marginalized or oppressed people are told. Many of the individuals being reconstructed today belonged to communities that were poor, politically powerless, or colonized. Some may have had descendants who carry their genes but not their stories.

Ethical research teams now work closely with descendant communities and, where relevant, with Indigenous groups whose lands once held convict burial grounds. Decisions about whether to display reconstructed faces, and how to frame their stories, are increasingly made in conversation rather than in isolation. Sometimes, the result is a quiet, private reconstruction used only for research; at other times, it is a public portrait accompanied by carefully chosen words that foreground dignity, not spectacle.

There is also the matter of uncertainty. Forensic reconstructions are estimations, not photographs. While skull anatomy guides the broad structure of a face, details like hairstyle, skin tone, and eye color often remain speculative. Responsible practitioners are transparent about this. They present reconstructions as informed visual hypotheses rather than definitive likenesses, adding nuance rather than claiming finality.

➡️ Nightlife venues are adjusting as sober socialising becomes a mainstream choice

➡️ Farmers are experimenting with regenerative grazing to rebuild soil after decades of depletion

➡️ Ocean chemistry data is pointing to faster acidification along sensitive marine habitats

➡️ Fashion labels are returning to wool as demand grows for durable climate smart fabrics

➡️ Archaeologists are returning to old shipwreck sites with new imaging technology

➡️ Households are embracing minimalism as rising costs challenge traditional consumer habits

➡️ Space startups are expanding beyond satellites as deep tech exports gain momentum

A New Kind of Archive Emerges

What is taking shape, slowly and delicately, is a hybrid archive of the convict era—one part bone, one part pixel, one part ink on paper. Researchers cross-reference skeletal analysis with ship manifests, hospital ledgers, muster rolls, and court documents. Forensic databases, once designed for modern identification, now help decode the physical stresses of 19th-century penal labor.

To make sense of this emerging complexity, some teams use simple tables and digital dashboards—an echo of the old ledger books, but with a new, embodied twist. A reconstructed individual might be summarized like this:

| Feature | Observation |

|---|---|

| Approx. Age at Death | 32–36 years |

| Biological Sex | Male |

| Skeletal Evidence of Labor | Pronounced muscle attachments in upper limbs; spinal compression |

| Health Indicators | Healed rib fractures; dental caries; signs of malnutrition in early life |

| Reconstruction Status | 3D facial approximation completed; displayed with contextual biography |

In earlier generations, this person might have appeared in the record as nothing more than a fleeting mention: “Dead, cause unknown.” Today, their life is pieced together from the weight of their bones, the traces of their labor, and a face carefully shaped from digital clay.

Standing Face to Face With the Convict Past

There is a quiet moment that happens often in these projects, though it rarely appears in the reports. It usually comes late at night or at the tail end of a long day, when the last edits to a digital reconstruction are done. The screen shows a face in three-quarter view, light rendered softly across cheek and brow. The researcher leans back, eyes lingering on the image, and for a heartbeat or two the distance of centuries collapses.

In that fleeting pause, the convict era stops being an era at all. It becomes a collection of people: those who stole because they were starving, those who resisted authority and were crushed for it, those who were swept up in the machinery of empire. People with headaches and jokes, with favorite foods and private fears, with habits of frowning or squinting into the sun.

Forensic reconstruction doesn’t redeem the brutalities of transportation and forced labor; it doesn’t excuse or undo. But it does insist that we meet the past eye to eye. It challenges us to remember that the building of colonies was paid for not just in years of imprisonment, but in bones, in broken spines, in teeth worn down to dark stumps. And that, alongside the pain, there were also friendships, small acts of kindness, and stubborn streaks of survival.

Convict-era research has entered a new phase, one in which the archive is no longer only a place of paper and ink, but also a space of faces and bodies. In cool labs and dim museum halls, the transported dead are returning—not as ghosts, but as carefully, respectfully reconstructed human beings. As we learn to look back at them, they teach us to ask different questions about justice, punishment, and what it means to be remembered.

FAQ

Are forensic facial reconstructions exact portraits?

No. They are informed approximations based on skull anatomy, tissue-depth data, and forensic standards. They capture likely structure and proportion, but details like hairstyle, some soft-tissue features, and exact expression remain uncertain.

How do researchers know which remains belong to convicts?

They combine archaeological context (location and burial patterns), osteological analysis, and historical records such as burial registers, hospital logs, and site maps. In some cases, inscriptions or artifacts strengthen the association.

Is this kind of work respectful to the dead?

Ethical projects involve consultation with descendant and local communities, follow cultural protocols where applicable, and emphasize dignity, transparency, and educational value over sensationalism.

Can DNA help identify individual convicts?

Sometimes. DNA analysis can reveal ancestry, biological sex, and disease markers, and may occasionally connect remains to living relatives. However, preservation, contamination, and incomplete historical records often limit specific identifications.

Why does giving convicts faces matter today?

Seeing individualized faces challenges stereotypes and abstractions. It restores a measure of personhood to people long treated as disposable, deepens public understanding of penal history, and prompts reflection on how modern societies treat those they punish.