The first time you hear it, the phrase sounds like something from late-night sci‑fi: the United Kingdom is building a monster designed to twist plasma in every direction. Not a creature exactly, but a machine—vast, humming, and almost alive in the way it bends the rules of physics. It’s called MAST Upgrade, a new kind of fusion experiment, and somewhere on the other side of the world, in a quiet corner of Oxfordshire, it’s learning to tame a tiny artificial star.

A Star in a Shed (Well, Sort Of)

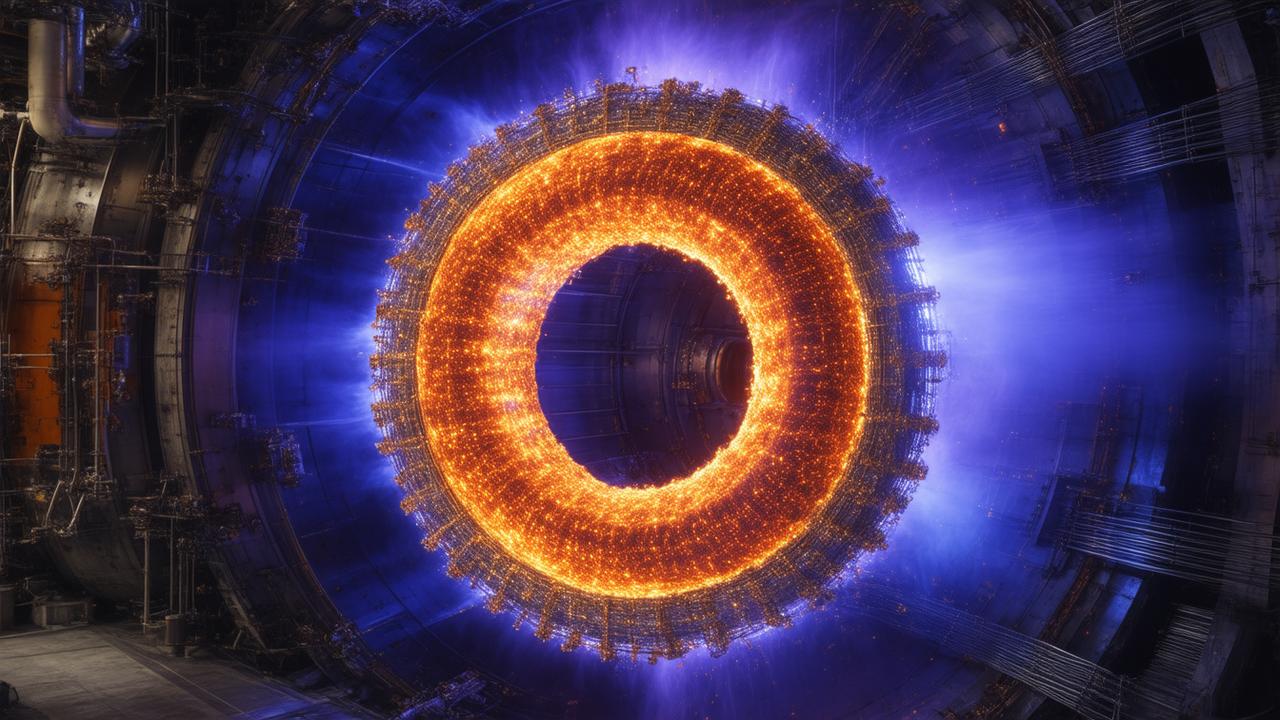

Imagine walking through a drizzly English morning, past brick buildings and clipped lawns, and then stepping into a hall that feels like the inside of a science-fiction prop. There’s a smell of clean metal and coolant, the low thrum of pumps, the soft hiss of vacuum lines. In the centre of it all sits something that looks like a mechanical heart designed by a very determined octopus—tubes, cables, magnets, scaffolding rising in every direction.

This is MAST Upgrade, the UK’s flagship “spherical tokamak,” a kind of fusion reactor that doesn’t look like the classic doughnut you might have seen in textbooks. Instead, it’s more like an apple core: compact, bulbous, and wrapped in powerful magnets designed to twist plasma—superheated, electrically charged gas—into a tight, tense loop.

To run, MAST Upgrade has to heat hydrogen gas until it becomes hotter than the centre of the Sun. At those temperatures, electrons strip away, nuclei lose their shyness, and fusion—the fusing of light atoms into heavier ones—becomes possible. Each fusion reaction releases a burst of energy. String together enough of those reactions, and you don’t just have a science experiment. You have a power source that could change the way we live on this planet.

For Australians watching from across the globe, this might sound distant and abstract. But the stakes—climate, energy security, and the future of our grid—could not be closer to home.

The Monster That Twists Plasma

At its core, fusion is simple: push atoms together so hard that they merge and release energy. In practice, it’s like trying to hold lightning in a woven basket made of magnetism. Plasma is wild. It wriggles, it roils, it slams into the walls of any container you give it—unless that container is made of invisible, carefully sculpted magnetic fields.

The UK’s “monster” is designed specifically to twist plasma in every direction, to shepherd it away from the walls and into a steady, controlled dance. In a traditional tokamak, you have a ring-shaped vessel and magnets that force the plasma to loop around in a torus, like a racetrack. In a spherical tokamak like MAST Upgrade, the racetrack is squashed inward. The plasma becomes more tightly wrapped, the magnetic field lines more efficient, the whole configuration looking less like a tyre and more like a rugby ball.

To a physicist, that change in shape is everything. The spherical design can potentially achieve the same performance as larger, conventional machines but in a smaller, cheaper package. Think of it as a compact 4WD that somehow tows like a road train. If it works the way scientists hope, it could drastically shrink the size and cost of future fusion power plants.

Inside MAST Upgrade, superconducting magnets create colossal magnetic fields, while powerful beams of particles and microwaves slam into the plasma, heating it to hundreds of millions of degrees. Sensors line the vessel, capturing the behaviour of the plasma in exquisite detail. The machine is not just trying to make fusion happen—it’s trying to understand, at a deep level, how plasma behaves when it’s pushed to its limits.

Why Australians Should Care About a Reactor in Oxfordshire

Fusion has always been a global pursuit—too complex, too expensive, and too important for any one country to tackle alone. For Australia, perched between bushfire seasons and bleaching reefs, the stakes could not be clearer. We live on a continent where the climate story is written in smoke, saltwater, and heatwaves heavy with the whine of air conditioners.

Right now, our energy conversation is dominated by solar, wind, gas, and coal, with storage and grid stability as the big headaches. We’re a world leader in rooftop solar, yet we still wrestle with how to keep the lights on when the sun shuts off and the wind dies down. Fusion doesn’t replace renewables—it complements them. It’s the dream of always-on, low-carbon power that can sit in the background, steady and quiet, like a reliable base note in a song full of highs and lows.

The UK’s work on MAST Upgrade isn’t just an interesting science story; it’s part of a race that Australia has quietly joined. Australian researchers contribute to international fusion projects, our universities model plasma behaviour, and our companies explore advanced materials and technologies that reactors will one day need. While we don’t yet host a flagship tokamak like MAST, we’re woven into the same global network of experiments, simulations, and shared data.

When the UK learns to better handle plasma instabilities—those unhelpful wriggles and eruptions that can stop a fusion reaction in its tracks—Australian scientists read the papers, test the models, and feed those lessons into their own work. When new designs emerge for divertors—the exhaust systems that handle the intense heat and particles escaping the plasma—it’s not just British engineers who take note. It’s everyone planning for a future where fusion plants sit alongside solar farms and battery banks, from Cornwall to the Pilbara.

The Art of Controlling a Tiny Sun

If the heart of fusion is physics, the soul of it is control. MAST Upgrade is less like a simple heater and more like an orchestral conductor for charged particles. Every tweak of a magnetic field, every pulse of power, every diagnostic snapshot is part of a huge, coordinated effort to keep the plasma balanced between chaos and collapse.

In practical terms, the UK team is obsessing over a few crucial challenges that matter to everyone—Australia included:

- Keeping the plasma stable: Just like the atmosphere forms storms, plasma forms swirls and eddies that can knock the system out of tune. Learning to calm those storms is vital.

- Handling the exhaust: Fusion reactions create helium “ash” and an enormous heat load where magnetic field lines strike the walls. MAST Upgrade is designed to test new ways of spreading and cooling that heat so future reactors don’t melt from the inside out.

- Maximising efficiency: It’s not enough to make fusion energy; you have to make more than you spend in heating, magnets, and control systems. Spherical tokamaks might help tip that balance in our favour.

Australian engineers and policy makers are watching these questions closely. Any pathway that makes fusion smaller, cheaper, and more manageable is a pathway that makes it easier to deploy in countries with long coastlines, sparse populations, and grids that stretch across deserts and mountains. A compact fusion plant tucked near an industrial hub in Western Australia, or feeding a remote mining operation, suddenly doesn’t feel entirely far-fetched.

How Fusion Stacks Up for Australia

To see where this might fit in our energy mix, it helps to line fusion up against what we already know:

| Energy Source | Key Strength for Australia | Main Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Solar | Abundant, cheap, perfect for rooftops and remote sites. | Intermittent; needs storage and grid upgrades. |

| Wind | Strong coastal and inland wind resources. | Variable output and local opposition in some regions. |

| Fossil Fuels | Existing infrastructure, dispatchable power. | High emissions, climate and policy pressure. |

| Fusion (Future) | Low-carbon, always-on, small land footprint. | Still experimental; commercial deployment decades away. |

In a country like Australia, where sunlight and wind are already claiming a big share of the grid, fusion’s real value may come later—when we’ve pushed renewables as far as we can and still need a firm, clean backbone of power that doesn’t depend on weather patterns or imported fuels.

Listening for the First Real Roar

In the control room of MAST Upgrade, there’s no dramatic switch that suddenly lights up London. There are, instead, shots. Each “shot” is a brief pulse of plasma—milliseconds to seconds long—cradled in magnetic fields while hundreds of instruments watch.

When the machine runs, displays flicker with coloured lines, cameras capture the flick of plasma against invisible cages of magnetism, and teams lean in to see if the last tweak improved things even slightly. Did the plasma stay stable a little longer? Did the heat distribution look smoother? Did an instability appear where the models said it might—and did the control systems catch it in time?

➡️ The streak-free window-cleaning method that still works flawlessly even in freezing temperatures

➡️ The quick and effective method to restore your TV screen to like-new condition

➡️ Thousands of passengers stranded in USA as Delta, American, JetBlue, Spirit and others cancel 470 and delay 4,946 flights, disrupting Atlanta, Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, Dallas, Miami, Orlando, Boston, Detroit, Fort Lauderdale and more

➡️ The sleep pattern that predicts alzheimer’s risk 15 years before symptoms

➡️ These zodiac signs are destined for major prosperity in 2026, according to astrological forecasts

➡️ The RSPCA urges anyone with robins in their garden to put out this simple kitchen staple to help birds cope right now

➡️ The RSPCA urges anyone with robins in their garden to put out this simple kitchen staple today

It’s fussy, patient work. But every shot is a rehearsal for a future where machines like this don’t sit in research labs but behind high fences on the edge of cities, feeding gigawatts of power into grids like the National Electricity Market here in Australia. One day, the data from MAST Upgrade might inform the design of a reactor commissioned by a state government in Queensland, or a private energy consortium in South Australia.

For now, Australians can think of the UK’s plasma-twisting monster as a kind of distant relative to our own energy experiments—a cousin tinkering away in a cold shed, sending letters home that we quietly fold into our plans. As the years tick by, those letters start to spell out not just scientific insights, but the earliest engineering blueprints for a technology that could define the second half of this century.

From Science Fiction to Shared Future

There’s a particular kind of Australian twilight where this all feels especially real. You might be standing on a verandah watching the last heat bleed out of a 40-degree day, cicadas tuning up in the gum trees, the sky turning from peach to black. Power lines hum softly overhead. Somewhere, a coal station is still burning through tonnes of rock; somewhere else, a battery is quietly discharging the day’s sun back into the grid.

In that moment, the idea of a machine that makes energy from the same process that lights the stars doesn’t feel like fantasy. It feels like something we might one day simply expect—like turning a tap and trusting water to flow.

The United Kingdom’s decision to build a reactor designed to twist plasma in every direction isn’t just a technical curiosity. It’s one of many necessary steps in a global experiment to see whether we can learn to hold a star, not in the palm of our hand, but within the thin shell of a steel vessel wrapped in magnets and hope.

Australians are already living on the front line of climate change. We know, in our bones and on our skin, that the old energy story can’t go on as it has. Fusion won’t arrive in time to solve every problem. It won’t replace the urgent need to decarbonise now, with the tools we already have. But as MAST Upgrade hums and crackles in that English hall, it points toward a future chapter of our energy story—one where our grandchildren might look back at coal not as a contested political symbol, but as a curious relic.

And when they ask how we got there, the answer will stretch across oceans: from wind farms off the Tasman Sea to solar panels on Brisbane roofs, from supercomputers in Sydney to a spherical tokamak in Oxfordshire that learned, slowly and stubbornly, how to twist plasma into submission.

FAQ

What exactly is fusion energy?

Fusion energy comes from fusing light atomic nuclei—typically forms of hydrogen—into heavier nuclei, releasing large amounts of energy. It’s the process that powers stars, including our Sun, and it produces far less long-lived radioactive waste than current nuclear fission reactors.

What is a spherical tokamak like MAST Upgrade?

A spherical tokamak is a type of fusion reactor where the plasma is confined in a compact, almost spherical shape rather than a wide doughnut. This geometry can make magnetic confinement more efficient, potentially allowing smaller, cheaper reactors compared with traditional designs.

How could fusion benefit Australia specifically?

Fusion could provide steady, low-carbon power to complement Australia’s solar and wind resources. In the long term, it could support energy-intensive industries, remote communities, and large-scale hydrogen production without relying on fossil fuels.

Is fusion a replacement for renewables like solar and wind?

No. Fusion is better seen as a partner to renewables, providing firm, always-on power when sun and wind are low. The immediate priority remains rapidly scaling up renewables and storage, with fusion as a potential long-term addition to the energy mix.

When might fusion power become commercially available?

Most experts suggest that commercial fusion power plants are unlikely before the 2030s or 2040s, and widespread deployment will take longer. Experiments like MAST Upgrade are crucial steps toward proving that fusion can be practical, reliable, and economically viable.

Is Australia involved in fusion research?

Yes. Australia participates in international fusion projects, conducts plasma physics research at universities, and contributes through modelling, diagnostics, and advanced materials research. While we don’t host large tokamaks like MAST Upgrade, we’re part of the global effort to make fusion a reality.